IMPRESSIONISM, FASHION, AND MODERNITY

Musée d’Orsay, Paris, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Art Institute of Chicago

September 2012-September 2013

Part Two: The Codes of Fashion

Fashion and Gender

Like the century itself, Parisian fashion was hybrid and Janus-faced, old and new, hand and machine made, available for middle and upper classes, from prêt-à-porter to haute couture. In its hybridity and complexity, fashion exemplified all that was modern—the shift from old to new, caught in a moment of transformation. In Realist and Salon painting, fashion was a man’s game, seen through the eyes of men. The very small number of paintings by women featured in the Metropolitan exhibition testifies to the extent that women as artists were virtually excluded from the ranks of the great painters of women’s fashions. This relative absence of women as painters of fashions was paralleled by a similar lack of women who wrote realist novels of manners with a strange gap between Jane Austen (1775-1817) and Edith Wharton (1862-1937), which was filled in with Balzac and Flaubert. It is difficult to know if the absence of all but a few paintings by women—Berthe Morisot (1841-1895), Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), Eva Gonzalès (1849-1883)—reflects the small number of female Realist artists or the difficulty of obtaining works by these artists for the exhibition. But it is clear that the nineteenth century male artists were fascinated by women’s clothes, from underwear to outerwear, while women seemed to have very little interest in men or their clothes. Like men, women were interested in the world of women.

Men’s Fashions

The world of women was dominated by fashion. Forced by custom to change costumes several times a day, women were entertained by elaborate clothes which substituted for the political rights and economic opportunities denied. For men, their outfits served a precisely opposite function–their costumes were performances of politics and class in the “reality” that was Paris and the life of the upper class male flâneur who was a spectator and participant in the metamorphosis of the century. Unlike women who merely wore the clothes, men could actually participate in a life of luxury and leisure and spectatorship. Women were confined and contained and watched for details of deportment, from dress to facial expressions to bodily postures and positions. They were allowed to venture out of their abodes alone and could walk in the streets alone, a real ordeal, given their costumes, provided they “kept moving” and had shopping as their main goal. From the moment that the grands magasins began to open with the Bon Marché in 1863, women were constructed as consumers of ever-changing fashion and themes of desire began to emerge on the alluring stage of the department stores: desire is manufactured, desire for things—dresses, hats, gloves, fans—although artificial, desire could be fulfilled simply by purchasing something, no matter how small—a piece of trimming, a new set of buttons. It was easy to be diverted by shopping. Never have women’s clothes been so lovely or so huge or such a feast for the eyes or so uncomfortable or so complicated. Brigit Haase described the astonishing procedures for simply lifting a skirt made from “fourteen panels of cloth cut diagonally on one side:”

The considerable quantity of material could be gathered by the wearer according to her preference by means of an arrangement of strings. To this purpose, long, narrow ribbons—called tirettes (literally, “little pulls”) or pages—were attached to the skirt’s inside along all vertical seams; their upper ends were tied to buttons loosely fastened above small openings in front and back of the waistline. Pulling the buttons raised the skirt’s hem.

In contrast to the intricate machinery of female attire, the clothing of men of all classes simplified and became a “democratic” uniform that nevertheless worked to mark off one class from another.

Gown by Charles Frederick Worth

Certainly after the failure of the Revolution of 1848, it was compensatory for men to compete over the cut of their redingote rather than over when to start the next uprising. Men disappeared into a dark uniform of “funeral” blackness, differentiated by tailoring details and accessories: the cane, the gloves, the collars and cuffs and the tall hat. The lack of color, the lack of embellishment for the male was a gesture of political solidarity of the bourgeoisie against any lingering sentiment for the hereditary monarchy. But by the Second Empire, the male suit was more a matter of tailoring rather than a matter of class equality.

