The Willow Tea Rooms

At the University of Glasgow Archive Services, a cramped and spare entry on “Cranston’s Tea Rooms Ltd, reads,

Catherine Cranston owned four tea shops in Glasgow, Scotland, at the beginning of the 20th century. The most famous of these were the Willow Tea Rooms at 217 Sauchihall Street. Completed in 1903, Cranston employed the architect and designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh to design the scheme for the shop. The tea rooms design was inspired by Rossetti’s sonnet “O Ye, all ye that walk in Willow Wood” and which saw art and mysticism wedded to commerce for the first time. Mackintosh remodelled the structure of the building himself, formerly a warehouse, and designed the fixtures, fitting and even the cutlery. The plain white front of the tearooms with chequered border made the shop stand out from its neighbours and the domestic-style leaded windows advertised the intimacy of the interior which was to suggest a willow grove. Spaces were patterns of receding, thin vertical lines using metal screens, wooden panels and the famous tall, ladderback chairs. By 1938, the tea rooms at 43 Argyll Arcade, 28 Buchanan Street, Renfield Street and Queen Street were run by Cranston’s Tea Rooms Ltd . The board of directors consisted of Michael Hook, George Borland and J Adair Mackie. The tea shops themselves were run by a general manager. In May 1950 , the Renfield Street shop was put up for sale and in 1954 the company went into liquidation and were late sold. The Cranston Tearooms, including the Willow Tearooms, were still a feature of Glasgow in 2002.

Willow Tea Room on Sauchiehall Street

The reference to Rossetti was the only artistic thread in the archival entry but it was a poem that inspired the famous Willow Tea Rooms inspired by something as prosaic as an address: Sauchiehall Street where a tea room was located. Because “Haugh” means meadow and “Sauchie” means “a boggy place full of willows,” The Willow Tea Room was named after a poem by Dante Gabriele Rossetti, “The Four Willowwood Sonnets” from The House of Life. The third of the quartet of rather unhappy verses read:

‘O ye, all ye that walk in Willow-wood/That walk with hollow faces burning white/What fathom-depth of soul-struck widowhood/What long, what longer hours, one lifelong night/Ere ye again, who so in vain have wooed/Your last hope lost, who so in vain invite/Your lips to that their unforgotten food/Ere ye, ere ye again shall see the light!/Alas! the bitter banks in Willowwood/With tear-spurge wan, with blood-wort burning red/Alas! if ever such a pillow could/Steep deep the soul in sleep till she were dead, —/Better all life forget her than this thing/That Willowwood should hold her wandering!’

On the right 217 Sauchiehall Street restored

The street name “Sauchiehall” in the old Scottish is a rough translation of “Alley willows.”

Because the Willow Tea Rooms were an oasis of restoration for the inhabitants of Glasgow, both men and women entered the four story building. To guide the visitors to their proper rooms, the different rooms were decorated in the coded colors in which the light or clear colors were designated female” and the dark rooms were for the males. The areas for the men are barely remembered today. But the tea room for ladies was white, silver and pink, the dining room in the back was coated in oak and gray fabric and probably was quite dark, except in the center where he received light lit gallery that was over.The color scheme of the Willow Tea Rooms was lavender and silver, touched with pinks, both deep and soft, scattered over the mirrors and the stained glass windows and doors. The rooms were signifiers of more than gender; the elegance and the colors and the materials employed suggested a certain leisured class, discouraging the lower classes from entering. Working class men would have found the small scaled and somewhat delicate furnishings, designed for immaculately dressed women, physically uncomfortable.

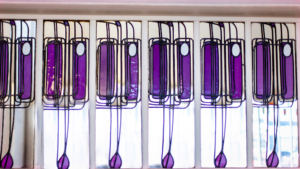

In contrast to the straight lines of the furniture that point to the future, the abstract designs on the glass are curvilinear and very Art Nouveau, even reminiscent of the linear style of Ferdinand Hodler of Switzerland. The mirrors which line the back walls are more like a horizontal dado and carry the stronger colors, while the outfacing floor to ceiling windows are multipaned with long vertical designs that are more geometric. it is these window designs that appear to coordinate with the cutlery crafted for the Tea Rooms. The handles are attenuated and thin with a slight swell along the shaft. The spoon’s bowl and fork’s tine section both have double indents with were the same shapes as appeared on the windows. The accoutrements of the Tea Rooms reiterate themes and motifs at every opportunity, such as the napkins bearing the logo of the establishment. The china upon which tea cakes and sandwiches were served and the tea cups and saucers were patterned with willows.

