Stanley Spencer (1891-1959)

The Artist at Sandham

Part Two

Unlike many artists of the Great War, Stanley Spencer remained silent and refused to translate his experiences into paint. His reticence as an artist, while unusual, can be explained in part by the fact that, unlike his colleagues from the Slade School of Art, Spencer was never an official war artist. And, his silence was typical of many veterans in that war and in other wars–there are simple no temperate or socially acceptable words to describe the sights and smells and sounds of the first modern war, a war that still defies full explanation. After a decade of muteness, Spencer painted his experiences on both fronts, the home front hospital at Bristol and the far away campaign in Macedonia, combining memories of caring for soldiers at the military hospital with those of being on active duty in Macedonia on a singular memorial for a single soldier. The result was a cycle of paintings at an secluded family chapel, tucked away in the English countryside, a body of work often forgotten but sometimes celebrated and recently rediscovered. According to Paul Gough, in his 2007 book, Stanley Spencer: Journey to Burghclere, five years after the War, the artist was approached by the Sandham family and given a commission dedicated to remembering a fallen son. For five years, Gough states, the artist (rather like Michelangelo) worked on scaffolds in the tiny chapel, and Spencer produced an astonishingly original and un-categorizable commentary, not so much about the War itself, but on the theme of healing, cleansing, and, finally, rising from the dead.

Fighting and dying is never directly addressed in the murals. The paintings are dedicated to the peace that can emerge from War, the peace that comes from contentedly taking care of the basic necessities of life itself. Although Spencer had served in Macedonia as an ordinary soldier, experiencing what was apparently the inevitable life in a trench, sunk in the ancient ground of Alexander the Great, active conflict is banished. The decision is an interesting one, for the young Sandham died in a worthy cause. This fight, an age old one, between Greece and the Ottoman Empire, was a nasty appendage to the War, but it was critical and crucial to pushing the teetering Empire out of the War. Towards the end of the long campaign, at the end of the War, the fighting was fierce and deadly and the causalities were high, but Spencer survived. After repeated bouts of malaria, Spencer was sent home, but in 1919, as if he had been stalked by death, another veteran of this difficult campaign, Lieutenant Henry Willoughby Sandham, succumbed to the same illness–the all pervasive malaria–that had overtaken him in Macedonia. His grieving family built a private chapel to his memory at Burghclere in Hampshire and asked Spencer, who was familiar with the Macedonian front, to provide a series of paintings for the Chapel. It is here, as with the painting of the Travoys, that the memories of two wartime experiences are meshed and woven into a suite of paintings inspired by Giotto’s Arena Chapel. “What ho, Giotto,” Spencer explained in typical British fashion when he was offered the commission.

The family chose well. None of Spencer’s fellow artists were both familiar with the Eastern Front and based their art on the Early Renaissance. The paintings are solemn and frozen in time, lacking the perspective of the late Renaissance. Spencer used the primitive perspective of the Early Renaissance, allowing the artist to balance reality and miracles, the mundane and the sacred in the same work. Consecrated in 1927, the Sandham Memorial Chapel itself is at best modest or undistinguished or at worst entirely uninspired and unworthy of its contents, but is the only building owned by the National Trust devoted to memorializing the Great War. The nineteen paintings by Spencer, executed to the fugues of Bach, have been called “neglected masterpieces” that inspired a “rebirth of British painting” by the British Masters series.

The tiny chapel should be thought of as an enclosure for a series of altarpieces: vertical paintings with gothic arch and horizontal paintings which are the predellas for these multiple polyptychs. The segments of the polyptych are separated by modern wainscoting painted clean and simple white. The upper paintings are about Macedonia and the predella is about the chores carried out in the hospital in Bristol. Although the assemblage is an homage to Giotto, the paintings are not frescoes but oils. Sadly, the chapel is tucked away and does not attract the visitors it deserves, so it was especially welcome, when, in 2013, the paintings were removed for the first time to be exhibited at London’s Somerset House. Two Macedonia scenes were bonded to the wall and could not be moved.