For the male, fashion as worn by the man about town was a serious business, linked to the subtleties of rank, privilege and wealth. As Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) pointed out in his essays for the Salon of 1846, after the preceding century of colorful clothing, the bourgeois male was inflicted with his own uniform, the habit noir, or the black suit. As Baudelaire wrote,

As for the garb, the outer husk, of the modern hero, al- though the time is past when every Httle artist dressed up as a grand panjandrum and smoked pipes as long as duck rifles, nevertheless the studios and the world at large are still full of people who would like to poeticize Antony with a Greek cloak and a parti-coloured vesture. But all the same, has not this much-abused garb its own beauty and its native charm? Is it not the necessary garb of our suffering age, which wears the symbol of a perpetual mourning even upon its thin black shoulders? Note, too, that the dress-coat and the frock-coat not only possess their political beauty, which is an expression of universal equality, but also their poetic beauty, which is an expression of the public soul— an immense cortege of undertaker’s mutes (mutes in love, political mutes, bourgeois mutes.. We are each of us celebrating some funeral. A uniform livery of affliction bears witness to equality; and as for the eccentrics, whose violent and contrasting colours used easily to betray them to the eye, today they are satisfied with slight nuances in design in cut, much more than in colour. Look at those grinning creases which play like serpents around mortified flesh— have they not their own mysterious grace?

This essay on the “Heroism of Modern Life” was a plea from Baudelaire to artists who lived in a modern age in which heroism was the daily condition in a large city jostling with competition and class. There were men of old money, men of new money, men of no money, men of letters, poseurs and performers–each category had its own garb and costume. Clothing, for the male, was a powerful signal. The uniform, black frock coat, black shiny top hat, discrete cane, blindingly white linen at the throat and wrists, were indeed superficially similar but in the minute details of tailoring, a tale of status could be discerned.

No one wore clothes better than the painter Édouard Manet (1832-1883), who used his formal and elegant 1867 portrait (Édouard Manet) by Henri Fantin-Latour (1836-1904) to convince his artistic detractors and his Salon rivals of his moral worth as a gentleman. In fact, the subtle signals in this portrait remind the viewer-in-the-know of the fact that Manet’s family owned vast tracts of land in the suburbs outside of Paris. Clearly, Manet who did not have to work for a living, was a sincere and dedicated artist worthy of respect for his dedication to his craft and his vocation.

Henri Fantin-Latour’s Portrait of Manet

Given that tastes for male beauty have changed so much since the nineteenth century, it is difficult for us to judge Manet’s handsomeness but, for the young artist, George Moore, there was no doubt. His reaction to Manet was nothing short of rapturous:

Although essentially Parisian by his birth and by his art, he had in his physiognomy and his manners something that made him resemble an Englishman. Perhaps it was his clothes—his outfits with their elegant cut—and his way of carrying himself! His way of carrying himself!…those square shoulders swinging from side to side when he crossed the room, and his slender waist, and that face, that nose, that mouth.

Then as now, male clothing required a trim and slim body to wear with the appropriate panache. Figure flaws, short legs and large paunch, were hard to hide; and male fashion was best worn by young men with slim waists, long legs, and money. Frédéric Bazille’s (1841-1870) Family Reunion (1867) exemplified the new style of portraiture, the ensemble, showed young and prosperous men and lovely and well-dressed women enjoying each other in an open-air setting. Although Bazillle foregrounds the women and their costumes, the men perform their upper middle class status. They pose casually and exude confidence: one seated male crosses one leg languidly over the other—a position forbidden to women, while the other males stand, almost at attention, showing off their white summer trousers and matching white vests and shirts, set off by the standard black frock coat.

