The Modern Workshop

Like the Viennese Secession, the Wiener Werkstätte emerged as an independent body of artisans out of the prevailing concern among a young generation of artists about the stagnation of culture in Vienna. The Akademie de bildende Kunste, with classical inclinations and historicism on the mind, was the main purveyor of education and new artists. The Kunstlerhaus Genessenschaft, the leading organization for exhibiting art had its own Ringstrasse building of Italian Renaissance design, which reflected the conservative viewpoint of those who determined which works of new art could be displayed. As was typical in Vienna, the dismayed and disaffected artists would gather in coffee houses to discuss their own ideas about art. Those who would become the leaders of the Werkstätte formed the Club of Seven at the Café Sperl and a mid-career muralist for the Viennese government, Gustav Klimt, began to reconsider his role as an artist during these sessions with the Siebener Club. The artists who would become part of the Wiener Werkstätte, which was founded in 1903, cut their artistic teeth in the Secession, founded in 1897, giving Josef Hoffmann (1870-1956) and Kolomon Moser (1868-1918), an exhibition site to show their talents as graphic designers among “fine artists.” The Secession not only allowed but encouraged this erasure of the line between fine and applied arts, a pioneering move that would be followed by the French salons after the Great War. When the Werkstätte was founded six years later, it was part of a wave of experiments in which artists attempted to find and develop a new vocabulary that would lead the way out of historicism and into the twentieth century and the modern era.

The ultimate goal shared by all the artists was to create modern look for contemporary design, but the Great War split the design movement in half. Before the War, design shared characteristics of Art Nouveau but looked forward towards a more spare and geometric modernity. After the War, the traces of Art Nouveau were relegated to the past and the precision of a machine aesthetic came to the fore. However, the transition from the curvilinear to the linear was a bit more complicated in Vienna than a mere shift in taste or culture. As Elana Shapira wrote in her article, “Jewish Identity, Mass Consumption, and Modern Design,” Jewish patrons were leading figures in supporting modern design. In addition to Fritz Waerndofer (1868-1939) in Vienna, there was Siegfried Bing (1838-1905) in Paris, and Emil Rathenau (1838-1915), owner of AEG, the huge electrical company, in Berlin. The famous designer Peter Behrens was the house designer for the forward thinking Rathenau who needed new design ideas of his new technology and modern products. Shapira suggests that these patrons were interested in substituting or layering what she termed a modernist corporate identity over the “Jewish character.” For them, the integration of the Jews into the larger and hostile society would be through the vehicle of good design and elevated taste. The patronage of high end designers producing designs and products for very elevated consumers was meant to counter the anti-Semitic sentiments surrounding “Jewish capitalism” as witnessed in department stores. Wiener Werkstätte output would be exhibited in international art exhibitions and not on the counters of Galeries Layfayette in Paris. The author described the patronage of avant-garde design to a counter-movement in which “the three entrepreneurs chose to create a modern “corporate identity” with unified looks for their enterprises that represented a distinct aesthetic character.” Unfortunately, in an anti-Semitic period (that would continue for decades), merely being Jewish opened one to the charge of being Jewish; and for Siegfried Bing, the label “Jewish taste” was immediately attached to Art Nouveau because he owned a store of that name. For the Jewish patrons, the arts were a path to assimilation but, in order to be “accepted” by the Gentile society by, in the case of Bing, contributing to French culture, or in the case of Waerndofer, contributing to Viennese distinctiveness. Although the reception of Bing’s establishment, three years before the establishment of the Wiener Werkstätte, certain critics, such as Karl Kraus, colleague of Adolf Loos, connected Art Nouveau to “Jewish taste.”

