Henry Tonks (1862-1937)

Surgery as Art

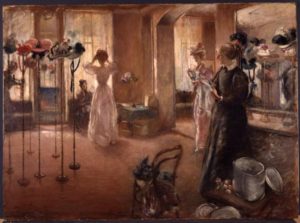

An examination of the oeuvre of the feared and respected teacher, who dominated the lives of fledgling students at the famed Slade School of Art, reveals that Henry Tonks was not a great artist himself. Unlike Walter Sickert, he was not even particularly interesting in either his content or painting style. His early twentieth century work was a conservative dark toned version of post-Impressionsm, bland and rather boring. Many of his paintings were informed by Edgar Degas, but Tonks discarded the unique compositional effects of the Impressionist predecessor. As a teacher he was most famous for his illustrious students, the gifted generation that went to the Great War, hated it, and painted its horrors. Trapped in his own artistic time, Tonks disapproved of them all, Nevinson, Wadsworth, Spencer, Nash, none of whom could measure up to Degas. But the drawing taskmaster had trained them well. And Tonks left one other unexpected legacy, a technique called “tonking,” in which excess oil can be removed from a canvas with an absorbent piece of paper. The useful technique was widely used in art schools until the late 1950s when acrylics began to replace traditional painting media.

Henry Tonks. The Hat Shop (1892)

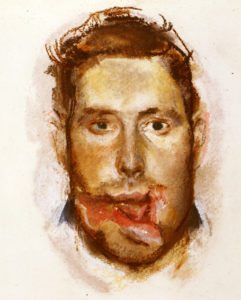

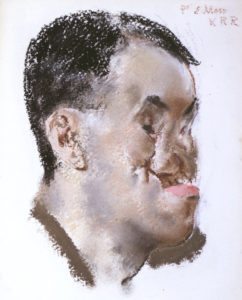

Oddly enough, despite the awe and terror he inspired as a teacher, as an artist, Tonks did not come into his own until he confronted one of the most painful tragedies of the young century: men without faces. Working hand in hand with a pioneer plastic surgeon, painting the stricken men with compassion and tact, Henry Tonks produced a private and, for the most part, secret record of the most feared disfigurement of the Great War: defacement, loss of face, loss of identity, loss of individuality. In his series of studies, done in the granular medium of pastel, Tonks paused his career at Slade and painting an unexpected portrait of war, the men who wore its toll on their faces. It is here, in these disembodied faces, that Tonks finally arrived at an original style–original not in execution–but in the fearless confrontation with faceless men, whose wounds were so hideous that they were not to be viewed until they were healed.

War is notorious for bringing about advances in technology, most of which involves improvements in killing machines; but every now and then, something positive emerges from military necessities, and, often, strides are made in medicine. The four years of the Great War produced a very specific set of medical challenges, notably, treating the effects of gas attacks, that were unique to that particular war. But less well known was the impact of the machine gun, which destroyed lower limbs as the soldiers who were advancing towards the enemy trench were literally mowed down by the scything actions of the merciless machine gun. There were 41,000 British soldiers who survived amputations and more than 50,000 French soldier who often experienced amputation done by guillotine in France had to live the rest of their lives with the chronic and the then incurable pain of the “phantom limb” which had to be replaced by a prosthetic limb. Wiring for CNN in 2014, Thomas Schlich stated, “Virtually every device produced today to replace lost body function of soldiers returning from our modern wars — as well as accident victims, or victims of criminal acts, such as the Boston Marathon bombings — has its roots in the technological advances that emerged from World War I.” But there was another medical advance that has long been kept confidential for reasons of the soldiers’ privacy, the extraordinary advances in plastic surgery or reconstructing a destroyed face.

