War and Glory

From Meissonier to Detaille, Part Two

In attempting to explain and understand the attraction of the French nation to the memory of the recently deposed, defeated and deceased disgraced Emperor Napoléon Ier (1769-1821), the Viscount François-René de Chateaubriand (1768–1848), wrote in his Memoirs from Beyond the Grave (1848-50),

“One asks oneself by means of what influence Bonaparte, so aristocratic, such an enemy of the people, came to win the popularity he enjoyed: since that forger of yokes has assuredly remained popular with a nation whose pretension it was to raise altars to liberty and equality; this is the solution to the enigma: Daily experience shows that the French are instinctively attracted to power; they have no love for freedom; equality alone is their idol. Now, equality and tyranny are secretly connected. In those two respects, Napoleon took his origin from a source in the hearts of the French, militarily inclined towards power, democratically enamoured of the levelling process. Mounting the throne, he seated the people there too; a proletarian king, he humiliated kings and nobles in his ante-chambers; he levelled social ranks not by lowering them, but by elevating them: levelling down would have pleased plebeian envy more, levelling up was more flattering to its pride. French vanity was inflated too by the superiority Bonaparte gave us to the rest of Europe; another cause of Napoleon’s popularity stemmed from the confinement of his last days. After his death, as people became better acquainted with what he had endured on St Helena, they began to pity him; they forgot his tyranny, remembering only that after first conquering our enemies, and subsequently drawing them into France, he had defended us from them; today we conceive that he might have saved us from the disgrace into which we have sunk: we were reminded by his misfortune of his fame; his glory profited by his adversity.”

Chateaubriand would be amazed to learn that, even today, the cult of Napoléon has some purchase on the world’s imagination. But, the decades after his nephew Louis Napoléon (1808-1873), the second Emperor of the Second Empire ill-considered war against Prussia ended in the decisive defeat of France, the decisive rise in power of Prussia, and the emotional exhaustion of the nation were difficult for military artists. But Jean-Louis Ernest Meissonier (1815-1891) and his pupils carried on with the tradition, revived under Napoléon III and newly popular.

By 1860, nearly a decade into the Emperor’s reign, five years after the unfortunate Crimean War, Meissonier followed his seminal painting of Napoléon’s defeat in 1814, Campaign of France, 1814, with a more optimistic study of war, featuring his nephew, who was attempting to be a military leader in his own right. This work featured Napoléon III at Solferino. In 1882, one of Meissonier’s early biographers, John William Mollett, recorded that in the late 1850s, “M. Meissonier was much noticed by the Emperor, and we read in the Gazette des Beaux Arts of September 1859, that he was at that time just finishing the sketch of The Battle of Solferini; and had received a commission for another historical picture of the meeting of the two Emperors of France and Austria, on horseback; and was about th return to Italy to take the sketch on the precise spot where this historic incident occurred..” By 1864 both paintings were finally completed. The two paintings were shown together in the Salon of 1864, the Salon that followed the death of Delacroix and the end of the Romantic era. As early as 1864, these two paintings were considered to be the highlights of Meissonier’s Napoléonic paintings so far, and yet Salon politics denied a medal to Meissonier. Rather than give a medal to a mere genre artist, the jury decided to not award a medal at all that year to an artist who painted small pictures. The art critic Édmond About praised the pair of paintings and contrasted the new Emperor with the old Emperor. “Look at the Emperor at Solferino. The principal personage, posted in front of his staff, is looking on at the battle as a cool player studies a chess-board. A score of officers around him, all like himself on horseback, are waiting his orders..Now having studied this familiar victory presentée sans emphase–recross the room and look at the Retreat of 1814. It hangs exactly opposite to make an antithesis. It is also a picture of a general staff, but of a staff in defeat. Napoleon conquered, but firm and resigned, is at the head of a group of the generals and marshals of France. His fine head is crowned with that ‘auréole de malheur‘ which outlives all other crowns in history..”

