THE TROUBLESOME AMATEUR

Lewis Carroll (1832-1898)

A Question of Interpretation

For early photographers one of the most astonishing aspects of camera vision was the lack of control of the maker. The plethora of detail must have been particularly shocking for those trained in painting and used to making decisions as to what to include and what to eliminate. A photograph contained elements that, for painting, would have been irrelevant, but it also contained a record, captured unconsciously, if you will, by the action of light and chemicals. The disinterest of the camera aperture produced a lack of hierarchy of what was imprinted and the photographer had few options beyond framing to impose his or her intentions upon the result. The actual reality of photographic images contradicted the concept of the inventors who had wanted an instrument that “drew” or “copied” rather like human, which is the idea whenever the machine hand replaces the human hand.

But the camera eye is not at all like the human perception because the camera does not possess the human brain which selects and filters out material unimportant for the purpose of looking. The brain “looks” and “sees” and tabulates according to occasion: what you see is what you need to see. In addition, the brain’s act of vision is not innocent or naked; it is entirely conventional and what is “important” or “relevant” is determined by social conditions. If that is the case then it should is important to understand works of art within the context of their own time, for it is only within this specific period did the objects manifest meaning. Of course the “meaning” of a work of art cannot be “stopped” in its own time and later eras are fully entitled to derive other meanings–but what are the limits of the re-readings?

One of the problems with history is historians who tend to historicize the objects they study in terms of the prevailing attitudes of their own time. Although all historians are aware of the problem of interpretation, in some areas such as art history or literary history, ample latitude is given for analyzing the work of art or literature from the perspective of critical theory or individual interpretation. While insightful in most cases, there is always the risk of imposing a mind set that did not exist at the time and then proceeding as if the resulting scrutiny were an accurate reflection of the author’s intent. Called “the intentional fallacy,” an idea put forward by W.K. Wimsatt, Jr., and Monroe C. Beardsley, is a problem similar to the “pathetic fallacy,” a term coined by John Ruskin, the tendency to attribute to a long dead author an “intention,” often emerges when contemporary readers become uneasy with what they are seeing. In contemporary times, Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, who wrote under the name of “Lewis Carroll,” has been interpreted as a man who had a far too erotic interest in little girls. His photographs are treated as an extension of his supposed erotic desires –the “intentional fallacy”–and as bearers of his repressed sexual fantasies–the “pathetic fallacy.” Or as German writer, Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) said, “Photography makes aware for the first time the optical unconscious, just as psychoanalysis discloses the instinctual unconscious.”

It would be hard to imagine a more unlikely candidate for pedophilia. Charles Lutwidge Dodgson was born into a very religious family, practicing the Anglican faith of the “high church” variety, meaning that this branch was very close to the Catholic Church or the (Anglican) Church without the Pope. Many of his family members, including his father, were priests in the church, but rather than follow in the family’s footsteps, Dodgson attended Christ Church College where he stayed for the rest of his life as a lecturer in mathematics. There was an all important catch, however, for this guaranteed life time job, which he held for forty-seven years, and the stipulation was that he had to remain celibate and that he had to take holy orders. Although Dodgson apparently adhered to the celibacy (unmarried) aspect of the bargain, he managed to avoid becoming a practicing clergyman. He was ordained as a deacon (a lay minister) who never preached. As a scholar, Dodgson wrote and published An Elementary Treatise on Determinants (1867), Euclid and His Modern Rivals (1879), and Curiosa Mathematica (1888). But these are not his best remembered books.

In addition to being a mathematician, Dodgson had a clever mind, fascinated with puzzles and games and ciphers, and he transformed his childhood love of storytelling to his many brothers and sisters into a writing career under an assumed name. The man who could not get married and have children of his own had a perhaps natural interest in the children of his friends and his inclinations towards being a father found an outlet in his children’s stories, such as Alice in Wonderland, written under the name “Lewis Carroll.” “Lewis Carroll” was a rearrangement, an anagram of his real name, and it is under this nom-de-plume that he would write a series of famous books and poems, all fanciful, nonsensical and wise at the same time. Carroll who had been a stutterer since childhood, wrote to other children this warning poem:

Learn well your grammar

And never stammer.

Eat bread with butter;

Once more, don’t stutter.

