The First Twin Towers–The Chrysler Building (1930)

and the Empire State Building (1931)

The Empire State Building: Part One

Like the clouds of fog hovering around its spire, the Empire State Building is shrouded in myth, lore, and legend. Design-wise, it is an undistinguished building, a typical skyscraper built for corporate purposes under the guidance of William F. Lamb (1893-1952), a member of an architectural firm, Shreve, Lamb and Harmon Associates. The most significant aspect of the Empire State Building is that it was tall for its time and that it was engaged in a race to the top with the Chrysler Building at the beginning of the Depression decade. The extent of the frantic efforts to add height can be read by the almost hasty stacking of tier upon tier, following the rules of the “set-back” law used to gain height. Its rival structure also climbing up in the clouds, the Chrysler Building, was a much more graceful building, designed with wit and elegance by William Van Alen (1883-1954). When it was completed, the Chrysler Building lost the race to be tall but it is remembered and cherished because the crown is a tribute to the automobile–a mixing of metaphors–and the Crystler Corporation’s homage to chrome. While it could be argued that between the two, the Crystler Building is, for a skyscraper, is quite beautiful, it is the Empire State Building that–as if to make up for its lack of design–clad itself in stories and gained the greater fame.

E

E

Evan Joseph photograph of the original twin towers

When most of us first saw the Empire State Building, it was being climbed by King Kong in the excellent original version of the love affair between a giant ape and a beautiful blonde. King Kong had a tragic ending when the beast battled tiny airplanes zooming around him like pesky bees, and then sacrificed himself to protect Fay Wray. Kong’s fatal plunge off the Empire State Building linked the world’s tallest building (at that time) with love and death. We revisited the building, again via the movies, and again on cable television where old movies live on, when we waited for An Affair to Remember to come to the required happy ending. That film had an all human cast but, due to an untimely accident, the humans missed a romantic rendezvous at the top of the Empire State Building and it was years before they were reunited. Thanks to such early films, Sleepless in Seattle, with Meg Ryan and Tom Hanks, rekindled memories of Cary Grant and Deborah Kerr and lit up the eighties with the sentimental belief that one could meet one’s true love at the Empire State Building. Today, the Empire State Building is the destination for people who want to meet cute or get married. But there is a dark side to the Building: it is also, like any edifice that is tall and famous, a spectacular place from which to commit suicide.