Ernest Meissonier. Napoleon III at the Battle of Solferino (1863)

Unmentioned in the praise for this painting were the consequences of this battle. Remembered chiefly as the alliance of France and Sardinia against an old enemy, Austria, for the purpose of pushing them out of the territories that would become modern Italy, the Battle of Solferino could have been, in the mind of the Emperor, payback for the defeat depicted by Campaign. Whatever the reason for participating in a war that had little to do with France, the Emperor’s new conflict was a costly one. The causalities of the battle (June 24, 1859) were huge. Forty thousand wounded and dying men were left helpless, without medical help and were forced to stumble to the nearby village of Castiglione, seeking help. One would have thought that the French would have learned the lessons of the Crimean War and the good work done by Florence Nightingale and her nurses, but not until the American Civil War would any army have more doctors than veterinarians. A Swiss businessman who was passing through the village paused to help the women and later called the carnage a “disaster on a European scale.” Henri Dunant (1828-1910) later published A Memory of Solferino in 1862, calling for the formation of nurses and orderlies trained in battle and within a year the International Red Cross had been formed. But before the Red Cross was established, those who died in battle was neither gathered up nor were they buried in a timely manner by the combat nations. That sad task was customarily left for those who lived in the area. In the environs of Solferino, the bodies of the dead were looted by humans, then picked at by birds, rotted and decomposed before they were finally buried.

The battle, presided over by Napoléon III and Victor Emmanuel II, was hardly glorious or decisive. Despite having an excellent army, the French leaders made a series of mistakes and early reports of victory soon turned sour at home as reports of the heavy losses arrived. The Mémoires du Comte Horace de Viel Castel reported that people demanded an end to the Italian campaign: “this war is abominable; it is time for the Emperor to put an end to it, we do not need a second campaign or a second war bond.” Aside from public unrest brewing, it was the overall heavy casualties–the loss of 90,000 troops and the huge number on a single day, horrifying Durant–that actually won the day, forcing Napoléon to seek a truce with the Austrians. The deal between the French and the Austrians turned Lombardy over to the French, which then gave the territory to the Italians. Having defeated the Austrians, French honor was apparently satisfied and the Emperor went on with his career, leaving the Italians feeling betrayed and forced to fight for the rest of their country alone and on their own.

In retrospect, it seems that Meissonier might have suffered from a condition that we today would called OCD or obsessive-compulsive disorder. How else can one understand the fact that it took the painter fifteen years to complete his second and final effort on his proposed series of five? The work 1807, Friedland finally appeared in 1875, five years after the Second Empire had collapsed and the nephew of the main character in the military drama was in exile in England, back where he started. Meissonier probably reached his career in 1867, when he won eight grand prizes for his fourteen paintings at the International Exposition in Paris and, in the same year, he was awarded a Legion of Honor. This was the same year as the execution of an Archduke of Austria, Maximilian, whom Napoléon III had attempted to install on the “throne” of Mexico as “emperor.” Three years later, the Second Empire and its un-artful and disastrous foreign policy came to an ignominious end, when the Emperor allowed himself to be unwisely drawn into a conflict with Prussia. A military man who had served in the army early in his life, Meissonier was attached to Emperor’s army as a colonel and the painter actually joined Napoléon on his final folly and narrowly missed being captured by the Prussians near Metz. The Franco-Prussian War and the Siege of Paris, for all intents and purposes, put an end to the Cult of Napoléon, and forced the French to face the consequences of modern war.

