JEAN-LÉON GÉRÔME: History Painter

Part Two

The Artist and Gender

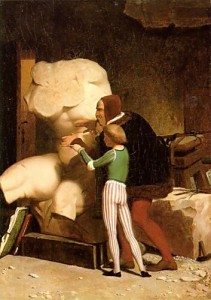

In painting after painting, Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904) clearly demonstrated his discomfort with women. Before his very profitable marriage to the daughter of Europe’s biggest art dealer, Gérôme lived a rather Bohemian life in a homosocial environment. Like most men of his time, he would have had little contact with women of his own class, and he would not have considered a woman to be his equal. His female nudes are far removed from actual women, and, as if their nakedness made him so uneasy, he had to use “the nude” as a mask for their disconcerting naturalness. But he is equally uncomfortable with male bodies. Both the gladiator in the celebrated Ave Caesar (1859) and the belly dancer in Dance of the Almeh (1863) are pudgy: the gladiator sports man boobs and the dancer has a large pot. But Gérôme was comfortable with little boys, carefully delineating their backsides in The Serpent Charmer (1880) and his early Michelangelo (in his Studio) (1849). In the former, the backside is bare, in the latter the backside is literally delineated due to a pair of red-striped tights, worn by the child. Many of his paintings are simply unseemly, in today’s terms, in their confirmation of the scopophilia of male desire for conquest through the passive gaze.

Prynne Before the Areopagus (1861) presents one of Gérôme’s repeated themes: men looking at an object of lust. The object, in this case a woman, is isolated and alone and, most of all, naked, totally exposed to the male gaze. The artist tried to have his specious content both ways—men gaze upon women but the beauty of women’s bodies subdue them, stun them into silence and submission. But the male is always clothed and always retains his power. Young “Prynne” is examined by a group of startled old men, dressed in strong red robes, countering her pale hairless body. Nowhere were women under the command of the male as she was in the mysterious East. The notion of the submissive and speechless woman could have been especially appealing to Frenchmen, alarmed by the propensity of Frenchwomen to rise up during each revolution at home. Thanks to the Code Napoléon (1804), French women had been stripped of any social powers and political disenfranchisement, stripped naked in custom and law.

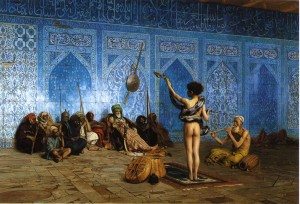

The Dance of the Almeh (1863) also empowers the men, who watch the gyrating dancer who writhes for their amusement. The males in the circle are equipped with long straight phallic instruments, guns, spears, violin bows and even a pipe, as though they are protecting themselves. The same excess of protection and phallic display can be seen in The Snake Charmer (1870). The old man at the center of the group has a long sword suggestively rising above his upper thigh as he watches the naked little boy playing with a long snake. The rest of the men are well equipped with erect spears, raising the unanswerable question of whether or not Gérôme was aware of the sexual subtext.

Gérôme. The Snake Charmer (1870)

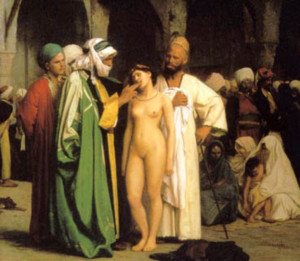

For Sale (The Slave Market) of 1866 is the ultimate expression of the stripped and speechless woman being exchanged among men (according to Engels). The slave market in the Middle East has replaced the European concept of marriage as a financial exchange and, as the catalogue essay on this painting reports that the French public “hardly batted an eye.” The idea that the “public” was unphased by this painting implies that the painting was intended for men, which it surely was, and that the art was not viewed by women, which it surely was. Although women of the Second Empire were apparently not expected to see art or to be the audience, but, when they went to the Salons, women were embarrassed by the painterly display of helpless female flesh. One can imagine that some of these ladies imagined the slave woman biting the fingers of the man who was examining her teeth.

Gérôme. For Sale (The Slave Market) (1866)

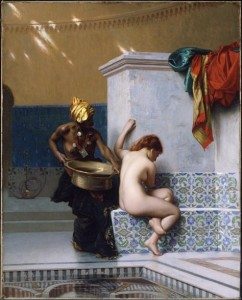

In other paintings, the (male) audience itself is outside the scene, looking it or looking at the imagined world of the harem. The external spectator was metaphorically internalized as a red robe reclining on a wooden chair in King Candaules (1859), watching the exchange of male looks. The King’s guard, Gyes, lurking in the dark, off to the right, is watching the queen Nyssia. The queen is caught in a triangulated gaze among men, but as Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) pointed out, she would not have been the “dull puppet,” depicted by Gérôme. As was typical for the artist, the woman is pale and naked and helpless with her back turned to the audience in a gesture of modesty thrown in by the painter. One could ask if showing a woman’s naked body from the rear is more or less discrete. The Moorish Bath (1872) is noteworthy for the carefully drawn Islamic tiles and for the inherent racism that exposed the naked breasts of the African slave and allowed the white woman to turn modestly away from the viewer.

