The Panoramas: Rewriting History

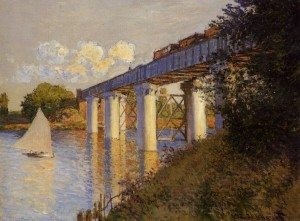

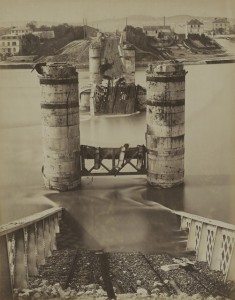

Representing history in France had always been fraught with difficulty for centuries. Not until the Third Republic (1870-1940) was it possible to report, write or make art without the threatening overhang of censorship, but, after the Franco-Prussian War, the cultural producers felt the heavy hand of social responsibility on their collective shoulders. After the Germans had determined the best way to collectively punish the French, how best to crush the spirit of the nation, it was up to the artists to depict to the new nation its fresh republican face. Although, for the most part, the avant-garde artists opted out of this post-war task, one occasionally sees a possible whiff of patriotism in Impressionist works in the wake of the war. The painter landscape painter, Claude Monet (1840-1926), returned from London where he waited out the short war and settled in the suburban village of Argenteuil, already in recovery mode by 1872. As they closed in on Paris during the final siege, the Prussians had destroyed the two old bridges that crossed the Seine, but as though to wipe out old wounds, a new iron structures, bright and shiny and modern, had defiantly sprang up. As Christoph Heinrich pointed out in Monet (2000), the two bridges were very different. The old wooden bridge was replaced with “cast iron girders, but in the reconstruction considerable emphasis was placed on giving these a decorative air, as if wrought by a craftsman’s hand. The other bridge was a railway bridge; and both its function and the concrete and precast iron parts of which it was built made it highly modern.” Monet painted the triumphal bridge seven times.

Claude Monet. The Railway Bridge at Argenteuil (1873)

Destroyed Bridge at Argenteuil, 1870

While it would be a bit harsh to call an individual who was unwilling to support what was a war among rulers and empire builders as being “unpatriotic,” Monet did not participate in the war, while many of his friends did join in active combat. In his 2004 book, Impressionism: Paint and Politics, art historian John House writing of the Impressionists and their work immediately after the Franco-Prussian War stated, “Little evidence survives of a direct linkage between their choice of subjects and the pressures of the market in these years..” but as was stated in the previous posts on military painting, after the war, there was a huge and expansive visual and literary project devoted to celebrating French bravery and heroism against the Prussians. The repeated depiction of such a famous bridge, even by a renegade Impressionist, would have attracted an audience sympathetic to the content of the painting–French renewal–if not to the style of painting a notable example of rebuilding. Indeed, if one tracks Impressionism and Post-Impressionist content and subject matter (not style) with that of the academic salons, there was, for decades, a striking similarity in themes that is often overlooked in the drive to separate the avant-garde from the academy. While the local press did not care for the railway bridge at Argenteuil, writing “Instead of an elegant construction of grandiose form there is only a heavy and primitive work which is not at the level of progress, they made a wall of iron impenetrable to the eye …the bridge should be embellished with carved capitals and some cast-iron decorations to break up this relentless straight line with the taste that so gloriously characterizes our nation,” the rebuilding project signified recovery and redemption, even if it was too modern for some tastes.

For the sake of argument, it is provocative and hopefully illuminating to place the bridges of Impressionist artists–Claude Monet and his bridge and Camille Pissarro and his factories–next to the vast panoramic recreations of the last stands of the heroic French Army by history painters Édouard Detaille and Alphonse de Neuville and see both bodies of post-war work as part of the vast discourse of post-war healing and renewal. There was much work to be done. While the Impressionists dabbled at the edges of national soothing, it was the military painters who, as was pointed out in previous posts, bore the main burden of redeeming the honor of the French nation in the eyes of the broader Parisian public. It is necessary to pause to make a distinction between “Paris” and the rest of “France, between the “Empire” and the “nation.” For the entire modern history of France, from the French Revolution to the Third Republic, the term “nation” was an ambivalent one: on one hand the post-monarchial governments understood that authority stemmed from Paris but on the other hand, the rest of France was not Paris, did not consider itself “French,” and, in many regions, did not speak French. After off and on attempts to unite France, frequently through military conscription, it was the Third Republic that began to seriously work on a universal educational curriculum, which aimed at eradicating regional identities for a national identity, which was “French,” i. e. Parisian, an effort that was deeply resented by its reluctant recipients.