A man of many talents, Carroll was also a photographer and belonged to the ranks of gifted amateurs that featured prominently in England at the end of the nineteenth century. Today there is no equivalent to the “amateur” of Victorian times; one is either an fine art photographer or a commercial photographer. But in the time of Carroll, there was a respected tradition of the well-to-do upper class hobbyists who had serious careers in photography, dating all the way back to William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) and including his contemporary Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879). These amateurs tended to use friends and family and neighbors as subjects. Many of these images show the Victorian penchant for performance and dressing up. For example, Roger Fenton (1819-1869) photographed Queen Victoria’s children dressed up for amateur theatricals.

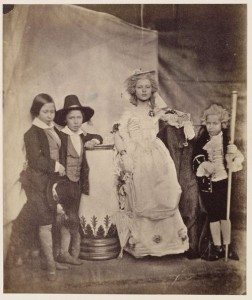

Children of Prince Albert and Queen Victoria performing Les deux petits Savoyards

Likewise Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught was posed by photographer Leonida Caldesi without a shirt. Caldesi, a portrait photographer from Florence Italy, was summoned by the Queen in 1857 to the Isle of Wight to photograph her children. Arthur seems none too happy during his ordeal of having to pose for long exposures, but in Victorian times, children were considered the epitome of innocence, signified by nudity often seen in photography.

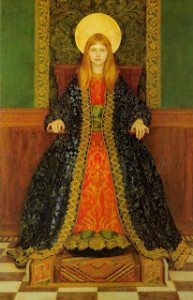

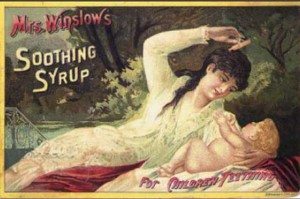

From fine art to advertising the images of children were omnipresent in the Victorian era, conveying the prevailing concept of childhood as a special time and that children should have a special status. The protective privileges accorded to childhood and to children was limited to the children of the upper and middle classes. In fact, Prince Albert cautioned against the political movement to prevent child labor because children, for the poor, were a form of economic capital, and a child as young as four or five could contribute to the family income.

Thomas Cooper Gotch. The Child Enthroned (1894)

According to Thomas Richards in The Commodity Culture of Victorian England: Advertising and Spectacle, 1851-1914 (1990), Victorian advertisers, pioneers in creating a climate of consumerism, recognized that the image of a child could sell a product. Richards quoted Victorian advertiser, William Smith as stating in 1854, “It is hardly credible what wonderful advertising mediums children are.”

A child working in a mine.

There is an interesting series of child labor in Victorian times The Children who Built Victorian Britain available on YouTube.

As the contrast of the three images above attests, childhood was a class-based condition. On one hand, the upper-class was enshrined as a paradigm of lost adult innocence, on the other hand, the child was commodified and marketed, and behind all the visual culture of an idealized childhood was the labor of thousands of poor children who could not be educated and who often died far too young from their exertions, all in the service of the Industrial Revolution. It is in this contradictory social situation of the visible child and the invisible child that the photography of Lewis Carroll can be best understood. Carroll took up photography in 1856, beginning not with the outmoded Daguerreotype, but the latest method of collodion, using the wet plate method. Although Carroll took portraits of adults, it was his photographs of children, little girls, that have caused the most contention and consternation.

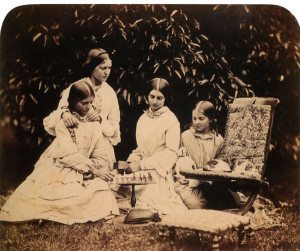

The Liddell Girls, Alice on the left

As Jenny Woolf noted in her interesting article in the Smithsonian Magazine in 2010, “Lewis Carroll’s Shifting Reputation,” the questioning about the little girls began in the 1930s. As painter Georgia O’Keeffe could attest, the 1920s and 1930s were the golden decades of Freudian inspired art criticism. Freud understood childhood to be sexual and that children were sexual beings, an insight that scandalized his peers, but the concept needs to be tempered by the understanding that Victorian children, pampered like pets and disciplined like adults, were actually highly socialized beings, constructed by adults in their own image. Twentieth century interpretations of Carroll’s image of little girls have looked past the context of the times and have performed armchair psychoanalytic interpretations of his intentions, declaring him a pedophile, projecting his unhealthy interest in girls through the aperture of his projecting camera lens. Such interpretations deny agency to Carroll’s subjects who were undoubtedly invested in the game of dressing up and posing as a performance that would please themselves, the photographer, and the parents who gave their consent to these photographic sessions.