Gérôme. The Moorish Bath (1872)

Echoing European and American notions of racial hierarchy, The Grand Bath at Bursa (1885) is yet another Imaginary Orient, complete with white women (presumably captured by swarthy Arab chieftains) who are sexual slaves and black women who take care of the needs of the concubines. At least in the harem, the women are together and have each other’s company. In many of Gérôme’s paintings, the women are alone, with no friend and no one to defend or take care of them, reflecting the Western version of marriage, the isolated woman, entirely dependent upon her husband.

The Artist as Colonialist

Much has been written about Gérôme as painter to the colonizers, and indeed his many trips to Egypt coincided with France’s desire to master the Middle East and to build an empire. Although their imperial ambitions dated back to Napoléon, the French never caught up with the British who had an empire upon which “the sun never sets.” The Second Empire and the Third Republic, the era of Gérôme, were the high points of French acquisition of territory and artifacts from northern Africa and the Middle East. Gérôme was at his best when he acted as ethnographer, observing the Other. As distasteful as the Imperial gaze was, it did have the virtue of freeing Gérôme from the tropes of classicism and the poncifs of academia. One does not often think of Gérôme the landscape artist, but, as my friend Irina pointed out, his desert paintings are beautiful, dappled with the blue of the sky reflected upon the pale golden buff-colored rocks, just as an Impressionist would (The Lion on Watch, 1890). Here in a desert light that flattens everything, the silhouetted sharp edges of Gérôme’s dry drawing make sense. In Arabs Crossing the Desert (1870), the large scale of the figures is permissible in such open distances. In these paintings of the Middle East, colors are intensified in the light and Gérôme came into his own with his strong colors, unexpectedly pinks (The Black Bard, 1888) and brilliant oranges and blazing yellows (The Marabou, 1888), hot reds vibrating on the surfaces (The Standard Bearer, 1876). The Color Grinder (1891) summarizes the importance of color with a row of large stone mortars lined up in front of a dark shop in the Holy Land. In an age of paint in tubes, Gérôme painted the encircled lips of the large stones, which are glowing with vibrant colors pounded into submission.

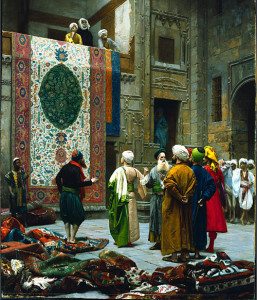

Although Gérôme replicated the Middle East and its male inhabitants with apparent exactitude, his paintings are fantasy pastiches. But they are totally convincing and carried a larger truth of white European fantasies of conquest and control of the inferior Other. The people he so carefully studied and observed during his many visits are from another century were devoid of technology beyond the seventeenth century, backwards and in need of French guidance. Heads of the Rebel Beys of the Mosque El Assaneyn (1866) mixed actual events with infidel barbarity, necessitating the civilizing French touch upon a people who favored a public beheading. The irony of such an attitude of superiority may have escaped Gérôme. (The French continued to use the guillotine into the 1940s.) A fascinating and harmless object of curiosity, entertaining the French audience, The Whirling Dervish (1889) needs to be Christianized and Europeanized. Due to the precise accuracy garnered from a photograph, the Salon goers assumed that the artist was educating them with The Carpet Merchant (1887). Each painting of Middle Eastern life can be seen as a contrast to European life–a market instead of a bank, souks, not department stores, fanaticism instead of Catholicism–with the Muslim barbarians being presented as the Other, as Different, as Inferior, as Strange, as Something to be Looked At, as Spectacle, captured by the artist, commanded by the whitened gaze of the spectator.

The Artist and Orientalism

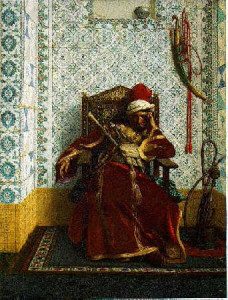

Gérôme seemed to suffer from a tendency toward a rather Victorian form of clutter and his penchant was to fill in his canvases with overwhelming detail about the Orient. Full of bric-à-brac, the paintings are crowded with information, much of which was gained from the artist’s many visits to the Middle East and documentary photographs recently published in albums. From one perspective, the artist’s work was typical of the a hoarder’s “horror vacui.” From another point of view, the artist was on a mission. The French tactic of conquest through military might and the gathering of facts dated back to Napoléon’s ill-fated foray into Egypt. The history of paintings of the Middle East done by French artists also stems from the early nineteenth-century when the Turks and the Muslims were depicted as brutal and backward. Gérôme nodded to his artistic precursor, Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), in his painting of Marcus Botsaris, a hero of the war of Greek Independence who fought with Lord Byron. But the 1874 painting itself, is typical of Gérôme’s approach to the unfamiliar: he delineated a veritable encyclopedia of an Eastern inventory of décor and paraphernalia.