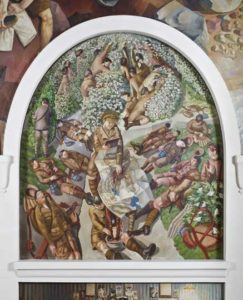

Stanley Spencer. The Resurrection (1932)

Like the Arena Chapel, the climatic event in Sandham Chapel is the Resurrection, a favorite theme for Spencer, one that would linger long after the war was over. Twenty-one feet high, the Resurrection, which took Spencer two years to compete, is a complicated and multifaceted final reckoning for the soldiers who were sacrificed and who must be saved and rewarded in heaven. Like the Arena Chapel, the series of paintings that align the facing walls of the Chapel are about life, not of Jesus, but scenes in the Military Hospital in Bristol where magically the stricken soldier of Macedonia are transported as their final destination. At the end of the long journey is peace. The overriding concept for the entire cycle is that of quietude: the site is the Hospital, the scenes are set in nondescript rooms where ordinary, mundane tasks must be carried out in order for existence to continue. The soldiers take care of each other, in solemn silence, all animation suppressed, expressions subdued. Everyone exists in a self-sufficient state of absorption. All energies, of the men, wounded and recovering, are directed towards healing as they strive towards health and recovery and finally release.

Spencer’s concern was with preserving life, through repetitious tasks, which give hope that life will go on. Fresh from the Front and its constant dangers, the minds of the soldiers come to rest and through this rest, they will adjust to the unexpected peace. It is the simple labors of orderlies and recovering soldiers engaged in cleaning the hospital, feeding the hungry, caring of the sick–all the basic jobs of living–this is what it means to survive and heal. To unearth the sub-text, this healing labor is what Jesus did when he was alive, providing succor and sharing simple food with his followers. There is a comforting scene of a British tea, or mid afternoon snack: steaming cups of Earl Gray, stacked slices of buttered bread spread with red jam, carefully prepared for the wounded by the ambulatory, that rises to the level of the serene. Wiped clean of hustle and bustle, this is an old fashioned and simple nursery tea, a welcomed reminder of childhood safety, house and home. For a soldier fresh off the front, such a basic gesture of civilization, sharing humble buttered bread would have been a slice of heaven, made all the more miraculous coating of fruit jam. Spencer inserted himself among the contemplative tea makers, by asking them to make his favorite food, buttered bread as an offering to the wounded.

Stanley Spencer. Tea in the Hospital Ward

The story begins with the soldiers arriving at the Bristol hospital in a convoy of wounded and ends the the dead–mules, soldiers, old friends–reunited at last and rising from their cross studded graves, defying the death toll that had engulfed Henry Sandham. Jesus is present for the Resurrection, but he is a modest figure, as he was in real life. He helps the soldiers to glory, mirroring the tasks and jobs undertaken by the hospital support staff in the flanking paintings.

One enters and reads the walls as if one would read a book, and yet it is quite possible to become absorbed in each painting. The self-contained scenes re-remembered by Spencer are always of cleansing, as if to wash away the memories of war, of making order out of chaos, of keeping control, using the beauty of the ordinary and, out of it, finding something sublime in the humble. From the meticulous murals, thick with detail, we learn that soldiers lived under mosquito nets in Macedonia, only to emerge from their coverings to become stricken with malaria. We learn that hospital walls were covered with photographs and mementos tacked up by the residents, who seem to be making a road map towards home.

Detail of Bed Making

One of the odder recurring details is the luxurious presence of rhododendron, appearing at the Bristol hospital and reappearing in Macedonia. Almost certainly the flowers are symbolic, signifying new life, spring and blossoming, a promise of future heath. But as Jane Brown pointed out in her 2004 book, Ravishing Rhododendrons and Their Travels Around the World, “Most of the early rhododendron men were medics. Their botany was learnt as part of their medical training.”

