Rephotographic Survey Project

Following Footsteps of the First Photographers, Part Two

One of the re-photographers doing “repeat photography” of the western territories, Rick DIngus (1951-), said “For the Rephotographic Survey Project, I was most interested in using repeat photography to investigate not just how the camera could help us record the world changing through time, but to examine how both the photographer and the medium of photography distort the world by rendering it as an image.” The process of transforming “land” into “landscape” or “space” to “place” is also the installation of a representation to take the place of the reality that lies on the other of the lens. As the photographer picks up a camera, places it on the steadying tripod and then points it into space, s/he marks and frames into a square or rectangle a judiciously selected segment that, upon printing, is transposed into what Dingus termed “an image.” For the original photographers whose task it was to document the post-Civil War Western territories creating images for consumption involved engaging audiences that would never trek through these alien and difficult terrains. The challenge was two-fold: to record and to make manifest. As was pointed out earlier, these Western spaces were trackless and as strange as the dark side of the moon itself, not just to those who would remain in New York or New Jersey but to the explorers themselves.

Timothy O’Sullivan (1840-1882), formerly one of Matthew Brady’s “operatives” and was just fresh from the battlefield of Northern Virginia, familiar and blood-stained terrain. Even while he was photographing the carnage during the Civil War, the photographers had models to base their conceptual apparatus upon–paintings of glorious battles with the dead expiring nobly. These precursors that were carried in the collective consciousness of the general public were what made the stark and unheroic pictures of ordinary men lying dead in the field so moving and tragic. O’Sullivan presented a stark reality of the costs of modern war to those who entered the studio of Matthew Brady and perused through the latest images from the front. One could imagine that the contrast between that which was expected and that which was actually delivered might have stayed in the mind of O’Sullivan as he stood in the glare of the strong sun looking over endless deserts with surreal (a word not in his vocabulary) outcroppings and tall mountains so harsh compared to the soft verdant curves of the ridges in the East. How could he present this unexpected strangeness? How could he produce an image?

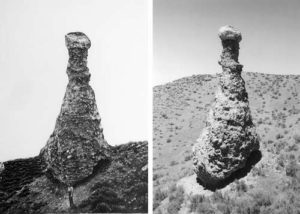

Unlike William Henry Jackson or even earlier, Carleton Watkins in Yosemite, O’Sullivan tended to present, not simply whole sweeping vistas and overall views, as seen in the paintings of Albert Bierstadt, but also intriguing fragments and small slices that are severed from the context and offered up as details. When he pulled back for a long shot, the result was a formal composition that was so unfamiliar or strange that many of his images were difficult to comprehend or put into a context. But his closely examined pieces of some larger whole are allowed to become compelling shapes in their own right, framed and presented like sculptural works. Nowhere was the oddity of the photographs of this photographer more starkly shown than in a famous pairing by Rick Dingus who, walking along the trail he led, re-photographed a strange growth protruding from the granular sand called Witches Rocks in Utah. In their article “Photographs as Evidence,” Ronald E. Doel and Pamela M. Henson pointed to the 1869 image as an example of an “altered landscape.” In comparison to some of their previous examples, such as the staging and rehearsal of Arthur Rothstein’s Dust Storm, Cimarron County, 1936, the alteration of the Witches Rocks was fairly simple. However, the transformation of what was into an “image,” as Rick Dingus expressed it was not known until the twentieth-century photographer revisited the site. As Doel and Henson wrote, “Photographic historian, Rick Dingus, seeking to recapture O’Sullivan’s Witches Rock, made an important discovery: in composing his photograph, O’Sullivan had tilted his camera about fifteen degrees from the horizontal thereby exaggerating the steepness and instability of the formation.” Rather than being a straightforward document, the image, which had been viewed as “an example of conglomerate rock from the Teritary era,” the authors stated, had been circulated a form of scientific evidence. As for the tilted camera..one can only speculate as to why–the desire for a formally pleasing composition? or was he experimenting with holding the camera in his hands? but tilted it was, shifting the photograph from the “document” category tot the advocate territory, perhaps as an argument for a popular theory of the time, the idea that geological formations were the result of a series of “catastrophes.” This theory put forward by Rick Dingus seems as good as any other explanation, but the first photographer was an employee who had no role as a scientist and did not, therefore, leave behind more than scattered on the matter.