Gérôme. Marcus Botsaris (1874)

Gérôme’s dedication to accuracy was part of larger tendencies: the rise of modern history writing, the rise of the French Empire, the use of photography to record and preserve the known world, and the period’s fear of empty space. Gérôme’s paintings are packed with these cultural vibrations of foregrounded empiricism. His art owed a great deal to the French delight in the Pre-Raphaelites and their facility for storytelling, which he put in the service of imperialism. It would be anachronistic to accuse the artist of “complicity” on a conscious level in an enterprise that would, a century later, be described by the French as “an accidental empire.” Undoubtedly, Gérôme shared the prejudices and desires of his time and believed in the right for the French to have an Empire and, whatever his motivations, his Middle Eastern subjects exuded Orientalism. His paintings were part of a deeply felt belief system of Western superiority and Eastern inferiority. In his investigation of the pioneering efforts of French artists in picturing the “Orient,” historian Todd Porterfield did not accept that the current French scholarship which insists that the imperialism of France was “haphazard” and “timidly entered into.” According to Porterfield, the French artists portrayed,

…national attributes are posited that pit French science, morality, masculinity, and intellectual rigor against supposedly representative traits of Easterners: fanaticism, cruelty, idleness, vice, irrationality, deviance, and degeneracy.

As was pointed out earlier, this was exactly the dialectical strategy employed decades later by Gérôme in his paintings of the Mysterious East and the Backward Other. It would be safe to assume that the artist believed, in common with most other Europeans, that the culture of the West or the Occident was superior. The discourse of racial and cultural superiority had been in the making among European scholars and writers for decades. The late Palestinian philosopher, Edward Said (1935-2003), revealed the role of discourse in the literary manufacture of “Orientalism” in his 1978 book of the same name. Although the cover of his book featured Gérôme’s The Serpent Charmer, Said did not discuss “Orientalizing” art. Said pointed out that when the Europeans wrote about the East, the scholars were creating, not the truth, but a “representation” of the “Orient.” Using Michel Foucault’s (1926-1984) concept of “discourse” in which serious speech acts from experts shape what becomes received knowledge surrounding a topic, Said stated in his book Orientalism (1978) that the “Orient” was constructed in terms of what the West was not. As Foucault pointed out, representation as constructed by the One would fabricate the Other into a inferior for purposes of discipline and punishment, power and control. Said continued the French philosopher’s thought by pointing out that an “Imaginary Orient” was manufactured for the purpose of defining the Europeans themselves by using the “Orient” as the negative to the Western positive. The Imaginary Orient had little to do with the “real” Middle East, for the Europeans were essentially uninterested in the Other and were concerned with the task of writing themselves into a position of dominance.

The concepts of Foucault and Said was quickly taken up by art historians, resulting in a major investigation into the attitude that European artists had towards the Other. Thanks to post-colonial theory, it is possible to view Gérôme and his art as an expression of French power over a dark-skinned people who refused modernity and Westernization. The art of Gérôme had to overwhelm the viewer with facts, information, detail, as though to compensate for a fundamental Lack of knowledge. Foucault equated seeing/sight with power–voir, savoir, pouvoir: to see is to know is to have power over. For all the privileging of vision in Gérôme’s work, the Other, the “Oriental” remained a slippery character in the French imperial drama. All the knowledge in the world is spread out on his canvases, but it is all from the French point of view and we learn everything and nothing. In the end, all the superiority, all the power in the world could not hold the Empire together, and today, as Porterfield, pointed out, the French seem vaguely embarrassed about their role in colonialism.

Looking at Gérôme’s art in today’s world is an interesting enterprise. The colonized subjects of the French empire have long since come home to the Mother Country, unsure of their identities, as Frantz Fanon (1925-1961) so eloquently stated in Black Skin, White Masks (1952). So thoroughly imbued with the doctrines of colonialism and imperialism, the colonized think that they are partly “French” and came to France to live, but they insist on bringing their “Oriental” culture with them. Suddenly, what seemed exotic in the Middle East caused controversy in Paris: head scarves or not? The fear of the Other continues. Gérôme, like all artists, was engaged in acts of representation; and, as for his attitudes, his biases, his complicity, his patriotism—that is for history to decide.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.