Stanley Spencer (1891-1959)

The Artist in the Balkans

Part

One

There was no possibility that Stanley Spencer, recently graduated from Slade School of Art in 1914, would ever join up the be a soldier in what would be named The Great War. The painter was too small and too frail for the rigors of actual marching and fighting, but, like most of the young mean of his generation, he felt a strong sense of responsibility to his nation. He came from a gifted family tucked away in a delightful English village, called Cookham, located in Berkshire on the banks of the Thames. Spencer was not the only artist in the family. His father was a fine musician and expert organ master, and his brother, Gilbert, became an artist, specializing in landscapes. Adding to the quintessential Englishness of the setting, the family home was named “Fernlea.” His first self-portrait, painted on the eve of the War was executed in a cottage named “Wisteria.” From the start, Spencer’s character was a solitary one. He would be lost in his drawing, he would take long walks through the lovely countryside–a site where time stood still. Spencer’s early life was pulled between the dialectic of the sophisticated set at Slade and the timeless perfection of nature gently improved, Constable like, of the Village’s surrounding countryside. When he was still in his teens, Spencer, who had been home schooled, began to attend a Technical School of this art training. The prosaically named institution was located in “Maidenhead,” a nearby town, the name of which resonated with Medieval memories.

Precociously artistic, Spencer ventured further afield to the sophisticated and fast-paced city of London, a city that a was facing the new century with aggressive efficiency. A further culture shock awaited him at the Slade School of Art, where Spencer, educated in Victorian values, encountered Bohemian and freethinking and modern art students. Even in a class uncommonly full of gifted students, presided over by Henry Tonks, who should send this generation to war. Spencer’s classmates, Edward Wadsworth, Christopher Nevinson, David Bomberg, William Roberts and to a certain extent Paul Nash, were impacted by Cubism and Futurism and Vorticism, while he was steeped in the Renaissance, specifically the Early Renaissance of the Italian masters. Spencer’s closest friend and great admirer, Mark Gertler, was sophisticated, future member of the Bloomsbury set. Surely Dora Carrington, the femme fatale of the group was around, but Spencer, like the Victorian town of Cookham was frozen in time and would not explore sex until after the Great War. Therefore, he was one of the few young men who were not in love with her.

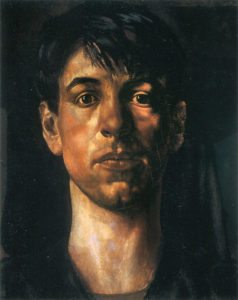

Stanley Spencer. Self-Portrait (1914)

In order to understand the profound sense of dislocation Spencer must have experienced when he went to serve in the War, it is necessary to remember that he was so attached to Cookham that he even commented from London between the art classes in order to have tea at home. In retrospect, Spencer’s life in the Village was a lingering slice from a previous century, rooted in tradition and yet intelligent, even intellectual, and undisturbed by the passage of time. Even today, Cookham seems frozen in a beneficent amber, and it is easy to understand the profound disruption of an unprecedented modern war of annihilation upon the village green, the Tudor-styled houses, the boats on the Thames, the pub and the general air of genteel peace. For Spencer, the Village was as magical as the home in which he grew up. As he later explained, “When I lived in Cookham I was disturbed by a feeling of everything being meaningless. Quite suddenly I became aware that everything was full of special meaning, and this made everything holy. The instinct of Moses to take his shoes off when he saw the burning bush was very similar to my feelings. I saw many burning bushes in Cookham. I observed the scared quality in the most unexpected quarters.”

Blessed with a deeply felt sense of place and the things that populated his world, Spencer naturally assumed that religious figures would live in Cookham or visit from time to time. This sensibility of Renaissance realism, the notion that ordinary objects are animated with meaning and symbolism can be seen in the Merode Altarpiece from the workshop of Roger Champin and updated in the paintings of Stanley Spencer. When he joined the military, Spencer took with him his steadfast belief that religion makes sense of the world and it probably kept him sane and grounded. He joined the Royal Medical Corps, the same destination as Christopher Nevinson, Unlike Nevinson, he did not go to France but to Bristol, where there was a huge hospital, the Beaufort War Hospital. Beaufort, it must be pointed out was near “Fishponds” and was a former lunatic asylum converted in to take on the huge influx of wounded, pouring in from France. Although almost a thousand patients were redistributed, forty five were kept on to care for the grounds. The new hospital had almost 1500 beds and in its first year of operation treated over 11,000 cases, just a small fraction of the overall causalities being disseminated towards the hospitals in port cities.

Beaufort was but one of the circles of medical hell, but its working population of functional “lunatics” made it a uniquely surreal experience for Spencer who wrote in his year in the institution, “I had to scrub out the Asylum Church. It was a splendid test of my feelings about this war,..But I still feel the necessity of this war, and I have seen some sights, but not what one might expect. The lunatics are good workers and one persists in saluting us and always with the wrong hand. Another one thinks he is an electric battery..” In the Summer of 1916, the general “war” hospital became specialized into the Orthopedic Center for the area and Spencer moved on to Macedonia, one of the ancillary battles of the war. Here on the Macedonian front, he joined the infantry and was a stretcher bearer. The Greek front has been often glossed over in favor of the mythic Western Front. Loretta Proctor filled in this blank with her book The Long Shadow writing, “One always heard tales and memories and documentaries about Ypres, the Somme, Passchendaele and all the other haunting names of the Western Front. We could conjure up pictures of slithering mud, cold trenches, stunted trees and other harrowing scenes of Western battle zones. But who knew much about Macedonia and the freezing Vardar winds, the barren but beautiful mountains, the treacherous ravines and raging summer heat filled with malarial mosquitoes?” However as Winston Churchill noted, “It was upon this much-abused front that the final collapse” of the Central Empires first began.”