Trench warfare produced a new crop of terrible injuries–when a soldier popped his head up above the trench line, a sniper could easily pick him off. But a bullet wound was relatively straightforward compared to the other major danger to faces, shrapnel, which exploded into tearing shards, decimating the face. Medical technology had advanced to the point that these men were able to survive these terrible wounds, leaving the medical profession with the task of caring for and repairing these victims. Plastic surgery itself was nothing new and can be dated back to 800, according to an account of the practice in India, but the first book, passing on knowledge to further generations was written by Gaspare Tagliacozzi (1545-1599), who dealt with facial wounds from dueling during the Renaissance. In his book, De Curtorum Chirurgia per insitionem (1597), Tagliacozzi explained how he used the “arm flap” as material to reconstruct the nose. The modern “father of plastic surgery” was Harold Delf Gillies (1882-1960), a New Zealander, who published Plastic Surgery of the Face in 1920, which revealed groundbreaking new techniques in reconstruction. Gilles considered restoring the face to be an art form and referred to his work as a surgeon as “aesthetics,” indicating a philosophical position for a medical practice–the reason for surgery was to reclaim the original “beauty” of the human face as far as possible.

Although the idea of transferring flesh from one part of the body to repair another was well-known, the surgical techniques were crude until the Great War. Gillies had been trained as a surgeon and joined the newly formed Ear, Nose and Throat Department in 1910 at St Bartholomews Hospital in London, but did not become interested in plastic surgery until he served in the Great War. Upon seeing the damage done to human beings by the new modern weapons–“men burned and maimed to the condition of animals”–he became determined to help the soldiers with facial wounds. After watching the French, who were also experimenting with facial reconstruction, Gillies asked for and was granted a request to set up a special British unit for plastic surgery at the Cambridge Military Hospital at Aldershot. Gillies was among the first surgeons to understand the importance of reconstructing the ruined faces of the soldiers not just in terms of functioning–eating and breathing and speaking–but also in terms of appearance. The mutilés who returned home were unrecognizable to their friends and families and to themselves, a traumatic experience, a literal “loss of face,” which psychologically disturbed the victims and their families. For full recovery, it was necessary for the soldier to be able to appear in public without frightening those he encountered, and it was Gillies who recognized that restoring a face–one’s sense of selfhood—was a step towards restoring peace of mind.

Until recently, the work done on the victims of the Great War was a private and almost secret body of knowledge. The facial disfigurements were so grotesque and horrifying, indeed so alien and unprecedented, that the mere existence of the surviving soldiers made the government and the public uneasy. Their faces, the appearance of the mutilated soldier in the streets raised uncomfortable questions about the cost of war and the condition of those who were paying the price. In his 2014 book, Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning: The Great War in European Cultural History, Jay Winter wrote of the significance of the wounded and how those with conventional wounds played a part in the project of memorializing the War: “On 14 July 1919, a victory parade traversed the Champs Elysées in Paris. Foch, Joffre, Pétain, Clemenceau were there. But leading the way, and changing the entire tone of the occasion were the mutilés de guerre. What had started as a victory celebration turned into a sombre moment of mass mourning.” However, as Emily Mayhew pointed out in the beginning of Wounded: A New History of the Western Front in World War I (2013), that “Yet in the historical record of the First World War, the wounded and the men and women who cared for them are an undiscovered, somehow silenced group.”

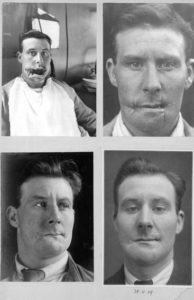

Henry Tonks. Portrait of a Wounded Soldier before Treatment (1916-17)

One of the most significant articles on facial disfigurements during the Great War was written in 2011 by Suzannah Biernoff for the Social History of Medicine. In “The Rhetoric Disfigurement in First World War Britain,” Biernoff noted that “the loss of one’s face..is perceived as a loss of humanity.” The extent of facial injuries was shocking with some 60,500 soldiers with head and eye injuries that required a joint effort between surgeons and artists. As she reported, “Many soldiers were shot in the face simply because they had no experience of trench warfare.” “They seemed to think they could pop their heads up over a trench and move quickly enough to dodge the hail of machine-gun bullets,” wrote the American surgeon Fred Albee. Military medical archives contain exhaustive visual evidence of the injuries inflicted by machine guns and modern artillery on the faces of young British men. As Mayhew pointed out, these particularly grievous wounds had a special name: “a ‘Blighty wound’ or ‘Blighty one’ meant that an injury was so severe that the sufferer was certain to be sent home either for treatment or medical discharge. The word is still used in the British Army today.” In France, as Winter reported, there were specific organizations dedicated to the special needs of the gravely wounded.