King Kong on the Empire State Building

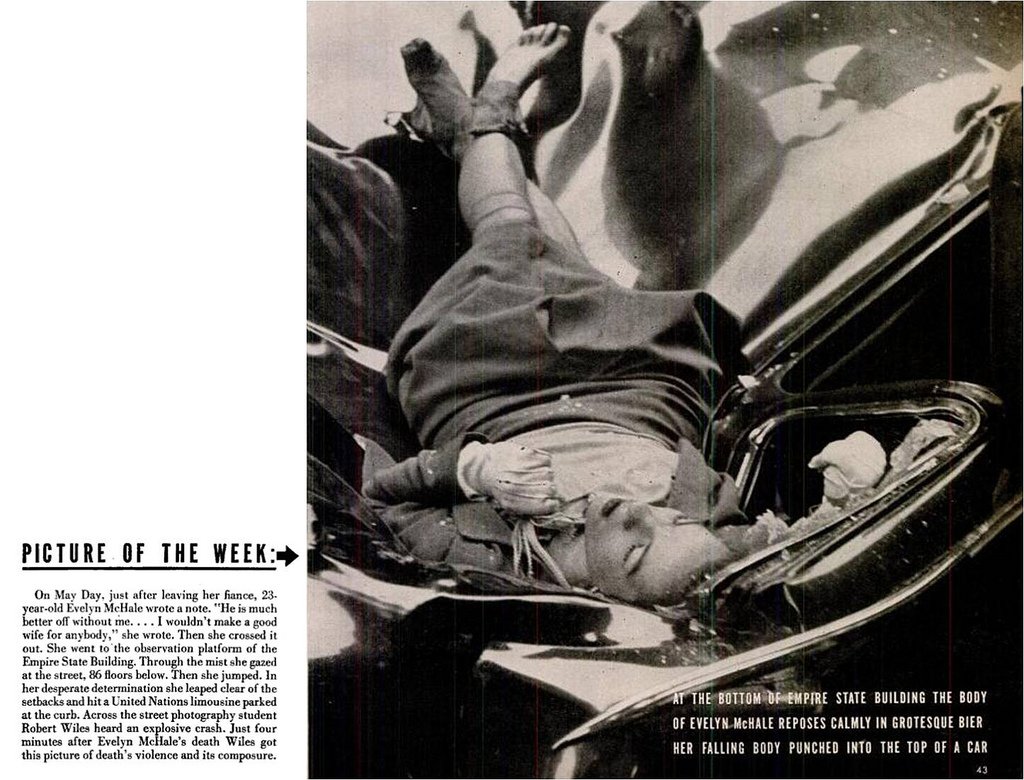

Thirty people have managed to elude security guards and safety precautions and jump to their deaths. The last death was in 2006 but the most famous was that of the beautiful Evelyn McHale who decided to die rather than marry a man she did not love and jumped in May of 1947. Although her “story” was dryly told in an article in The New York Times, McHale remains famous in the art world because she was beautiful and her beauty was not marred by her fall from the 86th story observation deck. Well dressed and tidy, she had folded her coat neatly and left it behind when she climbed over the railing. Her white scarf followed her over the side, floating gently on the windy currents that swirled around the building., Becuase of its many elaborate set-backs or outcroppings in the upper stories, the Empire State Building was a notoriously difficult building to jump from. One would-be suicide was even blown back in place by a gust of wind. Other attempts were thwarted by premature landings on a roof a few stories below. But Evelyn McHale managed to clear all the obstacles. She landed neatly on her back, indenting the roof of what is described as “a United Nations Assembly Cadillac limousine,” parked on 34th street. Her legs were neatly crossed at the ankles. Although the fall ripped her stockings from her thighs, pushing them down over her calves, the short gloves on her hands remained perfectly white. Her face was perfectly made up, lipstick dark and curved into a peaceful smile, eyes lightly mascaraed and closes, darkened brows smooth in death. She died like a lady, oddly clutching her pearls.

We know all these details thanks to a young photographer student, Robert C. Wiles, who got the shot of his life. This famous image wound up in Life Magazine, an unusual picture for a family magazine. The caption stated, “At the bottom of the Empire State Building the body of Evelyn McHale reposes calmly in grotesque bier, her falling body punched into the top of a car.“ It was here, in Life Magazine, that a young artist, Andy Warhol, found it and used it years later for his Death and Disaster Series of the 1960s. The Warhol photo silkscreen, variously titled Suicide (Fallen Body) or 1947 White of 1963 re-presents the original photograph, reprinted in Life, either as a single image or repeated in a grid across a large canvas. Warhol, famously indifferent to tragedy and to death, both of which he defined as random, gazed upon the meaningless deaths with a shrug, a tribute music video appeared on YouTube in 2013, recreating the suicide, white scarf and all, shows the fascination with the nexus between love and death and the Empire State Building.

Andy Warhol Suicide (Fallen Body) (1963)

Paradoxically, both the Chrysler and Empire State buildings were planned during the Jazz Age, the Roaring Twenties, when money seemed to be flowing without end, but they were built when the fun ran out and a gray gloom descended upon Manhattan Island. One might think with the Crash happening a mere year ago that investors might have waited before embarking on a huge construction project, much less with two, but Depression aside, these buildings were the products of two egos of two powerful men who decided to race each other for the tallest building in the world. John Jakob Raskob of General Motors could not allow Walter Chrysler of the Chrysler Corporation to out build him and claim the prize. The Empire State Building, its design supposedly inspired by the shape of a pencil, was constructed in a year, under the collective eyes of delighted New Yorkers. Hundreds of construction workers, photographed by Lewis Hine, were given jobs, dangerous jobs to be sure, but jobs at a time where employment had risen to 25%. It is perhaps with Hine, and his extraordinary suite of photographs chronicling the rapid rise of the building that began the discourse on the legend of the tallest structure on earth. Tall as it was when it came to the design and sheer style, the Empire State Building was outdone by the (barely shorter) Chrysler Building.