This political sleight of hand was on view when the Emperor cravenly surrendered at Sedan. The new Republic promptly repudiated the conflict, claiming that the war was his and his alone and attempted to negotiate with Prussia by claiming innocence in the entire mad enterprise of the Second Empire, which did not concern “France” itself. The Prussians did not quite see the elegant logic of the argument and imposed demands upon the entire nation–the same reparations it was asked to pay when the first Napoléon had conquered Prussia, the sacrifice of the borderlands of Alsace and Lorraine–forcing all the French to make amends for what was actually a lapse of judgment on the part of the Emperor that took place in Paris. And it was Paris and its people who refused to bend to Prussian demands and fought on for months and endured a siege before bowing to the inevitable defeat. The mood of the nation during that année terrible was poetically expressed in overwrought tones by Victor Hugo’s (1802-1885) poems written during the Siege and its aftermath, surrender and defeat. In his poem Before the Conclusion of the Treaty, certain stanzas stand out:

“If this foul war we ended see/And grant all Prussia longs to get/Then, like a glass our France would be/Upon a pothouse table set–You empty it, and then you break!/Our haughty country is no more/O grief, that shame should overtake/Where only honor lived of yore!/Black morrow, with dismay for text;/All dregs we doing–on ashes feed;/The eagles gone; there follow next the vultures, those do hawks succeed./Two provinces now torn away–Metz poisoned, Strasburg crucified;/Sedan, deserter in the fray,/A brand on France that will abide./There lives in souls degenerate/Base love of loathly happiness–/Pride cast away; they cultivate/The growth, the increase of disgrace./Our ancient splendor stained, belied,/Our mighty wars dishonored now,/The country mazed and stupefied,/Unused to live with lowered brow…”

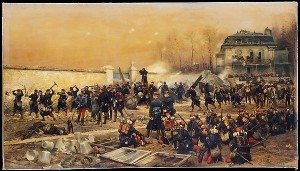

Two pupils of Ernest Meissonier (1815-1891), Édouard Detaille (1848-1912) and Alphonse de Neuville (1835-1885), teamed up to paint two huge panoramic vistas of two fierce battles, one fought hand to hand house to house at the very doorstep of Paris, near the Marne, the other full of flash and dash and bad leadership on the part of the French generals. These battles, Champigny and Rezonville, were celebrated memories, not because they ended well–the defeated French either surrendered or retreated into the city of Paris–but because these skirmishes were the last desperate struggles of a valiant and outnumbered French army, or what was left of it, fighting for honor, not glory. The first panoramic production featured the dramatic fighting at Champigny in the vicinity of the Marne and was put on display in 1882. Its immense popularity inspired a second effort, this one featuring the pitched battle in the vicinity of Rezonville, outside of Metz. This 1885 production was the last major work for Neuville, who died that year.

Fragment from the Battle of Rezonville

These days-long battles were among the last of traditional set pieces of Napoléonic style warfare with calvary charges over green and open fields–galloping horses ridden by dashing officers in splendid uniforms–colliding with modern military facts. Indeed, the encounters between French and Prussian calvaries on at least two occasions were noteworthy for its futility, bloodshed, misplaced medieval gallantry in the face of mechanized weaponry. In their own ways, both battles had elements that, with hindsight, can be understood as warnings for the future–events that would repeat in the next century, especially last stands at the Marne and insane gallops into hails of bullets.

Catalogue for Panorama for the Battle of Rezonville

The Panorama of the Battle of Champigny opened at the Panorama National opened in November, 1882 to great acclaim. The panorama, located at 5 rue de Berri, was a tremendous success, attracting a German visitor, who remarked ruefully,

“How typical of the French to want the whole acton to be represented with a pomp and boastfulness that is so Fench. Wherever you look, the French are victors–see, here they are taking prisoners, there they’re about to capture a whole group of Germans..Despite the obvious weakness of of the composition, the Panorama of Champigny deserves a place of honor alongside the best that has been produced over the past few years. The relation between the painting and the actual objects has been handled with much finesse and rendered most realistically, so much so that he optical illusion works wonderfully well.”

Author of The Panorama (2003), Bernard Comment, who found the quotation, noted that “During the first four months, takings for the Battle of Champigny were 400,000 francs. The cost of entry was two francs, and attendance averaged out around sixteen hundred visitors a day.” The Franco-Prussian War had ended (badly) a decade ago, but the French audience clearly still needed comforting.

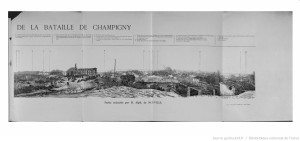

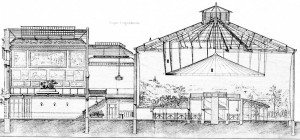

Panorama National at the Rue de Berri

The two artists followed the methods learned from Meissonier, precision and accuracy as appropriate to history painting, still the best way to illustrate contemporary events in all the color and complexity. Although Detaille had been present during the defense of Paris, he joined Neuville at the sites where the battle had taken place. Dividing the territory between them, the artists made detailed sketches, worked up more precise studies, and then took photographs of the final version of each section. Neuville was in charge of the overall composition, while Detaille created various small incidents and scenes, bits of action among the soldiers to place in the wide terrain.

