PRESERVING THE PAST

Mission Héliographique: Origins

Part One

One of the major problems raised by the French Revolution was the status of the Catholic Church. With everything old swept away, including the monarchy, the nobility, and religion itself, the brave new world of the Revolution was totally secular. The Revolutionaries took their revenge upon their religious oppressors and began to dismantle the power of the Church along with the power of the monarchy. Like the Church in England before the Dissolution, the religious institutions of France, worked closely with the State, held about six precent of the land, collected agricultural tithes and was exempt from taxes. In the fall of 1789, the legal disentangling of Church and State began, and at the beginning of 1790, the new Revolutionary government took over the lands and possessions of the Church, closed its religious houses, removing the Catholic Church as the official state religion. In 1792, it was decreed that all traces of “feudalism” should be removed from public spaces. “Feudalism” indicated the Church and the privileges of nobility–all of which was to be erased and extinguished in the face of a new history beginning in the Year One.

But it was the secular years of 1793-94 that constituted the “dechristianization” of France in which religious symbols were outlawed and churches, cathedrals, and ecclesiastical libraries were destroyed. The program of deliberate destruction on the part of the outraged people was tactfully termed “deconstruction” by the Revolutionary government. The citizens of the new France attacked the Church of Saint-Denis. Located just out side of Paris, this edifice was the place where French monarchs were buried, and in a clear statement of the destruction of the ties between church and state, the mob broke into the crypt and into the tombs, strewing the bones of royalty in the grounds of the church, even making off with souvenir bones. Although the remaining bones were later gathered up and buried in a common grave under the direction of Napoléon, by the early 1790s, the sight of wanton destruction had already concerned wiser heads in Paris and all eyes turned to the Bishop of Blois, the Abbé Henri Grégoire (1750-1830), who was asked to produce a report on the desecration of church property.

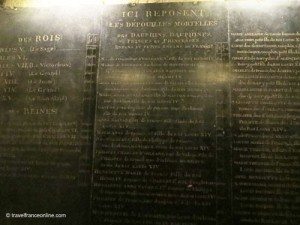

Ossuary of Saint-Denis where the bones of the kings and queens of France are collected.

A high-minded principle-driven religious leader and defender of the people, Henri Grégoire was instrumental in installing an unprecedented religious tolerance during the Revolution and is better known today as a staunch abolitionist. However, he should also be remembered as the man who came up with a new an unprecedented concept: that a nation and its people were responsible for the preservation and protection of its cultural artifacts–its own defining history. It is under his pen that a new word emerged in the wake of the dismantling of an entire history at the hands of mobs throughout France: “vandalism.” The term emerged during the Revolution, coined by Joseph Lakanal, who was a member of the Committee of Public Instruction and as such presented a report to the Committee on the national heritage which was systematically being destroyed. It was Abbé Grégoire who popularized this new word. In 1990, Joseph Sax wrote about this remarkable moment in time in the Michigan Law Review with his article, “Heritage Preservation as a Public Duty. The Abbé Grégorie and the Origins of an Idea.” Sax began by asking a question of his own, “How did protection of cultural values come to be viewed as a proper public concern in a modern world centered on the liberty and autonomy of the individual?”

It took a long time for the idea of heritage to be formulated as a public concern and to become the subject of public discourse. And when it happened, it did so in the most unlikely setting. The place was revolutionary France and the year 1794. Out of a reign of destruction came a plea, a theory, and a plan for protection of cultural artifacts, the genesis of modern preservationist thought..Beginning in August of 1794, Grégoire produced the three reports to the National Convention for which he is best known. The first is entitled Report on the Destruction Brought About by Vandalism, and on the Means to Quell It. Each report was originally requested only as an account of the losses the nation was sustaining. But Grégoire used the opportunity to consider a question that had never before been the subject of legislative attention: Why should caring for paintings, books, and buildings be a concern of the nation? Why, especially in a republic that was beginning radically anew, should monuments redolent of the values of the old regime be respected? Grégoire’s reports, which have never been translated into English, stand as the first expression of what has become a modern public policy on cultural property.

Prior to Abbé Grégoire, there was no clear policy towards historic buildings which could fall into neglect and ruin and could be torn down and replaced and updated. But, acceding to Sax, Grégoire used the ideas of the revolution itself to protect the cultural heritage of the nation. It was not the objects themselves that should be destroyed and condemned simply because of their patrons. Rather the art works should be preserved and celebrated as symbols of the nation’s artistic genius that would only continue to flourish under the guidance of the Revolution. As Sax explained,

Grégoire saw cultural properties as central to the political life of the country in another sense, however. The Revolution, after all, was remaking the nation without the institutions of the crown and the church that had essentially defined it. How was the new Republic to define its essential quality? Grégoire answered that the essential quality of the Republic reposed in the genius of individual citizens as revealed in the achievements of science, literature, and the arts. The body of artifacts that embodied the best of the people was the quintessence of France, its true heritage and patrimony. Those who were willing to see these artifacts destroyed, or sold abroad as if the nation cared nothing for them he said, were imperiling the most important symbols of the national identity, those things that spoke for what France should aspire to be.

The Church, linked to hereditary privilege and corruption and to the oppression of the people, was condemned and pushed to the social background, but in the midst of the rush to the future, a national respect for the past was installed and became one of the unexpected legacies of the Terror. Of course, dismissing religion is easier said than done, and when Napoléon came into power at the beginning of the nineteenth-century, he readmitted exiled aristocrats and the disgraced Church back into French culture. His actions thwarted ongoing demands that ecclesiastical architecture be destroyed, along the lines of the English Dissolution. Napoléon, ever a nationalist, was distressed over the destruction of the European Medieval heritage and wanted to sake a claim for a French (Gallic), rather than a “Roman” civilization. Predictably, when the monarchy was restored after Waterloo in 1815, there was a wave of nostalgia for the vanished past, swept away by a violent Revolution. As often happens when starting over, the past becomes a source of inspiration. The yearning for a mythic historical stability reached backwards to the Medieval period, safely beyond the rule of the recently deposed monarchy, and as far back as the site of the origins of the nation itself, the time where France began to acquire its unique characteristics. Nowhere could this uniqueness be better viewed than in the architectural remains of Gothic architecture, from cathedrals to churches to forts to castles. The religious buildings that had barely escaped destruction became objects of veneration by the Romantic period of the 1840s, and, in the Salons, faux Medieval troubadour paintings flourished.

Musée des monuments français Today

The realization that an age had passed and a new era was beginning can be traced back to the late eighteenth century when in 1795 actual architectural remnants from the Medieval and Renaissance periods were literally removed from their sites to the Musée des monuments français in Paris. After the Revolution the collection was limited to plaster casts and the collection changed its name to Musée national des Monuments Français. As early as 1831, the famous architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814-1879) toured France making exquisite drawings of French architectural history and in 1836-37 he took a similar tour of Italy. Clearly there was a perceived need to commemorate a culture before it disappeared or disintegrated and the drawings of Villiet-le-Duc were considered exemplary for their accuracy. At his suggestion, the plater cast collection was moved to a new site, the palais du Trocadéro in the vacated grounds for the Exposition universelle of 1878. But not everything was movable and plaster casts could give only so much information about entire structures. It was deemed necessary to catalogue, illustrate, and record the entire historical patrimony of France. This survey would be a massive task undertaken by the famous Mission Héliographique, which for the next fifty years amassed some six thousand images, most of which never saw the light of day in their own time. The Mission’s work would be dutifully executed and catalogued and deposited with the government and forgotten only to be rediscovered in 1980.

The next post will discuss the work of the Mission’s first photographers.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.