Lewis Hine. Welders on the Empire State Building (1930)

Lewis Hine. Welders on the Empire State Building (1930)

Upon completion, the Crystler Building seemed to preen like a peacock spreading out its metallic crown in a starburst of pride, while the Empire State Building was more somber in its dour façade, perhaps more suitable for the Depression. Both buildings, however, were the products of optimism and aspiration. None of the dreams of lifting up a tall building, much less a multitude of towers, could have come true without the unique bedrock that lies invisibly below the asphalt covered streets of New York City. in 2016, Mia Hull wrote of “Rock Scrambling and Bedrock: A Geohistory of Manhattan,’ in which she described the subterranean deposits that support a skyline: “Without Manhattan’s stable bedrock, the looming skyscrapers that are often conceived of as an integral part of its identity would not be supported enough to exist. It is interesting to consider how the formation of this particular part of North America, molded by the same processes as the whole globe, created such a unique city that is known for so many other things besides its geologic makeup and history..The primary three strata, or layers of rock..that form Manhattan are the Manhattan Schist, the Inwood Marble, and the Fordham Gneiss..” Writing for the website Next City, Stephen J. Smith noted that “The building is far denser than anything that would be allowed today — the developers multiplied their acreage by 30, twice the density that would be allowed on that plot today and three times what is allowed to its immediate south and east — and sits alone on its part of the skyline.” Living in earthquake country, whether California or Japan, one can appreciate how precarious a skyscraper can be in the wrong kind of terrain and marvel at the sheer weight that the foundation of Manhattan Island bears. The march of skyscrapers up and down the tiny parcel of land purchased from the Native Americans for around $20 continued during the twenties. And the newcomers, the Crystler Building and the Empire State Building, proved that no matter how tall the structure, the island could support it.

Architectural Drawings of the Buildings:

Architectural Drawings of the Buildings:

Chrysler on Left, Empire State on Right

On the surface, that is at street level, the Empire State Building was erected on the site of two hotels, the Waldorf (1893) and the Astoria (1897). The stretch of Fifth Avenue had been the site of many homes of many millionaires, but commercial properties were marching closer and closer. It was time for the rich to move their mansions elsewhere and start to take advantage of their real estate holdings. In an eerie prelude to the Raskob-Chrysler rivalry, two wealthy cousins who owned an entire block of valuable property between them had no qualms about leveling homes for two rival hotels. William Waldorf, cousin to John Jacob Astor IV, asked the architect Henry Hardenbergh to design a thirteen story hotel. Hardenbergh would go on to design the famous Dakota apartment building which is still standing. Astor answered Waldorf’s move with a hotel of his own, built a mere three hundred feet away. Eventually, the two hotels, the Waldorf and the Astoria, were connected by a tunnel called “Peacock Alley,” so named because of the passage on beautifully dressed guests from one hotel to the other. These hotels, remarkably modern for their time, were renamed the Waldorf=Astoria (note the use of the equal sign) and became the home of Nicolas Tesla, one of the great scientific minds of his time. The Gilded Age, celebrated in Peacock Alley and in the luxurious restaurants of the hotel(s) began to fade, withering under the glare of public anger over the excesses of the wealthy. After the Great War, the hotels themselves began to fall from favor as the fickle customers began to drift elsewhere. Indeed, like a warning bell in the night, in 1912, the luxurious ship the Titanic crashed into an iceberg and went down in about two hours. Some of the richest people in the nation also sank beneath the waves, including Astor. According to an account of his genealogy: “John Jacob Astor IV’s body was recovered by the steamer Mackay-Bennett on April 22 not far from the sinking. Reports say his body was covered in soot and blood, thus it is assumed he was killed by the first funnel when it collapsed as the Titanic made its final plunge. He was identified by the initials sewn on the lapel of his jacket. Among the items found on him was $2,500 in cash and a gold pocket watch, which his son, Vincent, claimed and wore the rest of his life.” According to Untapped Cities, Waldorf died in 1919, effectively ending an era of unbridled wealth and power. The twin hotels were sold and demolished in 1929 to developers who would launch into a building that would be one hundred two stories tall, dwarfing the family mansions and the hotels that became ghosts on the block. However, the pair lived on: a developer purchased the name Warldorf-Astoria (a dash this time) and proceeded to build a new hotel on Park Avenue. At the time of its rebuilding in 1931, this new iteration at forty-seven stories, over two thousand rooms spanning an entire block, was the largest hotel in the world.

The original Waldorf=Astoria Hotel/s on left

A new chapter in New York architecture was opening. Elegant private homes were being replaced by office buildings to house the growing army of workers flocking to New York to work in the businesses during the boom times of the Jazz Age. This time there was no warning as to the sudden change that would come, but like the Titanic hitting an iceberg, the market hit its limits and crashed. As it went down, two buildings went up: The Empire State Building and the Crystler Building, racing each other for the prize of being the tallest in the world. The next post will discuss the construction race and then the subsequent post will discuss the Art Deco design of the interiors.