In 1916 a French association of the disabled started to publish a newspaper with the following title: the Journal des mutilés, réformés et victimes de guerre. It broadcast the existence of a host of local groups, under the sponsorship of mayors or prefects. Out of this activity came a large national organization. The first congress of war wounded met at the Grand Palais in Paris on 11 November 1917. Delegates named by 125 societies representing 125,000 disabled men were there..One of the most poignant of such groups was the association of disfigured men, those with face wounds so terrible that they bought their own property for collective holidays and rest.

Given that there were at least ten million wounded who would permanently bear the scars of the War for the rest of their lives, the subsequent neglect and forgetting of these victims was nothing short of tragic. According to Winter, the numbers of the wounded and their unfamiliar needs and the desperate straits of their families far exceeded the ability of any government to deal with their demands. Most of their final stories are unknown, but the accounts that exist were often punctuated by suicides and loss of will to go on with their lives with no face. Given the collective pain and denial circulating around the facial wounds, it is not surprising that the medical records were suppressed. As Biernoff noted, “The response to facial disfigurement was circumscribed by an anxiety that was specifically visual. Patients refused to see their families and fiancés; children reportedly fled at the sight of their fathers; nurses and orderlies struggled to look their patients in the face.” Until the past few years, however, these X-rays and surgical diagrams, photographs, and stereographs, plaster casts and models were rarely publicly exhibited. It has even been claimed that they amount to a ‘hidden history’ of the First World War.” And yet the long-term project of restoring these men to some semblance of a healthy and useful life was an artistic one. According to Biernoff, this hidden history could be viewed immediately during and after the war through the series of pastels the famous artist Henry Tonks, a famed teacher from the Slade School of Art, who worked with Harold Gilles during 1915 to 1916 at Aldershot. These studies of the ruined faces of young men were the “before” records, made at the beginning of what would be a long process, often lasting for years, were briefly shown at Queen’s Hospital at Sidcup. Immediately after the War, these sketches disappeared, not to re-emerge until 2002, when they were shown, along with the photographic records of the restoration process, in the Strang Print Room at the University College London. Finally in 2007, these pastels joined the records of the work of Gillies in the Gillies Archives.

Henry Tonks. Portrait of a Wounded Soldier after Treatment (1916-17)

This gap of visuality, almost one hundred years, mirrors what Biernoff called a “culture of aversion,” that surrounded the wounded faces. She wrote, “This collective looking-away took multiple forms: the absence of mirrors on facial wards, the physical and psychological isolation of patients with severe facial injuries, the eventual self-censorship made possible by the development of prosthetic ‘masks,’ and an unofficial censorship of facially-disfigured veterans in the British press and propaganda. Unlike amputees, these men were never officially celebrated as wounded heroes.”

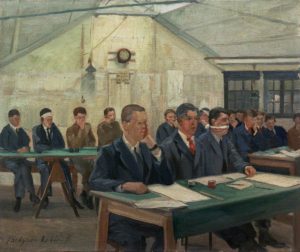

J. Hodgson Lobley. The Queen’s Hospital for Facial Injuries, Frognal, Sidcup: The Toy-makers’ Shop (1918)

A painting by J. Hodgson Lobley shows the fate of the soldiers with facial wounds, kept carefully out of public view, perhaps abandoned by friends and family. While waiting to be helped, the wounded men occupied themselves by making toys, as illustrated here, or mended watches and clocks, and they learned a rather odd assortment of trades, such as coach-making and dentistry. The aim of the hospital was to retrain the soldiers, giving them a trade for their civilian lives. Moreover, because these soldiers had lost their ability to be a man, in other words, to appear in public as a fully actualized human being, those with very severe facial disfigurement injuries received lifetime pensions. As American surgeon Fred Albee, a pioneer in bone grafting said, “It must be unmitigated hell to feel like a stranger to yourself.” It was out of severe necessity that Harold Gilles established a specialized unit dedicated to facial reconstruction at the Frognal estate, his own private and secluded country home. Here, the patients, many of whom refused to return home, could stay during what would be years of procedures and remain among doctors, nurses and companions who understood the nature of their disfigurement. At Sidcup and Frognal, the “man” himself could be restored, while at the same time, the science of plastic surgery was being advanced.

