THE REMARKABLE WEDGWOODS

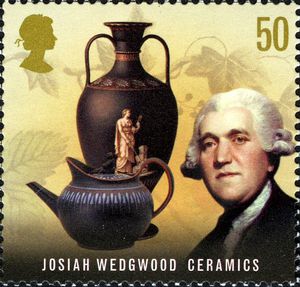

Josiah Wedgwood (1730-1795) and Thomas Wedgwood (1771-1805)

Photography and Pottery

Josiah Wedgwood was potter with a problem. Success. He had invented a new formula for making a durable and beautiful earthenware to take the place of expensive and fragile Asian and German and porcelains and Dutch faience. With an eye to mass production, the clever Wedgwood succeeded in creating a stoneware using clays from Staffordshire, Devon and Cornwall. As Bryon A. Born’s 1964 article “Josiah Wedgwood’s Queenware” explained,

The advantages of the new ware were numerous. Since the chemical properties of body and glaze were similar, the finished product was less liable to crazing or chipping. It was almost as impervious as glass to food or strong chemicals, and held no risk of lead poisoning. Furthermore, the clay used was of a finer texture than previous earthenware compositions and had much greater plasticity, permitting it to be molded into thin, light pieces of almost any shape. This last was a commercial as well as an aesthetic advantage..But with his lighter, stronger product he could ship more for the same bulk or weight, and reduce the danger of breakage as well.

In order to raise his profile, Wedgwood presented to Queen Charlotte a lovely near white set–called “creamware”–for her personal breakfast, with edges of the cups and saucers and pitchers banded with enlivened leaves of green against a gold background. The queen was pleased enough to order place settings for dinner. Although a modern version of this gift survives, all of the original pieces were destroyed over time but, for his pains, Wedgwood was given the tile, “Potter to the Queen.” Now he could market his pottery as “Queen’s Ware,” but his use of this unique mixture of clay ranged from the expected dinner ware to useful objects produced from molds which were sold all over Europe and even reached the American colonies. In fact, it was Wedgwood who originated one of the early versions of the assembly line to accommodate this enormously successful venture into “Queen’s Ware.” But his ambitions extended to Russia and he angled for none other than the Empress Catherine herself and succeeded in gaining a commission to produce four sets of creamware. The set designed for Catherine survived to modern times and was decorated with purple flowers and wheat husks, and, therefore is known as the “Husk Set.” As Born reported,

No one knows just how many pieces com-prised the original Husk service. It can be deduced that the set was a large one, probably containing several hundred pieces. It was in use about seventy years and then dropped out of sight. In 1931 part of the set-about sixty miscellaneous plates -was discovered and bought from the Soviet government’s surplus antique store by the wife of a member of the Finnish Legation in Moscow.

But this was just the beginning. The Empress was so delighted with the service she order another for another palatial setting. This order was anything but modest. Born continued,

It was for use at her St. Petersburg palace La Grenouilliere- so called because of the thousands of frogs inhabiting the surrounding marshes and each piece was to bear a different view of Britain as well as the palace crest, a green frog. When Wedgwood acknowledged the order, involving well over 900 pieces, he had two reservations: the monumental task of securing enough views of English castles, abbeys, gardens, and other suitable landmarks to go round; and the inadequate price-500 pounds..

Of course, the actual cost of such an undertaking would be much higher and Wedgwood contacted Catherine directly to negotiate and, according to Born, the final cost was probably about 3000 pounds. The Empress was a difficult person to deal with and anyone who did business with Catherine was liable to end up with the distinction only of having sold her products not the distinction of having been paid by her. She gave Sèvres commission was executed but the French Revolution gave Catherine the excuse to not pay for the work. A huge Danish commission took so long that she died during the execution and her successor refused to honor the sale. The set was delivered in 1774 but part of the service seems to have disappeared during the nineteenth century. The rest was located stored away, improbably, in the chapel of the Winter Palace of St. Petersburg in 1909. Over 800 pieces, as Born noted, show views of a now vanished England on the earthenware. Therefore, for the history of photography, this Frog service is significant because of the Queen’s desire to have her set illustrated with views of England.

