Walter Richard Sickert (1860-1942)

Part Two

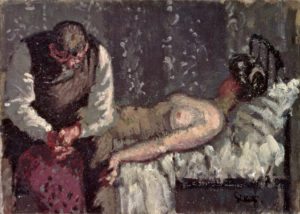

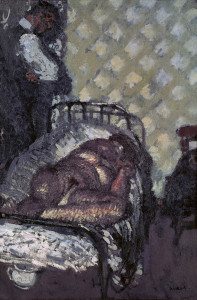

In 1911, Walter Sickert was the leader of a small but hopeful group of young male artists in London, including August John, Lucien Pissarro, Henry Lamb, who wanted to make art outside of the confines of the Royal Academy. Although the middle aged painter seemed an odd choice as a Pied Piper, he had spent much of his career in France and would be assumed to know the most recent trends in Paris. But the proposition was a good one: Sickert, a failed actor who had become a painter, was backed by James Abbot McNeill Whistler and knew Edgar Degas, so his artistic ancestry was impeachable. In the early twentieth-century, Fauvism had come and gone and Cubism was a very new movement, lacking any clear direction, while in London itself, the city was still reeling from the shock of encountering Roger Fry’s seminal exhibition Manet and Post-Impressionism at the Grafton Galleries in 1910. So when Walter Sickert’s very Degas-esque paintings of female nudes were exhibited at the Carfax Gallery in 1911 and 1912, the viewers would have seen a new Post-Impressionistic version of the modern “problem” picture, as pioneered by the Pre-Raphaelites. The focal point of these exhibitions was Sickert’s rendering of or response to a notorious killing, later known as the “Camden Town Murder,” in a house close to his own neighborhood. The trio of roughly painted scumbled canvases were crude and seem to have been hastily painted or painted under the influence of strong emotions. As if the artist was caught up in an obsessive repetition, all works showed a woman lying still on a skimpy bed presided over by a male companion or onlooker or observer. The paintings were ambiguous in content, and the curator and critic, Roger Fry, taking a page from the formalist book of Emile Zola, reviewed the paintings from a distance–as works of art, not as works of reportage, much in the same way the French novelist had viewed Manet’s Olympia (Salon des Refusées 1863). The Great War broke out a few years later, extinguishing the brief sensation of the murder; and for almost a hundred years, the Camden Town paintings which may or may not have been about an obscure murder, fell into obscurity.

Walter Richard Sickert

The Camden Town Murder or What Shall We Do about the Rent? (c.1908)

But in the beginning of the twentieth century, the nearly forgotten artist, Walter Sickert, a painter who was too old for the new century, was suddenly resurrected. This new fame for a forgotten painter exploded when, to the astonishment of the world of British art, crime writer Patricia Cornwell published a book in 2002, Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper–Case Closed. Using art by Sickert as evidence of his crime, she announced that Jack the Ripper was none other than the artist. The idea that Walter Sickert was a murderer never gained any credence beyond the strange world of Ripperologists. The venerable art critic for The Guardian, Jonathan Jones, was more amused than impressed with Cornwell’s devotion to the case.

Crime novelist Patricia Cornwell has bought no fewer than 32 of Sickert’s paintings in her quest to prove he was the serial killer who terrorised late 19th-century Whitechapel. Cornwell claims she now has crucial evidence, including watermarks on letters, that puts Sickert in the frame as London’s most notorious murderer. She’s not the first Ripperologist to take an interest in him: Sickert also appears in Alan Moore’s graphic novel about the case, From Hell. But no one else has bought up a load of his paintings, taking them out of the public eye to use as “scientific” evidence, or spent more than a decade trying to put him, posthumously, in the noose. A noose it is, for Cornwell’s accusation burns out Sickert’s real achievements and irradiates him as an artist. Here is a bold painter who was not afraid to put sex and sleaze into his art at a time when most British artists were timid and repressed. He dares the radical urban danger that artists in Paris were so alive to. Why does that make him a likely serial killer? Ripperologists are the last Victorian prudes, associating sex and evil.

Walter Sickert. L’Affaire de Camden Town (1909)

Cornwell herself stated that it was only years after Sickert painted his three paintings, which may or may not have been in response to the Camden Town murder, that a vital clue emerged. In 1937, it was reported that Sickert was allowed inside the room where the woman was murdered and was permitted to sketch the body. Cornwell wrote,

So he just happened to show up at the crime scene before the body was removed and innocently asked if he might have a look inside and do a few sketches. Sickert was the local artist, a charming fellow I doubt the police would have refused him his request. They probably told him all about the crime.