Willow chair was designed by Charles R. Mackintosh for the “Willow Tea Room” in the 1903 in Glasgow

In his book, Art in Vienna, 1898-1918, Peter Vergo reported of the Secessionists, “Their aim was to introduce to Vienna the work of some of the foremost designers in Europe. Room X of the exhibition, the layout of which was designed by Mackintosh and his wife, was set aside for their collection. This show marked the beginnings of cordial relations between the Secession and the British artists who had been invited to Vienna especially for the occasion.” In the article, “How Charles Rennie Mackintosh changed the Vienna Secession,” Phadion wrote of “a letter dated 17 December 1900, Mackintosh thanked the committee for their kindness, stating ‘I know well the artistic achievement of your exhibition. I hope it is receiving that public recognition and support which it deserves.‘” Indeed, Mackintosh and his rectilinear approach to Art Nouveau was important to the twentieth century work of the Wiener Werkstätte designers, who, like the Secession artists, had separated from the high culture of Vienna. And the designers also eschewed the endless repetition of old styles that were being cranked out—literally–through mass production. As Heather Hess expressed it, “The Wiener Werkstätte’s founders rejected the legacy of historicism and tackled the problems of industrialization. Their goal was to tap the lost traditions of preindustrial craftsmanship to raise the level of Austrian design.”

As Hess wrote in her article “The Wiener Werkstätte and the Reform Impulse,” the founders of the Wiener Werkstätte, Josef Hoffmann (1870-1956, who was a student of Otto Wagner, and Koloman Moser, were also professors at the Kunsgewerbeschule or the Imperial-Royal School of Arts and Crafts where they educated the next generation of designers. Because of the willingness of the Secession to give design a prominent place in the contemporary culture of Vienna, the artists of the Wiener Werkstätte were an integral part of the movement dedicated to creating a modern art for the new century. Hoffmann participated in the 1902 Beethoven exhibition and was the director of the collaborative works by twenty one artists. The XIVth Exhibition of the Association of Visual Artists Vienna Secession is famous for Gustav Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze. The concept of this exhibition was to produce a synthesis among architecture, painting, sculpture, music and decoration. All the arts were united as one in the exhibition which became one of the Secession’s most successful, attracting 60,000 visitors. Just as the designers worked to support the Secession artists, the Secession artists in turn, such as Gustav Klimt and Oskar Kokoschka contributed designs to the Werkstätte. Regardless of rank each artist who worked on a product was called out through the inclusion of a makers mark on the object.

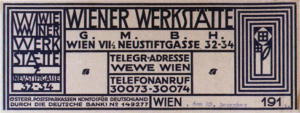

According to Elana Shapira, the charges of failure to articulate a style that was distinguishable from Art Nouveau, made by Adolf Loos, led Joseph Hoffmann to alter his style from curvilinear to geometric, in an effort to move away from Art Nouveau (Siegfried Bing) and shift to a style that had no pre-existing identification. Another impetus, which manifested itself clearly in the Werkstätte was the impact of the straight lines of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, who showed the way out of the Jungenstil cul-de-sac. Mackintosh, like his Austrian colleagues, was multitalented; someone who produced exquisite drawings, striking and original furniture and who raised humble cutlery to a collection of art forms rather than mere knives, forks and spoons. His very formal and very geometric designs were curiously thin and flat, as though cut out from paper which served as a pattern for a wooden version. Furnishings by Mackintosh did not accommodate themselves to the curves of the human body but his appearance in the Eighth Secession Exhibition in 1900 impressed Josef Hoffmann so much that two years later he traveled to Glasgow to meet with the artist in person. It could be argued that Mackintosh showed the future artists of the Werkstätte a road map out of Art Nouveau, countering its exuberant curves and twists with strict geometry. Kolomon Moser, who like Hoffmann, was a graduate of a technical university and, like Hoffmann, was on the faculty as a graphic artist, used the inspiration provided by Mackintosh to create a modern typography. Moser placed his sans-serif letters in a confining square that imposed a straightness upon his lettering. The new typeface was fully integrated into the design space designated by the artist, who predated the Bauhaus by some twenty years in devising an alphabet for the new century.