The re-seeing of the original image by the re-photographer, Dingus, stressed the fact that O’Sullivan consciously constructed an “image.” In other words, what had been previously understood as a form of unmediated evidence was actually a synecdoche for a now-obscure theory of evolution. Today, thanks to the re-photographic survey, the photographers of the West began to be studied analytically, both within the tradition of the history of photography and from the vantage point of the environment and the technology or the how of photography. How the land was organized by these early photographers depended to a great extent upon their equipment and the results, that is, each precious surviving picture reveals the first interpretation, determined by wet plates placed inside large view cameras. The photographs of O’Sullivan would be re-seen and thus re-interpreted first as survey documents and as scientific texts and in the mid-twentieth century as works of art. For many decades, the work of this photographer was “lost,” meaning that they were no longer “useful.” The West was “won” and settled and familiar. Therefore, when O’Sullivan’s body of work was “found” or rediscovered, it was in a different era and within a new context. Just before the Second World War, the Museum of Modern Art established a department of photography in 1940. This action followed a landmark exhibition on the occasion of the centenary of the “discovery” of photography, “Photography: 1839–1937,” which was curated by Beaumont Newhall (1908-1993) and opened in March 1937. For such an exhibition to appear in America’s foremost modern art museum was to sanctify photography as “art,” and it would be Newhall who would become the head of the new department. With colleagues such as Alfred Stieglitz in New York and Ansel Adams from the West coast, Newhall had allies in his role in the museum: to solidify photography’s status as “art.” It was Newhall’s goal, an extension of the life work of Stieglitz—to argue that a photograph was a work of art, that would provide the context within which Timothy O’Sullivan’s photographs would be re-viewed.

Newhall had some knowledge of O’Sullivan as a war photographer but not of his work as a survey photographer who returned to the West many times. In his article, “‘Surrealistic and disturbing’ Timothy O’Sullivan as Seen by Ansel Adams in the 1930s,” Britt Salvesen wrote that it was Ansel Adams who discovered the O’Sullivan of the West: “Newhall was unaware of O’Sullivan’ssubsequent Western Survey work until January 1937, when Adams brought to his attention an 1874 album he had acquired from mountain climber and Sierra Club Bulletin editor Francis Farquhar, Geographical Explorations and Surveys West of the 100th Meridian. Led by Lieutenant George M. Wheeler of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, this expedition included two photographers—O’Sullivan and William Bell—and covered large areas of present-day Nevada, California, Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico.” In describing the aesthetic of O’Sullivan, Adams wrote that it was “technically deficient, even by the standards of the time but nonetheless, surrealistic and disturbing,” but later he revised his early judgment stating that the images were “all the more startling when one remembers the difficulties of processing the plates.” At this time, from the1930s to the early 1940s, the most significant presentations of photography had been the German exhibitions, the wide-ranging Film und Foto and Es kommt der neue Fotograf! both of which embraced New Objectivity. But the oppression of Hitler and the rise of Surrealism intervened with that particular discourse, and the Museum of Modern Art was a suddenly a major voice for photography as art. Neither Newhall nor Adams had experienced the German sensibility and when the former’s very important book on photography, History of Photography, was published in 1949, photography was understood, as Salvesen pointed out, as “art.” Had the images of O’Sullivan in the West been discovered in a decade earlier, they would have been “read” within the discourse of New Objectivity. But these photographs landed within the environs of “art” and the photographs were seen as abstract, even as surreal, as works of beauty. Adams, who was a member of the f64 West Coast group of photographers, saw the world in terms of shapes and forms. In addition, Newhall also worked to place O’Sullivan into a particular interpretation of “straight photography” and unmanipulated pictures.