Mirrored Frieze around the Tea Room

As a total work of art and an all encompassing atmosphere of cool elegance, the Willow Tea Room is a distillation of the design inspirations that shaped Mackintosh. Japan and the long time craze for Japonisme was combined with the unlikely but more local component of Scottish baronial style and the native Celtic design currently being revived. From Japan, which had a strong trading relationship with Glasgow, Mackintosh learned to create an overall atmosphere or ambiance, that mode the furnishings merely a part of the overall plan; from the early Baronial period, he appreciated the simplicity of rectilinear castle construction, and from the Celts, he noticed the tight motifs. The hybrid combination distilled by Mackintosh resulted in his famous chairs, which recall the days when chairs did not recline: they were simply two slabs of wood attached at a ninety degree angle with straight legs attached. In a nod to modernity and to the sensibilities of the female customers who like to sit and talk, Mackintosh put thin cushions on the seats and on the backs, but the ladies were forced to sit upright. In extant photographs these chairs appear pale or perhaps white but the restorations reveal that they were silvered. To relieve the remorseless Medievalism, Mackintosh sliced out the sides of the backs, allowing for a breathing space and punched three rows of three square openings that reiterated the black squares on the sign above the entryway. As if he removed one slice and replaced it elsewhere, Mackintosh added a web shape to the chair legs, with a diagonal rising from back to front. The feet of the chair are dainty and laid back as if they were ballet shoes, ready to dance. The artist achieved a balance between a modern spareness, a Medieval sobriety and regality and a sense of light openness. This same sense of complex spaces and angles and gaps continued on the tables, which have very complex undercarriages and cross bars. The now famous ebonized ladder back chairs cost a mere 17 shillings and six pence when they were originally ordered; in 2014 one chair was auctioned for £109,250.

In an establishment where design and abstraction ruled, there was one prominent painting, the centerpiece of the Room de Luxe, marking the exception that was the rule: Mary Macdonald, artist, former classmate and mate of Mackintosh, produced two moody paintings–gesso panels on the gloomy theme of the “willowwood” poem by Rossetti. Macdonald painted two works of art, The May Queen (1900), for the Cranston tea room on Ingram Street, and O Ye, All Ye that Walk in the Willowwood (1903), created for the Willow Tea Room. The latter was of slightly darker tones and colors than the light lavenders and pinks and whites of the Willow Tea Room. Macdonald was an artist who preferred to develop a dense and more detailed configuration than her husband. The women in her paintings are enveloped in a labyrinth of web line lines, like the drooping leaves and branches of the willow trees reaching down to the bank of the river. There is a moodiness to the Willowwood painting that evokes the poem by Rossetti recalls the original site of the tea room in Glasgow. As Janice Helland wrote in her article, “‘Designful Beauty:’ sensuality, tea and gesso,”

“..Macdonald’s elegantly crafted gesso panels evoke the senses in a place made for eating and drinking, while at the same time, they control the sensuous or, more specifically, they define clearly who regulates sensuality. They complemented an interior that promised warmth and inclusion while, at the same time, they evoked a psychic space for serenity and retreat. They self consciously implied symmetry, order, decorum and refinement..The gesso panel Margaret Macdonald designed for the Willow Tea Rooms evoked a distinctive environment that promised customer satisfaction for those who could afford to enter the modestly priced tea rooms..”

Created for the Sauchiehall Tea Room in 1902

O Ye, All that Walk in Willowood by Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh

The Willow Tea Room was, as is clear from the design and the colors deployed by Mackintosh, a female domain and feminine interior that signified that women could leave the domestic realm and enter into the public spaces where they would be space and preserve their respectability. But as Helland pointed out, the Tea Room was for middle class women who, more than upper class women, needed their own space to gather and actualize themselves. The author quoted contemporary descriptions of the original Tea Room (now restored) and the structure of the Room De Luxe which was above ground level, and the design of the passage to the Room, marked the transition from the male space of the busy street to the protected female environment. “The stairway that led from the ground floor to the tea gallery was designed as a ‘trellised rose-bower’ painted in white, rose and silver. The roof supports were in ‘the form of trees, from which depend the greenish crystal globes of electric light.’ The first floor corridor, ‘decorated in white and silver and white rose,’ had silver lamps hanging from the vaulted ceiling.”