Wiener Werkstätte letterhead with flower motif by Koloman Moser

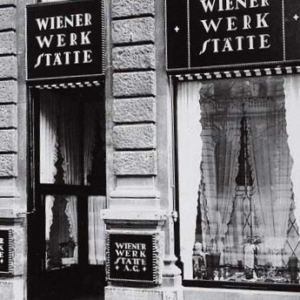

By the time the Wiener Werkstätte was founded in 1903, their squared spare style was already in place. In a shift from exhibiting in the Secession, the artists formed a business, based on the benevolence of a variety of benefactors, starting with Waerndofer. However, as the new volume, Wiener Werkstätte 1903-1932: The Luxury of Beauty (2017) pointed out, the Werkstätte began and ended in financial difficulties. The monetary issues that dogged the Werkstätte were the same that doomed the Art Nouveau movement. Handcrafted works of art were expensive and only a few sophisticated clients could afford to purchase them. But the problem was deeper than that. As the article in the most recent book on the Werkstätte, “Economics” by Ernst Ploil noted, it was difficult to estimate the cost of designing and manufacturing unique one of a kind prototypes and/or objects crafted for patrons. From the start the artists worked with inherently luxurious materials, beginning with silver, meaning that the business operated constantly at a loss, torn between producing high quality objects of art and the costs of production itself. Thus the Werkstätte was constantly dependent upon the kindness of others, who as benefactors, more or less mismanaged the business end of the company. Waerndofer, for example was a donor not a financial manager. HIs place was taken or supplemented by Hoffmann’s patron, the very generous Adolphe Stoclet, but even the famous multi-artist project, the Palais Stoclet, would not keep the company afloat. In desperation, Waerndofer appealed to Editha Mautner-Markhof, the very wealthy wife of Kolomon Moser. Mautner-Markhof was unwilling to shoulder the financial burden and, upon finding out that his wife had been put under pressure to donate to the cause, Moser separated from the Werkstätte. He left behind a design legacy but his departure was a great loss for the Werkstãtte. After the Great War the firm was taken over by the Primavesti family, Otto and Eugenia, who in turn brought in Kono Grohmann to bring the affairs to order. The monetary position of the Werkstätte was untenable. Although it had many divisions and many parts, although it was an international business, the original problems were never solved, suggesting that the dream of William Morris and the English Reform Movement in design were impossible to fulfill. Building a work of art, manufacturing a work of art, selling a work of art–three very different functions, separated from the artistic vision itself, was not sustainable in a modern era without royal patronage.

The “total work of art” of Weiner Werkstätte

And yet Wiener Werkstätte left its design mark. Its ideals were those of another era and it can be said that the artists and designers were caught in between eras–the era of hand crafting and the era of mass manufacturing–and could not square the circle. the In 1905, Josef Hoffmann wrote the Manifesto for the Wiener Werkstätte, stating, “So long as our cities, our houses, our rooms, our furniture, our effects, our clothes, and our jewelry, so long as our language and feelings fail to reflect the spirit of our times in a plain, simple, and beautiful way, we shall be infinitely behind our ancestors.” Hoffmann (and Moser) continued along the lines of William Morris before them: “The immeasurable harm caused in the realm of arts and crafts by shoddy mass production on the one hand and mindless imitation of old styles on the other, has swept through the entire world like a huge flood. We have lost touch with the culture of our forebears and we are tossed by a thousand contradictory whims and demands. In most cases the machine has replaced the hand and the businessman has taken the craftsman’s place. It would be madness to swim against this current. Usefulness is our first requirement and our strength has to lie in good proportions and materials well handled. We will seek to decorate but without any compulsion to do so and certainly not at any cost The work of the art craftsman is to be measured by the same yardstick as that of a painter and the sculptor.”

Ironically, the geometric motifs of the Wiener Werkstätte would pave the way for the post-war design movements to come, most particularly the Bauhaus and the architecture of one of its severest critics, Adolf Loos.