A Modern Workshop

Beyond Biedermeier, Part One

The Wiener Werkstätte was an idea about modern design. That said, as modern as the concept of the Workshops was, its historical roots can be traced back to the early nineteenh century Biedermeier period, when, weary of Napoléonic rule and wars, the Germanic populations of Germany and Austria turned inward, relinquished political life and embraced private life of home, hearth, and family. This emphasis on domesticity resulted in the creation of a style of furnishings in which the local carpenters picked up their planes and shaved off the flourishes of the aristocratic past, producing a more simple, more modest bourgeois approach to the home. The Biedermeier style, moreover, was for everyone, the middle classes, and was historically rooted in this newly emergent class, wedged uncomfortably between the aristocrats of Vienna and the teeming undifferentiated lower classes. According to Helga Kessler of the Metropolitan Museum of Art,

The term “Biedermeier” originated with a series of poetic parodies published in the satirical magazine, Fliegende Blätter between 1855 and 1857 by two German writers..(who) made use of the fictitious character “Herr Biedermaier” to poke fun at a class of staunch conservatives whose ideal it was to live unobtrusively, self-contentedly, and comfortably without its own four ways. (“Bieder” in German means upright, staunch, loyal, trustworthy; “Maier” or “Meier” is a common surname). It was only toward the end of the nineteenth century that this term was used by historians to describe the earlier years of the century and “Biedermeier” soon became synonymous with “the good old days.” This name is now applied to the years from 1815 to 1848–from the end of the Napoleonic Wars to the revolution of 1848. “Biedermeier” has come to stand for a life-style that expressed itself in the arts, philosophy, and fashions. The Viennese Biedermeier developed its own particular flavor and can perhaps be considered the most typical version of the Biedermeier style, although Biedermeier also pervaded western Europe as well as America.

Leopold Zielcke Zimmerbild (chamber painting) of a Biedermeier interior in Berlin (1825)

For Austria, and Vienna in particular, the Biedermeier style was all encompassing, including fashion for women as well as home furnishings, even extending to philosophy. After almost fifty years of dominance in the Empire, time was up for the Biedermeier style. Architects and artists were reexamining the ethos of Biedermeier both in life style and in clothing. According to the book, Alois Riegl in Vienna 1875?905: An Institutional Biography by Diana Reynolds Cordileone, “Biedermeier was the pejorative that had been applied to modest interior decoration..It was, as Riegl had noted, a local expression of Empire style, but downsized from aristocratic use for the city apartment; thus suitable for the middle class consumer..this design idiom was now transformed into a new candidate for an Austrian design identity. The Biedermeier decorative style, with its reduced ornamentation and simple outlines was also easily transformed into contemporary manufactured items. After 1896 curators at the museum, along with the other critics, began to promote the Biedermeier as the true Austrian design style.” Cordileone also pointed out that the style “focused on the private world of inherited responsibilities and duty to one’s position..” where men in particular found refuge from ” the crassness of public and commercial life.” By the end of the century, the Empire was increasingly challenged by the numerous ethnic and religious conflicts uneasily contained in the strained boundaries and the idea of the middle class retreat provided a welcome respite from “the increasingly painful nationalist and social questions in the monarchy, and its light, bright interiors symbolized reason, cleanliness and modernity.” The characteristics of the Biedermeier style was characterized by “polished woods, light color schemes and fabrics, cleanliness, and fine craftsmanship. Eventually the Biedermeier mantra was taken up by the Secessionists, and it became part of a set of ideas that linked Austrian identity to modernity.” However, as the author pointed out, the Biedermeier was “just another form of historicism..”

Biedermeier or simplified Empire style

Not only was the Biedermeier historicist it was also a retreat from reality and the style began to signify a refusal to move forward and to meet the new century with a singular and identifiable voice. In his book, German Home Towns: Community, State, and General Estate, 1648–1871, Mack Walker noted that the Biedermeier was “a style of withdrawal, and what it withdrew from was the massing of forces and the pervasiveness of change that marked public consciousness of the nineteenth century from its very beginning. Biedermeier culture was a tense and precarious culture because its essence was the containment of opposites: the quiet style itself in the foreground, and the Biedermeier sense of radical change, in the middle distance but inseparable from the foreground’s insistent quiet..The Biedermeier was a hometown style, even when it took hold in the mansions of the rich and the palaces of the mighty..the Biedermeier was..bürgerlich. It was a hometown style because at the baseline of withdrawal stood the home town as an obvious symbol of permanence and stability. The hometown principle of enclosed familiarity, adopted into the general culture to contain and explain sharp division and instability within the general society, was the Biedermeier principle.” By the new century, the creative intelligentsia, sensing the internal crisis of the Empire, began to seek a style that was transcendent of time and place, politics and ethnicity. However, stripped down and vaguely classical, the Biedermeier style was too immeshed in the past to suit the needs of the twentieth century. A vague idea of “modernism” or a style that was “modern” began to emerge, and it was Vienna where much of this dialogue was written.