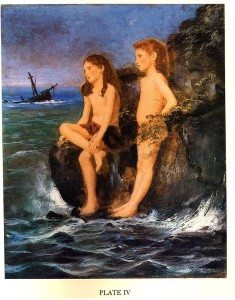

Photograph taken by Lewis Carroll, then coloured by Anne Lydia Bond on Carroll’s instructions

The most problematic images are those of Alice Liddell (1852-1934), one of the nine children of the Liddell family, Henry and Lorina, close friends of Carroll. The problem seems to rest mainly in the fact that she was his favorite child subject and that he singled her out for so many images. But Carroll was friends with all the children as Woolf put it, “Like many Victorian bachelors, he became a sort of uncle to his friends’ children, making up stories and games and taking them on short trips; the role ensured him a warm welcome in many homes.”

As Woolf explained,

Of the approximately 3,000 photographs Dodgson made in his life, just over half are of children—30 of whom are depicted nude or semi-nude. Some of his portraits—even those in which the model is clothed—might shock 2010 sensibilities, but by Victorian standards they were…well, rather conventional. Photographs of nude children sometimes appeared on postcards or birthday cards, and nude portraits—skillfully done—were praised as art studies, as they were in the work of Dodgson’s contemporary Julia Margaret Cameron. Victorians saw childhood as a state of grace; even nude photographs of children were considered pictures of innocence itself.

In discussing the possibility of photographing one 8-year-old girl unclothed, Dodgson wrote to her mother:

“It is a chance not to be lost, to get a few good attitudes of Annie’s lovely form and face, as by next year she may (though I much hope won’t) fancy herself too old to be a ‘daughter of Eve.’ ”

Likewise, Dodgson secured the Liddells’ permission before taking his now-famous portrait of Alice at age 6, posing as a beggar child in a tattered off-the-shoulder dress; the family kept a hand-colored copy of it in a morocco leather-and-velvet case.

Although childhood was a special time for the well-to-do Victorian girl, her childhood was a short one. Most upper class young girls “came out,” or were considered adults to be presented to society, by age fifteen or sixteen. Although the legal age of marriage without parental consent was twenty-one, most women married well before that age and statistically did not live beyond age forty. It was not uncommon for an older man to take a liking to a young girl and wait a few years and marry her. Queen Victoria’s oldest daughter was engaged at fourteen. However, Carroll, employed by Christ Church, could not contemplate marriage and was required to be celibate, so marriage was not conceivably available for him. However, the author was a normal human being and no doubt such a life was difficult–he wrote of his desires–but celibacy was a safe life for a quiet and retiring man who found refuge from his own awkwardness in telling stories to children.

Alice as the Queen of the May

It is likely that his photography was part of the home-based entertainment in a time before television became a caretaker for children. The character “Alice” appeared in a story Carroll told to the Liddell children on a boating excursion, which was an example of how adults spent time entertaining children, who were treated to a great deal of attention from their nurses, governesses, parents, and the friends of their parents, unmarried men and women. Although there seems to have been a break in his association with the family in the early 1860s, he published a sequel Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There in 1871. Part of the culture of the social construction of children was story-telling, whether through reading books or performing in plays or creating one’s own stories, often with didactic and moral content. Carroll had been a natural story teller since childhood and he carried his gift into adulthood, writing, as did many authors, for a large market of children’s books. Given that one and three of the Victorians were children, Carroll would have had a very large market and an appreciative audience of rapt children.