Meissonier had been working on a triumphal painting, 1807, Friedland, for so long that its execution spanned the peak of the Second Empire to the bitter aftermath and defeat after the Franco-Prussian War. This belated painting retains the old spirit of the past, clinging to the naïve belief of the greatness of an individual who put his pride and ambition before the benefit of his nation. Napoléon’s desire to be a Roman style conquerer delayed the entry of France into the modern world of the nineteenth century, ultimately costing the nation dearly, diminishing its place in the world. The painting which capped the career of Meissonier lacked criticality, but it was typical of its time. For Meissonier, this was a large painting, over 53 inches wide, and 1807, Friedland celebrated one of Napoléon’s victories over the Russians in the glory days of his regime. Typical of his practice, Meissonier made hundreds of sketches and asked a group of calvary officers to ride through grain fields, similar to those in Russia, studied the results and incorporated the trampled stalks in the foreground. “I did not intend to paint a battle; I wanted to paint Napoléon at the zenith of his glory; I wanted to paint the love, the adoration of the soldiers for the great captain in whom they had faith and for whom they’re ready to die..it seemed to me that I could not find colors sufficiently dazzling. No shade should be upon the emperor’s face to take from him the epic character I wished to give him.”

Ernest Meissonier. 1807, Friedland (1875)

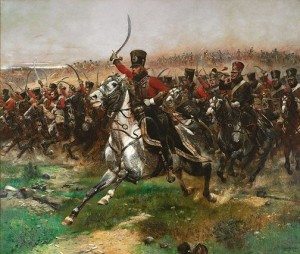

We see the echoes of the dashing and exciting Friedland, somewhat uncharacteristic of the staid Meissionier, in a painting by his pupil Édouard Detaille (1848-1912), Vive L’Empereur (1891), also known as Charge of the 4th Hussars at the battle of Friedland, 14 June 1807. Oddly, this painting suffered a fate similar to that of 1807, Friedland in that it was purchased by a non-French buyer and disappears from French eyes. The American Alexander T. Stewart paid $60,000 for a painting he had never seen and today the work described by Henry James as one of “the highest prizes in the game of civilization” is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. While the fact that Detaille’s painting was as eagerly purchased suggests that the Cult of Napoléon still had power, the fate of Vive L’Empereur (1891) was less fortunate. The art gallery of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia paid 3,000 pounds for the Detaille, which was received with great excitement, but at some point between 1893 and the 1930s, the painting seems to have fallen from favor, was only intermittently exhibited, and in 1959 was damaged by water when it was in storage. But, presumably to a recent restoration of respect for and interest in late nineteenth century French academic art, funds were raised to restore the painting which is now hanging next to Alphonse de Neuville (1835-1885), Detaille’s painting partner, The Defense of Rorke’s Drift, 1879 (1880).

Édouard Detaille. Vive L’Empereur (1891)

Alphonse de Neuville. The Defense of Rorke’s Drift, 1879 (1880)

The two paintings provide an interesting contrast, and, in that contrast, present the story of French politics and culture after the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871). Vive L’Empereur (1891) looks back to the safe past, a time when France ruled Europe and Napoléon dominated the thoughts and futures of its inhabitants for the sixteen years of his rule. The other painting, despite its European sounding-name–“Rorke’s Drift,” is a dramatic retelling of a colonial war of imperialism–not French–but English, and the battle was fought in South Africa. The combatants are not the French and the Russians but the English and the Zulus, and it unclear precisely why de Neuville selected the incident. But, regardless of its possible intentions, the scene is cinematic and jingoistic, echoing the European attitude towards empire: the right of the white men to rule the dark men and the willingness to fight for imperial goals. More importantly, if one was a military painter in France, the days of Napoléon are long past and military glory, if there is any to be had, must be found through the Empire, and in 188o, the French were not in the game. The paintings by de Neuville and Detaille were conceived during what would be a long period of peace in a Europe freed of all Napoléons. The exciting battles had moved to other continents, saluting colonial contests. Only in 1881 was the Third Republic willing to enter into the expensive effort of empire-building by occupying Tunis, but de Neuville, how died in 1885 would not live to see the renewal of French glory. Even though by the beginning of the twentieth century, France became the second largest empire, eclipsing Germany, the Republic was haunted by the shameful defeat of the Franco-Prussian War. The final post in this sequence on the nineteenth century will discuss the joint project of Meissonier’s two pupils, a gigantic panorama which dared to take up that delicate topic of the Franco-Prussian War.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.