Wiener Werkstätte, Neustiftgasse 32-34, Vienna

Modernism in Vienna was posited against a dominant and exhausted style, the Biedermeier, which was favored by all who could afford the furnishings and the clothing. In a sense, the Biedermeier was a class-less style, but it was a regressive style, always looking away. The Wiener Werkstätte positioned itself in a progressive site, steering away from the taint of mass manufacture that steeped into the Biedermeier, due to its ubiquitousness. Where the Biedermeier was everywhere, available to everyone, the artists of the Werkstätte fashioned themselves as artists, craftspeople, artisans who produced unique products. While the Biedermeier appealed to the emperor and the prosperous grocer alike, the modern works of art that came out of the Workshops would be appreciated by the sophisticated and the art educated, and most significantly, the well to do. When it was founded in 1903, by by Koloman Moser and Josef Hoffmann, ideas of “modernism” and the concept of “modern design” were still vague and the artists needed willing partners in their experiments as they reached for “modernity” in design. The general public of Vienna were, as their fondness for the Biedermeier indicates, not adventurous, and the Wiener Werkstätte artists preferred to work for wealthy patrons with high end tastes and purses to match. As Carl Schorske pointed out in his introduction to Viennese Design and the Wiener Werkstätte (1986), the artists, architects and craftspersons of Vienna were forced to consider the private client. The major building campaign of the mid-nineteenth century, the Ringßtrasse had ended and those major public commissions had also come to an end.

Although at its height, the Wiener Werkstätte employed over a hundred craftspersons, it was never a firm in the sense of being a business. More specifically, the goal of the Workshops were never to become commercial or popular and the designs were always conceived within the very specific world of the decorative arts. The artists were part of the avant-garde of Vienna during and after the fin-de-siècle period. Because of its situation, that is where the Werkstätte was situated, the artists had a very specific patronage that included collectors and patrons who supported the avant-garde in general and their designs could be experimental and forward looking without have to be concerned about public tastes. In the case of the Workshops, their patron was Fritz Waerndorfer (1868–1939), the sion of an Austrian textile family that owned a spinning mill, the Waerndorfer-Benedict-Mautner, part of the largest textile company in the nation. Like other patrons of the avant-garde, Waerndofer was from a prosperous Jewish family and well before the Werkstätte was established in 1903, he was a collector of the paintings of Gustav Klimt, sculpture of George Minne, and the drawings of Aubrey Beardsley. His cutting edge art collection was displayed in gallery designed by Koloman Moser. One of the most important collectors of the designs of Charles Henry Mackintosh, Waerndorfer was a logical choice to support the Wiener Werkstätte.

Friedrich Fritz Waerndorfer (1868-1939)

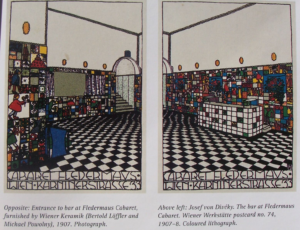

The audience and the buyers of the products of the Wiener Werkstätte were the intelligentsia with elite educated palettes. But the preciousness of the work should not oversee that fact that the Workshops were part of a complex network of production on one end and distribution on the other that was so high quality and so effective that the impact of the Werkstätte reached into Paris. The fact that the organization was founded by two architects, Dagobert Peche (1887-1923) and Josef Hoffmann (1870-1956) and a designer and painter Koloman Moser (1868-1918) pointed to the collaborative nature of the enterprise, which brought together people from the fine arts such as Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) to combine the artistic forces that brought an international reputation to Vienna and its inventiveness. It is no accident, therefore that the Workshops were a part of the Vienna Secession, a movement that separated the traditional art world, based on an outmoded classicism, in order to pursue modernity. The Secession and the Werkstätte shared artists and designers and had a common point of view, to change the aesthetic of the coming century. However, the intersection among artists, architects and designers which stressed interactive collaboration also led to the creation of the Gesamtkunstwerk, an idea out of the older Arts and Crafts movement. Because the clientele was so rarified, the quality of the work and the materials used could be very high, again rather like Art Nouveau was dedicated to unique hand made objects. But the Werkstätte was also perfectly capable of sending out hundreds of postcards to advertise their wares. The Workshops also had a social headquarters for those who wanted together and discuss their ideas about art: the Kabaret Fledermaus, founded by the patron, Fritz Waerndorfer, and designed by the members of the group.

Similar to the Arts and Crafts movement, the Werkstätte wanted to reform design and to modernize the aesthetics of interior design. Like the Aesthetic movement, the Workshops kept to a particular mode of modern design, spare and restrained, with many manifestations and variation on the geometric theme. By creating and maintaining a particular style, the artists could work together effortlessly in a collaborative project with the result being a Gesamtkunstwerk—a total immersion in the modern style. And yet, despite the lofty aims, the products were intended, according to the Manifesto to be “available to everyone.” The Viennese Secession first drew favorable attention to its artists at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900, revealing that Paris or Berlin were not the only sites of modernity in art and design. The next two posts continue to discuss the Werkstätte.