She also noted that his visit to the crime scene would have provided an explanation of why his fingerprints appeared at the crime scene and came to the conclusion that he had deliberately inserted himself into the crime scene. Assuming that the revelation that the artist was present at the murder scene is correct, then the topic of the three Camden Town paintings seems to be that of the artist himself viewing the body of the murdered woman in preparation for the later paintings. If the hypothesis of Cornwell is true, then Sickert was a remarkably calm murderer. In 1934, he casually shrugged off the role of murder in his art:

It is said that we are a great literary nation but we really don’t care about literature, we like films and we like a good murder. If there is not a murder about every day they put one in. They have put in every murder which has occurred during the past ten years again, even the Camden Town murder. Not that I am against that because I once painted a whole series about the Camden Town murder, and after all murder is as good a subject as any other.

Cornell was not the first writer to link Sickert to the Jack the Ripper murders. Amazingly there were two earlier books, each insisting upon a connection. In 1976 Stephen Knight claimed the Sickert had been forced to be an accomplice to the murders. This dubious theory, appearing in his book, Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution, came from a man who claimed to be the artist’s illegitimate son, who later confessed to lying. This in-credible source was followed almost twenty years later by still another book by Jean Overton Fuller, Sickert and the Ripper Crimes, came to the conclusion in 1990 that Sickert himself was the killer. Fuller believed, based on gossip passed from her grandmother to her mother, that Sickert’s paintings of Camden Town and it’s murder contained clues concerning Jack the Ripper. While both books are purely speculative and rehash a century’s old stew of sensationalism, Knight’s book is remembered best, because it became the basis for the Johnny Depp film, From Hell (2001), which presented a complicate conspiracy involving the royal family and Masons, mad murders, plural, and helpless victims, also plural.

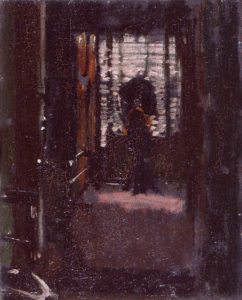

Writing a decade after Cornwell’s sensational book, Lisa Tickner’s well researched essay, “Walter Sickert: The Camden Town Murder and Tabloid Crime,” for the Tate museum puts the artist’s paintings in the context of the art world at the time and locates them in the site of the public lingering fascination with lustmord and with all things Ripper. As Sickert’s painting, recording the dark and brooding bedroom of Jack the Ripper attests, the artist was as interested in the notorious murders as the general public. He had been told by his landlady that he was living in the Jack the Ripper bedroom and may have believed her, but the story, true or not, provided him with a sensationalized painting.

Walter Sickert. Jack the Ripper’s Bedroom (1909)

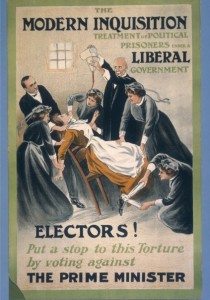

Most of the many articles on Sickert’s obsession with nude women, models or prostitutes, alive or dead, do not draw a connection between the social events of the era, but those years at the turn of the century were those of the Suffragette movement. In 1906 the leaders moved their headquarters to London, which became the launching pad for a political crusade that was remarkable for the violence that broke out between the genders. The Women’s Social and Political Union was a militant group that believed in deeds over words, and a year before SIckert painted the Camden Town works, three hundred thousand people, men and women, marched through the streets of London in the Women’s Sunday Procession in June 1908. The years before the Great War witnessed women going to prison for their rights as citizens and being treated brutally. Once incarcerated, the women continued their protests against arbitrary male authority and refused to eat. Faced with women willing to die for the vote, the jailers tortured the women with force feeding. Not all survived the ordeal.

It is absurd to take seriously the notion that an overweight, middle-aged artist would slash a woman’s throat and then sketch his own bloody deed. But the male attitude towards women, whether played out on canvas or in political violence on public streets or in prisons, was proprietary and contemptuous. Although Sickert was a man of his own time, he was hardly unique in his patronizing attitude towards women. One can note a correlation between a public fascination for depictions of lustmord, the crime of passion, a man stabbing a woman, that emerge when women begin to demand their civil rights and to take control of their own lives and their own bodies. The lustmord paintings reappeared in Berlin, after the Great War, when women were emancipated from the antiquated customs of the nineteenth century. In our own time, popular culture, from films to television, portrays women as being murdered by so many serial killers so often that, at a time when women are running for and winning political office, it is a wonder that any adult woman is left alive. Clearly something like fear of change and a dread of losing dominance plays out in the culture and is expressed through violence against women, whether depicted in art or enacted in real life.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.