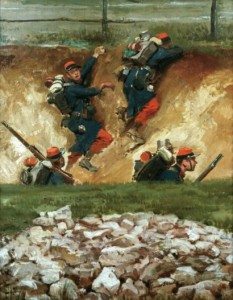

Alphonse de Neuville. Battlefield of Champigny

Unlike Meissonier, who preferred a high point of excitement and military drama and favored hallowed heroes, Detaille, who came from a military family, focused on individual soldiers, ordinary men who rose to the occasion and performed small heroic deeds in desperate combat. This intimate approach from Detaille was possibly the correct one for a war that had been lost. The French public were shocked at the defeat of its Army at Metz and Sedan and as Wolfgang Schivelbusch pointed out in his very interesting 2004 book, The Culture of Defeat: On National Trauma, Mourning, and Recovery, that “The news of France’s crushing defeat produced an astonishing capacity among the citizenry to invent an alternate, more comforting reality.Within hours, before the national malaise could set in, the revolutionary past was being reenacted..Once again, only Napoléon had been defeated, not the nation, and the shame of Sedan disappeared with him into a German prison. The revolution, on the other hand, and the republic it created were the guarantors of ultimate victory. Of that everyone was certain.”

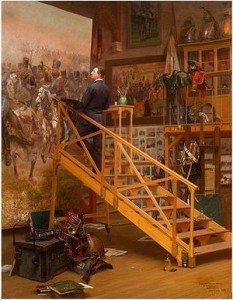

Basile Lemeunier. Detaille Painting the Battle of Champigny

The 1896 book, Battles of the Nineteenth Century, presented an account of the Battle of Champigny, which attested the to English interest in French history. “The Great Sortie From Paris: Champigny: Nov. 29. Dec. 2, 1870” by A. Hilliard Atteridge reported, “It was in the second month of the siege of Paris..The iron ring of the German siege works cut off the city so effectually from the rest of France..The newspapers all called for a grand sortie agains the German lines.” Atteridge described the sortie and the maneuverings of the two armies at great lengths, discussing what was essentially street to street fighting in the villages of Brie and Champigny on the first of December: “But in the broken ground, and among the numerous enclosures along the front to the two armies, the battle was mainly an infantry fight. Three times during the eight hours that the battle lasted the villages were taken and retaken, remaining at the close of the day still in the hands of the French. In Champigny, the fighting was close and desperate–from house to house, from barricade to barricade.” The aim of the sortie was to break free of the German encirclement around Paris, but as Atteridge noted. “Thus the French had held their own when attacked, and though they claimed the days as a victory, the main advantage was with the Germans. The great sortie had failed.” And as the author noted, “The Germans did nothing to disturb the retreat.”

The days long struggle to break the German lines as described by Atteridge were the basis for the scenes depicted by the artists ten years later. From the scenes that have survived from the panorama, it is possible to state that the many tableaux seem to be very close illustrations of the numerous small and intense actions that made up the entirety of the failed sortie. The multiple sections, combining Detaille’s actions inside of Neuville’s panoramic design, were then projected, by magic lantern, onto the canvas which was stretched along the long wall of the panorama building. Working like Renaissance masters, the military painters took responsibility for the hundreds of figures, while their assistants painted the backgrounds and the skies.

Fragment from Panorama of Battle of Champigny

The fifty foot high and four hundred feet long painted canvas weighed two tons and, when mounted on the wall was “read” and viewed by visitors who walked along a raised platform. Each visitor had a guide book and could follow the various points of interest and vicariously participate in the combat. It must be assumed that most of the visitors were in Paris during the Siege, remembered the starvation and the siege guns battering the city. The only place the painting could be displayed in its totality was in the building that was constructed for this purpose, but even though panoramas precursors to films, cinema, they were expensive to maintain and the fad for such paintings passed. The Battle of Champigny was cut into many pieces over a period of four years, between 1892-1896, and distributed to a variety of collectors. In 2012, Sotheby’s offered some forty fragments for sale, and a preliminary painting of The Battle of Champigny is owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, far from Paris, where this military panorama had once meant so much.

Édouard Detaille. The Defense of Champigny (1879)

The companion piece or the successor to Battle of Champigny was the Battle of Rezonville, also dismembered, cut into one hundred fifteen sections. As the 1896 issue of The Quartier Latin, Volume 1 reported in a brief note, “After having been exhibited in all the large cities of Europe, the cyclorama painting by Edouard Detaile and the late Alphonse de Neuville, illustrating the battle of Rezonville, has been cut into morceaux, and even into small easel pictures, and sold.At the same time the fragments of the companion picture, the battle of Champigny, by the same artists, were also sold.”

Fragment from the Battle of Rezonville

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.