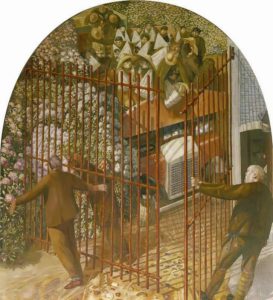

Stanley Spencer. Convoy Arriving with the Wounded

Interpretation of the flowers in Spencer’s paintings are hard to come by, but the information I have put together makes a connection between rhododendron and healing. The rhododendron is no ordinary flower. Brown continued to discuss Christian Friedrich Samuel Hahnemann, who interestingly enough, developed a cure for malaria out of quinine extracted from cinchona bark. Malaria was, of course the illness that sent Spencer home and the eventually killed Sandham. Hahnemann’s book, The Encyclopedia of Pure Medicine–A Record of the Positive effects of Drugs upon the Healthy Human Organism, was published in America in 1879. The early study on homeopathic medicine, “contained tightly printed pages of proving of a tinctue of the Russian intoxicant and anti-rheumatic ‘yellow rosebay,’ Rhododendron chrisanthemum. It is immediately clear that this is a powerful drug..” Brown wrote.

Stanley Spencer. Map Reading

The flower’s name comes from the Greek rhodo, rose, and dendron, tree and, yes, this healing flower is a deadly drug. According to Walter Mangor in the Journal American Rhododendron Society, “The earliest record of rhododendrons comes from the disaster which befell the army of Xenophon, retreating from Babylon in 401 B.C., which camped in the Armenian hills inland from Trebizond on the Black Sea coast of Turkey. The starving soldiers consumed large quantities of honey made from the poisonous nectar of the yellow flowered Pontic Azalea, Rhododendron luteum, and were overcome by nausea and vomiting. A similar disaster affected the army of Pompey in the same area in his campaign against King Mithridates of Pontus in 66 B.C. and also the army of Alexander the Great of Macedonia on his way to India in 327 B.C.”

Here in the area of the Balkans where the Macedonia front was located, grow this very toxic and very hallucinating variety of flower, which, as can be seen, was notorious throughout history. As Emma Bryce wrote in her article, “The Strange History of ‘Mad Honey,” “Rhododendron flowers occur all over the world, and yet mad honey is most common in the region fringing the Black Sea — the biggest honey-producing region in Turkey..In Turkey, not only do the poisonous rhododendrons abound, but the humid, mountainous slopes around the Black Sea provide the perfect habitat for these flowers to grow in monocrop-like swaths. When bees make honey in these fields, no other nectars get mixed in — and the result is deli bal, potent and pure.” As dangerous as its after effects, rhododendron is known to have positive medicinal qualities. Bryce quoted Salesman Turedi, who said, “People believe that this honey is a kind of medicine. They use it to treat hypertension, diabetes mellitus and some different stomach diseases.” The presence of the flowers is so pervasive, their glorious blossoming cannot be an accident. Spencer served in the Balkans and there is every reason to assume that he would have known the local reputation of rhododendron as having certain healing qualities. How delighted he must have been to discover the same flower (different species) at Sandham and he made them bloom with healing hope, planting them in every probable site–at the hospital gate–and improbable site–a soldiers’ camp in Macedonia.

The paintings in the Chapel was unique in the annals of art of the Great War in that they focus on an often unacknowledged aspect of battle: the aftermath. The topic of recovery and the services the soldiers received was usually taken up during the War by official artists, directed by the government to provide that particular type of information to the public. In contrast to the public nature of much of the art of the War, whether through gallery exhibitions or government propaganda, Stanley Spencer labored five years on a major contribution to British art that was private and contemplative. Within the memorial setting is an encyclopedia of a time of transition from the battlefields to the hospital and then–bypassing actual death–to a sublime resurrection with Jesus on hand to assist the fallen men and the patient beasts along the rest of their journey, presumably to God.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.