Frédéric Bazille. Family Reunion (1867)

Édouard Manet was the epitome of the haute bourgeoisie who had inherited the earth, money and power and social status. He would be one of the last of his class to venture into fine art and his Impressionist cohorts and outsider artists, such as Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Pierre Renoir (1841-1919) could not keep up with the sartorial splendor of Bazille and Gustave Caillebotte (1848-1894), men of his own class. Bazille, who died in the Franco-Prussian War, did not live to fulfill the promise of his talent , actually relied on his mother to buy his clothes. Coming from petite bourgeois backgrounds, Monet and Renoir often used female models (wives and mistresses) to act out their social aspirations to rise into the middle class. Middle class women could emulate haute couture fashion through department store clothing and Impressionist paintings of the Second Empire show women carefully posed in the manner of fashion plates, displaying their aspirational costumes. Bazille’s portrait of Renoir (Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1867) shows the young and uncertain artist in his bourgeois suit with somewhat baggy pants with his knees pulled up to his chest, in yet another pose of male freedom that would never be allowed to a woman, even a young girl. One could argue that a truly upper class male would never sit in such a posture that is so inelegant, so uncaring of the proper fit of the clothing and yet such casualness came naturally to Renoir, who was from the lower classes.

Bazille’s portrait of Renoir

Indeed upper class males had their own attitudes of privilege and poise and some of these paintings reveal the psychology of the unconscious advantages of their class. One would never see an upperclass male with his knees drawn up and his feet on the furniture. Upper class men posed to show themselves off to their best advantage. James Tissot’s (1836-1902) The Circle of Rue Royale (1868) displays a group of men with prerogatives displaying themselves to each other on the neo-classical pavilion of the Gabriel balcony of the Jockey Club. Located in the Hôtel Scribe at this time, the Jockey Club was dedicated, as it said, to “the improvement of horse breeding in France.” According to the Musée d’Orsay, the scene is set on “one of the balconies of the Hôtel de Coislin” and it should be noted that each languid aristocrat is a portrait of actual pedigreed males: the Comte Alfred de la Tour-Maubourg (1834-1891) the Marquis Alfred du Lau d’Allemans (1833-1919), the Comte Étienne de Ganay (1833-1903), the Capitaine Coleraine Vansittart (1833-1886), the Marquis René de Miramon (1835-1882), the Comte Julien de Rochechouart (1828-1897), the Baron Rodolphe Hottinguer (1835-1920), the Marquis Charles-Alexandre de Ganay (1803-1881), the Baron Gaston de Saint-Maurice (1831-1905), the Prince Edmond de Polignac (1834-1901), the Marquis Gaston de Galliffet (1830-1909), and Charles Haas (1833-1902).

Tissot’s aristocrats at The Jockey Club

No one depicted this kind of rarified male better than Tissot, a French artist in exile, who lived and worked in London, the original home of the original Jockey Club. He perfectly captured the aristocratic male at his apogee in the twilight of the nineteenth century.

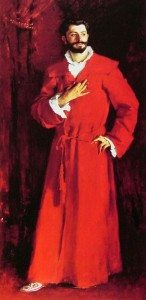

John Singer Sargent. Dr. Pozzi at Home (1881)

In fact, the greatest portraits of the these decades are devoted, not to women, but to these privileged peacock males: John Singer Sargent’s (1856-1926) Dr. Pozzi at Home (1881) and most of all, Tissot’s portrait of Frederick Gustavus Burnaby (1870). Alone amidst incongruous floral furniture, the British Captain of the Royal Horse Guards lounges at his ease, mustaches waxed and uptilted, cigarette at attention between his graceful fingers. To the eyes of an untutored American, Burnaby looks “French,” but “Fred,” as he was called, was decidedly English. In fact his mannered style, the epitome of male mannerism, was the very essence of all that was the British aristocracy at its peak and it was this aspect of all things English that wafted across the Chanel as “Anglomania.” The French aristocrats at the Jockey Club are echoes and copies of Burnaby, most of them without his adventurousness and bravery. There is an élan to the British male of this period and the French responded by eagerly adopting as are their favorite sports, from yachting to tennis to horseracing to the very concept of “sport” itself—all British exports–from their English counterparts.