Henry Tonks. Portrait of a Wounded Soldier before Treatment (1916-17)

The role of Henry Tonks was a painful one. It was he who somehow convinced these deeply depressed men to face him and allow him to scrutinize what was literally a loss of face. Tonks had not always been an artist but had, in fact, begun his career in medicine, finding his way to Slade as an art teacher at mid life. Working closely with Gillies was, for Tonks, a return to his own beginnings as a medical student who had been lured away by art. The intimacy of the portraits of these wounded men stand in strong contrast to the series of paintings done at Sidcup by Lobley. Although this artist showed the operating theater where the doctors worked on multiple patients at the same time, the views are discrete and distant and reassuring to the audiences. But behind the white gowns and the seeming assembly line like care of the multiple patients, lies a story of uneven knowledge and on going learning on the part of doctors. Ana Carden-Coyne discussed the difficulty of using anesthesia in her 2014 book, The Politics of Wounds: Military Patients and Medical Power in the First World War: “There were no universal method of anesthesia and the debate continued throughout the war. Surgeons often criticized each other in medical journals for overuse of local anesthetic injections combined with nitrous oxide..or use of rectal anesthesia..Facial reconstruction patients could not use the facecloth method, but had to sit upright to stop blood flowing into the mouth. Ether via the rectum was one alternative, but it cant considerable discomfort.”

John Hodgson Lobley, The Queen’s Hospital for Facial Injuries, Frognal, Sidcup

All of the official artists were part of a larger effort, not to inform, but to memorialize the War, to make a case that the cost of winning was worth the sacrifice and to show military families that the causalities were being well taken care of. As would be expected, Lobley’s work was very careful to disguise the actual agonies endured by soldiers who often endured multiple operations for years. Actual photographs of the soldiers in their pre-operative condition are difficult to view, even today and the softened portraits by Tonks had a gentle haze of compassion which was more sensitive than the merciless glare of the camera.

In writing of the pastels of Tooks, Suzannah Biernoff stated that “in Tonks’ drawings of wounded soldiers, the subject is doubly alienated from himself. In the first place, the institutionalisation of these men (first in the military, then as long-term and usually recurrent residential patients) disconnected them from the social and physical fabric of their ordinary lives, their sense of a past and future meaningfully connected to the present. As well, the privileged signifier of subjectivity, the face, now signifies trauma.” In contrast to conventional paintings of wounded soldiers done by British artists, Tonks was not under any obligation to shield the public or the men themselves from scrutiny. The result was a record, the first of its kind, of defacement, a crisis in military morale and in the medical profession. Biernoff continued, “..the residual fragments of individuality conveyed through posture, gaze, clothing and framing, fragments that only foreground the shocking violence of the injuries. These are anti-portraits, in the sense that they stage the fragility and mutability of subjectivity rather than “consolidating the self portrayed.” The achievements they celebrate are not those of the men we see (though to be alive at all was an achievement of sorts). The personality, the hero, of these untitled portraits is the pioneering surgeon, his inventiveness, skill and dedication told through the simple narrative structure of ‘before’ and ‘after.'”

Tonks, a taciturn man at best, seems to have joined his medical and artistic knowledge of the anatomy of the human face to make studies that would serve as tools for Gillies who was subsequently able to judge his own and the progress of his patients. As the artist of these works, Tonks remained silent and seems to have not discussed or written about his experiences during the war. In passing he mentioned his work with these men as “excellent practice,” an enigmatic phrase. The photographs taken of the mutilated men to record the operations as each procedure slowly restored some semblance of a face when compared to the original pastels are nothing short of astonishing. But, as extraordinary as the accomplishments of the artist and the surgeon in their joint efforts, the images, whether pastel or photographic are mute to the psychological state or to the physical pain and suffering of the men who gave their trust and belief in these two remarkable artists, Harold Gillies and Henry Tonks.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.