A piece for La Grenouillière

The “Russian Service” was such as large task that the workshops at Wedgwood and Bentley were stretched to their limits. According to William Burton’s Josiah Wedgwood and His Pottery (1922), the business spent three years alone gathering views of England form collections of prints and drawings, etchings, engravings, and popular prints. As Burton wrote,

Various London print-sellers were just then publishing illustrations of the town and country mansions, with their parks and gardens, belonging to the nobility and landed gentry of the British Isles..Drawing freely on all these fountains of supply Wedgwood and Bentley purchased water-color drawings and sketches form some well-known British painters such as George Barret, R.A., who prepared a number of London drawings..Views of Hampstead were taken from designs which had been engraved by J.B.C. Chatelaine for Boydell the print seller..In addition to availing themselves of all such sources of supply or those brought their notice by eager agents among booksellers and print-sellers, Wedgwood and Bentley employed a number of architectural and topographical draughtsmen..

Burton noted that Wedgwood also solicited permission from landowners to use drawings of their homes on the plates for the “Russian Service. He quoted Wedgwood as telling one landowner that the Empress had commissioned “more than 2000 pieces upon each of which is to be a real view from English gardens and pleasure grounds painted in Enamel. We are to note each piece & send a Catalogue to the Empress saying from whose seat each view is taken.” Such letters resulted in his project being “warmly received,” as Burton put it in the Midlands, even putting families in competition for the honor of being featured. When the set was completed in 1774, it was put on display in the firm’s London show rooms called Portland House and was described by one of the visitors as consisting of “as many pieces as there are days in the year, if not hours.” The entire service took up five entire rooms on two floors. Sadly Burton does not reveal whether or not Catherine, who was delighted with the set, ever paid for the Frog service.

Thomas Wedgwood, the son of the famous Josiah was three years old, when the service of the Empress of Russia was completed, but the enormity of the commission became part of the family’s history. But perhaps most importantly, the son inherited his father’s curiosity and ingenuity and love of tinkering and the desire to solve problems. Imagine how much easier it would have been to use precise images gathered together from one source–a camera–for consistency and ease of transposition from one surface to another. An image of a country house could be obtained with a camera obscura, no doubt, but the issue was how to keep or retain the picture. With neighbors such as the Darwins, Erasmus the physician and his grandson, Charles, and Joseph Priestly, a chemist and member of the Lunar Society, and the engineer James Watt, the engineer as family friends, it was logical for the young Wedgwood to study science when he went to Edinburgh University at age fifteen. Meanwhile his boyhood tutor, also a chemist, kept his young charge apprised of the experiment of Antoine Lavoisier (1743-1794), who would die under the guillotine in Revolutionary France.

According to Richard Buckley Litchfield in Tom Wedgwood, the First photographer: an Account of His Life, His Discovery and His Friendship with Samuel Taylor Coleridge Including the Letters of Coleridge to the Wedgwoods and an Examination of Accounts of Alleged Earlier Photographic Discoveries (1903), Wedgwood was at Edinburgh for three years and worked at his father’s business at Etruria for the next three years until 1791. It is during this brief period that he conducts a number of experiments, including those utilizing the silver cylinders and he published two papers on his work. But by 1792, ill health prevented him from proceeding as a scientist. In fact there is a letter to his father, written when he was twelve, in which young Thomas mentions that he has a headache. In April 1792 he wrote, “..finding my health impaired, I resolved to give up experimenting..” It is noteworthy that one of the surviving photographs he made–called “sun pictures”–is an image of an illustration, making one wonder how easy a photograph of an illustration would have been to be transferred to the surface of the pottery. But the technology was still too primitive.

In the next post the experiments of Wedgwood and his colleague Humphry Davy will be described.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.