Spencer spent the rest of the war at Salonkia, a Greek port, defined by the British and the French. But his service from 1917 on was more complex–he enlisted in the infantry and became part of the Royal Berkshires, a comforting connection with home. Spencer became one of the few artists to undergo the ordeal of the trenches as a common soldier. He described his duties:“Our activities consisted of outpost duty and patrolling the wire at night and during the daytime doing odd fatigues, just outside our dugouts. In the evening just before sunset, the Bulgars started a barrage. The shells dropped uncomfortably near and I was glad when getting into the outposts, we were able to take cover in a communication trench.” Actually this division spent so much time digging trenches that a they were referred to as “gardeners.” Spencer would eventually become a stretcher bearer, a noncombatant who risked his life to save the wounded soldiers. “I went out with a captain and he was hit and sank to the ground. His hand went up to his neck and I saw a gaping bullet wound in it. I bandaged the wound the best I could and called for stretcher-bearers. I helped to support the captain, who was paralyzed,” Spencer said.

Macedonian Greece had broken from the weakening Ottoman Empire and fought on the side of Triple Entente, fighting for self-determination. The allies sent in troops which assembled into a motley group grandly called the Army of the Orient. This Army spent much of its time in small but costly skirmishes, each adding to the cluster of deaths of Russians, French, Serbians, Italians, and British, whittling away at the Army. In September of 1918, the forces that were left finally moved aggressively with British planes experimenting with yet another means of killing, strafing the Bulgarians on the ground. This long campaign reminded participants and on-lookers alike, of the starting place of the War, the Balkans, the site of tribal,cultural and political ferment for hundreds of years. This Eastern front was important to England, which had assaulted the Turks at Gallipoli two years earlier, because of its global trade interests in the region. The French could therefore always be counted on to show up, shadowing Great Britain, making Regardless of the post-war ambitions of the United Kingdom, the front was an important one as it sealed the Austro-Hungarian Empire at its rear or, when attacked, could end the war in a single stroke, by dividing it from the Ottoman Empire, which collapsed in October 1918. With that not unexpected event, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg stated sadly, “As a result of the collapse of the Macedonian Front… there is, so far as can be foreseen, no longer a prospect of forcing peace on the enemy.” German would be forced to surrender.

After the Great War, Great Britain was faced with many tasks, the first being showing and explaining this decimating conflict to the suffering citizens who had invested so much and had lost so much. Part of this needed justification was memorializing and thereby sanctifying the War. The Ministry of Information which had overseen the verbal and visual versions of the War between 1914 and 1918 continued to retain control of its depictions. The Ministry commissioned Spencer to document his time in Macedonia intended towards a never-built Hall of Remembrance. Spencer’s work, Travoys Arriving with Wounded at a Dressing Station at Smol, Macedonia, September 1916 seems straightforward and prosaic until one realizes that the vantage point is from above, perhaps God watching in amazement. The major figures are the mules, best suited for transport in the rugged mountains. The travoy, from the French word, travois, coined when the explorers saw the Native Americans on the Plains transporting their heavy loads on a sled, towed behind a horse. The travoy, a frame used to restrain the horses, has been attached to mules, presumably Greek, to drag the wounded to the lifesaving hands of the doctors. The animals have carried a line of stretchers filled with wounded soldiers, directly to the operating theater. The mules arrive two by two with the wounded soldier tucked snuggly between his rescuers, triggering a memory in the painter of snuggling between his parents in their bed. The mules reappear in the saga in the Sandham Chapel, mules who have died for their country and are rising up by the power of Christ, ears pricked with anticipation.

Seen from the back, the mules gaze with apparent interest into the brightly lit scene of doctors frantically at work in an impossibly clean and unbloodied sanctum. The stretcher bearers wait by their patients for their turn to carry the wounded soldier into the brightly lit performance. This metaphorical connection to the performing arts came, not from Macedonia, but from Bristol. Spencer recounted, “Two hundred patients or more would arrive in the middle of the night – this was disquieting and disturbing. One had just got used to the patients one had; had mentally and imaginatively visualized them. I have to move patients with their beds from one ward to another or perhaps to the theatre.” The scene set by Spencer is unfamiliar and is puzzling and hard to decipher, not because the artist is inexact but because this part of the conflict has been overshadowed. And yet over a year’s time, a million men died in these fields, forty per cent of the felled by malaria.

Travoys Arriving with Wounded at a Dressing Station at Smol, Macedonia, September 1916 (1918)

While Spencer did not face mortal combat, he was caught up in the maw of the War; and like many men who returned he questioned the meaning and purpose of life, which for him was art. Sounding eerily like Theodore Adorno, he later said, “It is not proper or sensible to expect to paint after such experience.” indeed apart from this commissioned painting of the twinned mules ministering to the needs of the soldiers, Spencer avoided directly addressing the Great War. Many of the artists of the War found appropriate voices, a language the could speak the words of this very modern war, but Spencer served in active duty and did little artistic work during the fighting. But he was storing images and metaphors and memories in his head. The question was one of how to organize these powerful visions. He sublimated his anguish over the war with art that has a subtext of blissful domesticity or thwarted male sexuality, a common post-war theme, or outright refusals of death. But ten years after the war, Spencer got an offer he could not refuse and the result was a chapel in Sandham the walls of which were lined with his experiences in the War. Sometimes called, rather grandly, England’s “Sistine Chapel,” this extraordinary master work will be discussed in the next post.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.