According to Salvesen, O’Sullivan’s photographs presented some difficulty to Adams who struggled to understand the sheer strangeness of the work that somehow slipped the bounds of expected “landscape photography.” The work of Rick Dingus went a long way in solving the problematics of the project taken on by O’Sullivan, but, to the mid-century viewer, the reading was “discontinuous.” Salvesen wrote, “Certainly some of O’Sullivan’s pictures present us with disjointed spaces, illogical proportions, bizarre juxtapositions, and other compositional peculiarities that confounded even Adams, who was familiar with the actual places depicted.” In order to situate O’Sullivan into their photographic taxonomy, Newhall and Adams reinterpreted the nineteenth-century photography as a kind of innocent abroad. “Newhall and Adams, in order to establish O’Sullivan as a founding father of American photography, could not dwell on the “disturbing” aspects of his pictures,” Salvesen said. “Instead, they looked for other kinds of evidence or affinity to support the contradictory assertion that he was both an innocent eye and a consummate artist, because this, in turn, supported their ideas about photography’s essence: its independence from painting, its truthfulness, its capacity to depart from ordinary perception and stimulate insight, and its Americanness.”

Robin E. Kelsey’s 2003 article, “Viewing the Archive: Timothy O’Sullivan’s Photographs for the Wheeler Survey, 1871-74,” stated that Beaumont Newhall “implicitly heralded the work of Timothy O’Sullivan as a harbinger of modernism.” The author pointed to Ancient Ruins in the Cañon de Chelle, which “features stark geometric relations, radical value contrasts, instances of insistent planarity and graphic reduction, and other qualities in keeping with a modernist sensibility..If the modernists have suppressed the governing circumstances of O’Sullivan’s practice, the contextualists have suppressed his puzzling pictorial choices.” Kelsey took a middle path, suggesting that “O’Sullivan devised a specialized pictorial rhetoric to persuade viewers that the survey was securing practical gains in knowledge and that his medium could take part in this effort. In particular, his photographs conveyed assurances that the survey was translating the West into legible graphic materials that could facilitate resource extraction, military control, and scientific understanding..At times, he struck a skeptical note, making pictures that called into question the capacity of photography to deliver epistemological gain.”

It would take yet another photographer, following in the footsteps of Ansel Adams, who decided that the photographs of Timothy O’Sullivan were art, to see the same pictures for the third time. Rick Dingus was able to take the third walk into the West and to reconstruct O’Sullivan’s photographs. In other words, he did not attempt to place the photographs in a particular chapter of the history of photography, nor was Dingus interested in interpreting the work as “objective” or “surreal” or “art,” etc. He merely wanted to know where and how O’Sullivan planted his camera and started with the site itself, not with the photograph. What Dingus did was to investigate the production of an “image.” In re-producing the photograph, rather than re-presenting the photograph, Dingus solved the mystery of the work of Timothy O’Sullivan. Writing for Afterimage in 2001, Stephen Longmire recalled that “..perhaps the greatest conceptual achievement of the RSP, with their seemingly affectless pairs of images, was to create stereo “photographs” in the fourth dimension, their exposure time a virtual century. The real interest of these pairs is typically the space in-between, where all the changes occurred, or failed to. Are the housing developments and highways that appear, and the mines that occasionally disappear, developments or depredations? From the point of view of a century, the distinction begins to dissolve. Sometimes the absence of change is most salient. On isolated mountainsides, the positions of individual rocks can be compared across what is, after all, only a blink in geologic time.”

The images of the Rephotographic Survey Project of 1977 and 1979 were, on one hand, standard art historical comparisons of images from one time period being set up next to a nearly identical image from another era. The art historical purpose of comparison can be stylistic or subject matter but the pairing of the original and the re-make indicated that even if one can stand in the same place, at the same time of day, with the same camera, it is impossible to re-take the same moment. As was pointed out in the previous post, the focus of the rephotographing the West, rather than the East or the Midwest was that the West was and is “mythic.” If the pictures of the Rephotographic Survey Project prove or suggest anything it is that the moment of that myth has passed.