Certainly he had a gift for bringing out the best from the children he placed in front of a camera, revealing their budding personalities, as though the photographer and the child were playing a magical game of make-believe, a dress rehearsal for adulthood. According to photo historian, Helmut Gernsheim, Carroll “must not only rank as a pioneer of British amateur photography, but I would also unhesitatingly acclaim him as the most outstanding photographer of children in the nineteenth century.” But, even in his own time, Carroll apparently encountered suspicions of his motives. In 2008, Mail Online published an excerpt from a letter written to Alice Liddell that had a suggestion of rumored impropriety,

The letter was written in his rooms at Christ Church College in February 1877, when he was 43 and Alice was 25. Although the name of the addressee has been scribbled out it appears to begin ‘Dear Miss Liddell’. Written in his customary violet ink, it reads: “Thank you for the sight of the pretty photographs, but don’t keep the child in for me – I am fearfully busy – and what could Miss Lloyd have been thinking of to say such things of me? ‘She must have taken some remark of mine about liking children and have said to herself for “some” read “all”, for “girls” read “boys” and for “ten” read “two”–such a method of exaggeration is wholly unfounded, and yet she professes to be an admirer of Dr Liddon. Believe me.” It is signed “Yours very truly, C L Dodgson.”

The recently discovered letter was noteworthy because Alice’s mother destroyed the correspondence between her daughter and Carroll. Only twelve letters are known to have survived. In addition, adding to the mystery, after his death, Carroll’s family removed the section of his diary which were devoted to the year 1863, the year of the breech with the Liddell family.

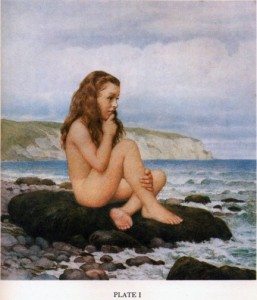

Evelyn Hatch

In the 1999 essay, “Take Back Your Mink: Lewis Carroll, Child Masquerade and the Age of Consent,” Lindsay Smith wrote of how Carroll negotiated with the parents for consent to photograph their daughters. Permission consisted of when and where the child would be photographed and which costumes, often borrowed from theatrical companies, would be worn or not. The photographer wrote of the costumes or outfits to be worn in very specific detail and kept props in his rooms to enhance the performance. Alice performed as a poor child, sadly a common sight in London, obviously not comprehending the social reality she mimiced in such a picturesque fashion.

Beatrice Hatch

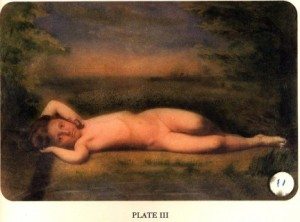

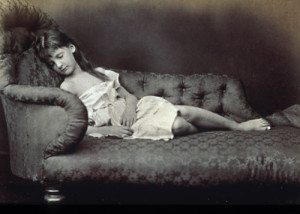

Xie (nickname for Alexandra) Kitchin Lying on a Sofa

Alice, age seven

For Carroll, it was important that the little girls to be genuine children because in his time, the “age of consent” for sex was thirteen. Thus as Smith pointed out, through bargaining with the parents for the right to photograph their young daughters, Carroll shifted responsibility from himself to the compliant adults. He strategy, as Smith noted was that he would stress the child’s “innocence” making it difficult for the parent to refuse consent. One has only to recreate the request in today’s terms: imagine getting a letter from a respectable clergyman asking you permission to photograph your daughter, perhaps in her innocent nudity, alone, in his chambers in the College or in his private home, what would your reaction be? Smith, who has written some of the more interesting work on Carroll, suggested that the elaborate preparations for costumes and consent were symptoms of the photographer’s need to hide his real motivations from himself:

For what Carroll does not want–as so many critics have suggested–sexual reciprocity with the child. What he does want is the freedom to perform his visual compulsion, through a repeated photographic fixing of the minor; to perform, that is, in the knowledge that the representation of his desire, in the little girl personating the consenting subject (and its dependence upon the medium of photography), is rendered invisible, its visual register readily absorbed by the social and legal discourse of childhood of his day.

Carroll’s attitude towards little girls mirror the changing attitudes of his time and his photographs strive to capture that narrow window between babyhood and adolescence, a mere six or seven years, when young girls were “innocent.” Beyond the factual documents recounting his discussions with the parents and the girls, which described how he set up a compromising situation and struggled to wrest the photographic sessions within the bounds of respectability, we have no evidence of his ulterior motives (“intentional fallacy”) as they may be manifested in his creation of little girls as a visual spectacle and, perhaps, as an erotic one (“pathetic fallacy”) in his photographs. The performative collaboration between Lewis Carroll and his little girls was both part of his time and located on its fringes as well, bordering fantasy and fetish in photography.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.