The description of the Room (Salon) de Luxe was gendered and feminized by the local press as if to warn males away. Helland noted that in 1903, the Evening News termed this room “dainty and elegant, the most charming in the house.” The colors, according to The Glasgow Evening News, were “white enamel woodwork, silver silk on the lower part of the walls, purple, silver and white glass, and, opposite the polished steel fireplace with its panel of leaded glass, the centerpiece of the room–the Willowwood panel.” This panel had a place of prominence and was announced and surrounded by a deeply indented white frame the surround of which flared outward as if to enhance and protect its preciousness and uniqueness. The May Queen, with its tripartite grouping had appeared in the 1900 Vienna Secession Exhibition and had been originally made for the Ingram Street Tea Rooms. Perhaps because Macdonald revived the old technique of the gesso panel, the media of the time immediately assumed that it was a female art form, once ancient but now suitable for women. The gessoed panel is the result of a time-consuming process that produced a smooth and hard surface suitable to received very elaborate designs in oils. Macdonald’s surface was overwritten with twine used as lines and enameled glass beads which glittered in the sunlight coming through the wall of windows and bouncing off the mirrors.

In her book, Willow, Alison Syme discussed the funeral theme of the willow in British literature and art. William Morris produced several wallpaper designs on the willow themes that turned a room into a realm of willows which “weep.” Syme argued that Mackintosh and Macdonald took the “willow bower” of Morris and made the tea room in to a stylized version of a willow wood, located at “the house of willows” in Glasgow. She said, “The Mackintoshes imagined the establishment as a willow grove where atmosphere rather than alcoholic beverages would intoxicate patrons. Willows are not directly represented anywhere, but rather evoked through the stylized surroundings. Each chamber had its own decorative scheme in which the theme of the willow was expressed through the repeated shape of the willow leaf, the ‘high spindly backs’ of the chairs, which resembled ‘a forest of young willow trees,’ airy colors and light-dappling mirrors and glass..The heart of the Willow Tea Rooms was the Room de Luxe, a white, grey, silver, pink and purple bower for ladies only. A frieze of vertical mirrors running below the ceiling, inlaid with colored glass and leaf-shaped leading, cast myriad reflections of the slender verticals reiterated throughout the room in the white wooden fillets between the mirrors, the cut outs in the table legs and the tall silvery chair backs. This ‘jewel-like’ sensuous, all-female realm was a kind of ‘gossamer boudoir,’ inviting private reverie in a semi-public space..Mackintosh’s panel depicts three elongated, white-faced women in flowing robes on a pale background. The elegant lines of their raiment, studded with colored glass beads, are difficult to distinguish from these suggesting the pendent tresses of the willows, and the confusion between women and willow is exacerbated by the green ellipse, like a leafy lens, framing the central dryad. One enraptured reviewer described the panel’s ‘star-like,’ ‘mysterious light’ as weaving a veil around ‘the faces and forms of the women walking silently, as if enthralled through the willow grove.’”

The Willow Tea Rooms, a totally planned and completely designed environment for women in the style of the Aesthetic Movement of Scotland was a superb example of an Art Nouveau Gesamtkunstwerk. Like many of the artists of the fin-de-siècle, Charles Rennie Mackintosh combined elements of the past, the curvilinear impulse of Art Nouveau, with intimations of the future, the geometry that would become the hall mark of modern design. As a transitional artist, Mackintosh appears to be less interested in being an innovator and more concerned with creating a Gesamtkunstwerk. However, he was too innovative for Glasgow and rarely received satisfying commissions that allowed him to explore the implications of his unique vision. Beyond the Willow Tea Rooms, one can view his finalized and realized architectural style in the Glasgow School of Art (1897-1909), an expression of the Scottish Baronial style and the more modern Hill House (1902-1904) in Helensburgh, Scotland, built during the time he completed the Willow Tea Room. Like the unbuilt but designed House for an Art Lover, The Tea Rooms were an example of how one small idea blossomed into a fully realized art and design scheme. From a poem written in 1868 by Dante Gabriele Rossetti to a old name of a street evoking a wooded environment that pre-existed the busy port city Mackintosh and his design partner, Mary Macdonald created a refuge for women who wanted to have a lovely afternoon tea in a female paradise of silvers and pinks and lavenders, amid the soft clinks of long handled spoons on china and the gentle sound of tea being poured from the spout of a silver pot.

Original gesso panel flanked by matching coat stands at

Salon de Luxe, Willow Tea Rooms, 1905