Tissot’s Frederick Gustavus Burnaby (1870)

No where is the difference between the authentic English gentleman and the authentic French gentleman seen better than in the paintings of Gustave Caillebotte. In contrast to Burnaby’s misleadingly langurous long legged pose, Caillebotte’s well-to-do bourgeois males are causal and rather blunt. Like Mary Cassatt, he was able to capture the wealthy men au natural, in their habitat, in private moments. While most of his colleagues concentrated on female fashion, Gustave Caillebotte was concerned with male fashion and showed the world of the upper class male living in Haussmann’s new Paris in introspective luxury. These wealthy men seem idle and without purpose; they are rarely engaged in any meaningful activity and, in their pointless lives, seem to exemplify the alienation of modern life. But Caillebotte was also careful to observe the lower class male. At the Café (1880) shows that particular male, marked by class differences through the small bowler hat, the short casual coat, the floppy collar and tie, the hands shoved in the loose pants. His confidence, his ease in his surroundings, indicate a sense of upward social mobility, but he also wears his class-bound clothing with a certain resignation.

Caillebotte’s Lower Class Male

Caillebotte’s men tend to be at once active and passive, often separated from friends and family and women, set apart as observers or choosing solitude as a defense mechanism against the crowds of the city. Alienation is a common sub-theme running throughout Impressionism like a stain of melancholia, apparent in the psychological distance between men and women in the painting of Degas and Manet. In Caillebotte’s The Pont de l’Éurope (1876) shows a range of classes, gender, and métier: the elegant upper class male, dressed for display, a middle class woman, bravely walking alone, a lower middle class male in the distance, and in the foreground, a worker in a loose blue smock. This lower class male in wears a loose fitting blue over shirt, which allows him to do manual labor. In contrast, the upper class male, according to Balzac, supposedly wears “comfortable” clothes that allow for “movement,” but one suspects that the relative comfort of the wealthy man in the author’s comparison was made to the culottes and the lace cuffs of the aristocrats of the previous century.

Caillebotte’s The Pont de l’Éurope (1876)

Now that the very privileged were without the embroidered waistcoats, it was the top hat that truly marked the leisure class off from the laboring class, for the tall shiny funnel on the top of the male head made it impossible for him to bend over or move quickly. The tall black hat immobilized the male but set him apart, made him taller and grander, just as the volumes of clothing worn by his female counterpart kept her paralyzed and numb. Edgar Degas (1834-1916) made the shiny tall black “top” hat dominate his males in Portraits at the Stock Exchange (1897-9) which is not about portraits at all, unless one is studying the way in which the male personality is submerged beneath the cylindrical marker. One could argue that the middle class male, now firmly situated in a position of dominance, is using a black and plain costume as a disguise to hide in. Aristocrats of the past revealed themselves as privileged and reveled in their position by celebrating through flamboyant and excessive clothing that advertised their uselessness. The bourgeois male, learning from the past, hid the fact that he was equally rich and equally powerful and equally privileged behind a uniform that to the untutored eye looked the same, identical from man to man. But to those who mattered—those who could know—relative power was announced through details, clearly visible to the discerning and educated eye but invisible to the “mob.”

Degas’s Portraits at the Stock Exchange (1897-9)

The nineteenth century was a century of coming to terms with the eighteenth century and the explosions of revolutions towards its end. From 1789 to 1872 France had been in constant turmoil, punctuated with occasional decades of reconsideration. As with any revolution, or, in the case of France, several revolutions, there were winners and losers. In America, women and people of color—from slaves to Native Americans—were the losers, and everywhere middle class men of status and property were the winners. In France, the aristocrats or those who aped them were also the winners when the middle class males were preempted by being given a share of the power. After the frightening excesses of a series of upheavals, the upper and middle classes males in France could close ranks against the lower class males and women by keeping them from sharing in the political arena as long as possible. England, wary of the way the French had lurched from uprising to uprising, gradually gave up bits and pieces of privilege, a few laws here and a few rights there, to calm the agitation among their own people. Year by year the uprisings foretold by Karl Marx (1818-1863) were forestalled by these grudging and necessary laws and by the rising tide of disposable commodities that would so distract that part of the citizenry who would remain excluded from the “democracies” of Europe—the female.

Revolution of 1848

The next part of this discussion will focus on how fashion soothed the savage breast of the malcontented woman.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.