NADAR AND THE CELEBRITIES

Gaspard-Félix Tournachon (1820-1910)

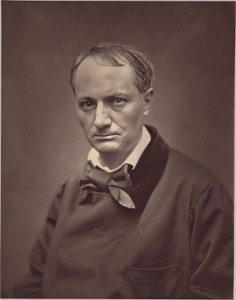

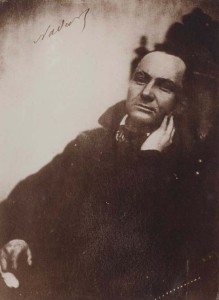

The poet and art critic, Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867), who never met a camera he didn’t pose for, wrote a famous diatribe against photography and its narcissistic pleasures. After a long preamble addressed to M****, Baudelaire launched into what was nothing short of a screed against photography. Comparing photography to pornography, Baudelaire complained in the Salon of 1859, A revengeful God has given ear to the prayers of this multitude. Daguerre was his Messiah. And now the faithful says to himself: “Since photography gives us every guarantee of exactitude that we could desire (they really believe that, the mad fools!), then photography and Art are the same thing:’ From that moment our squalid society rushed, Narcissus to a man, to gaze at its trivial image on a scrap of metal. A madness, an extraordinary fanaticism took possession of all these new sun-worshippers. Strange abominations took form. By bringing together a group of male and female clowns, got up like butchers and laundry-maids in a carnival, and by begging these heroes to be so kind as to hold their chance grimaces for the time necessary for the performance, the operator flattered himself that he was reproducing tragic or elegant scenes from ancient history. Some democratic writer ought to have seen here a cheap method of disseminating a loathing for history and for painting among the people, thus committing a double sacrilege and insulting at one and the same time the divine art of painting and the noble art of the actor. A little later a thousand hungry eyes were bending over the peepholes of the stereoscope, as though they were the attic-windows of the infinite.

In this section of the Salon, “The Modern Public and Photography,” Baudelaire thought that photography–he was referring to portrait photography–was about the love of oneself and self-satisfaction in one’s position in society, but he was also concerned that photography–the machine–would invade the world of painting, fine art. Photography was all very well and good in the world of scientific recording and documentation but, Baudelaire gave neither the medium nor its operators any credit for artistic development. He concluded with a warning, Could you find an honest observer to declare that the invasion of photography and the great industrial madness of our times have no part at all in this deplorable result? Are we to suppose that a people whose eyes are growing used to considering the results of a material science as though they were the products of the beautiful, will not in the course of time have singularly diminished its faculties of judging and of feeling what are among the most ethereal and immaterial aspects of creation?

In an unrelated fragment in his autobiography, My Heart Laid Bare (written 1865/published 1887), Baudelaire wrote the phrase, “cult of images,” “Glorifier le culte des images (ma grande, mon unique, ma primitive passion),”which had nothing in this essay to do with photography but was picked up by Beartrice Farwell’s exhibition catalogue, The Cult of Images. Baudelaire and the 19th Century Media Explosion (1977). Farwell’s exhibition of popular lithographs from the nineteenth century was one of the first of its kind, bringing popular culture into the precincts of art history, heretofore a place for the high arts only. Her work referred to the technology of mass production of photographs and prints which exploded during the Second Empire, feeding what Baudelaire was lamenting, a desire for pictures and a taste for easy satisfaction, entertainment and amusement through the virtual reality of what we today would call an “image world.” Nadar. Charles Baudelaire

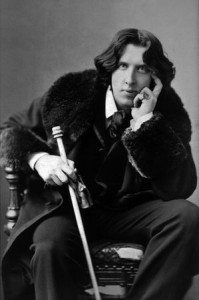

At the time Baudelaire was writing the Salon of 1859 he was shopping The Painter of Modern Life to multiple outlets, and when one reads these two essays (one short and one long), it seems as if Baudelaire had created a contradiction. In The Painter of Modern Life he extolled the merits of the flâneur who observed the crowd and received pleasure from the act of controlled scanning or veiled scopophillia, but in his polemic against photography he argued against freezing that same gaze. But there is an important distinction that Baudelaire focused on, a particular element of photography that he disliked (although he participated in it) and that was the self-fashioning present in the photographic empires of Nadar (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon) and his more industrial counterpart, André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (1819-1889) who specialized in the carte-de-visites. These (self) portraits of Parisians, obscure and well-known, who created themselves as individual and as celebrities, as consumer objects for an eager public to consume their images. Oddly, because, above all, he admired artifice, the self-assemblage and posing and preening in front of the camera by the newly self-aware Parisians offended Baudelaire. Nadar. Oscar Wilde

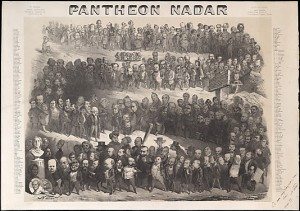

Thanks to the ability of photographers to produce images on a large scale and the willingness of the public to buy photographs, not just of themselves, but of people they did not know, the observers, those who watched the crowd, began to observe themselves and to offer themselves up to the masses. Nadar was probably one of the best photographers for portraiture in France. Indeed his artistry and his sensitivity to his subjects was rare, for he know how to bring out salient characteristics in individuals who cooperated with the photographer in achieving a defining “look.”His understanding of the men and women who flocked to his studio was undoubtedly the result of his apprenticeship in caricature. Nadar knew how to “read” a face. Panthéon Nadar

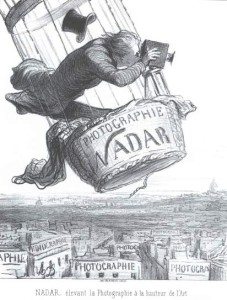

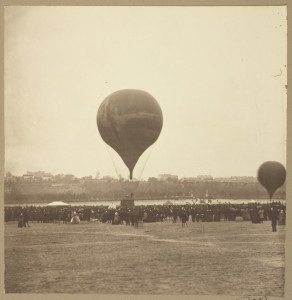

Gaspard-Félix Tournachon began his artistic career in caricature and acquired his nickname tourne adard or “bitter sting” for his biting wit. Over time the nickname evolved: he shortened it to “n à dard” then to “Nadar.” In this small but telling act of self-naming Nadar created a niche for himself as an entrepreneur of a variety of imaginative enterprises. In 1854 he presented the “Panthéon Nadar,” a lithographic group portrait of two hundred and fifty notable Parisians, wittily and well-observed as semi-caricatures. Unfortunately this vast panorama of individual portraits did not sell as well as he had hoped and Nadar followed his younger brother Adrien into photography. But he made sure that he kept his name in front of the public and in 1858, he ascended above Paris in a hot air balloon with the basket full of glass plates and his cameras. Once aloft, Nadar became the first person to take an aerial photograph and became the first photographer to show the earth-bound humans what the birds saw as they winged their way over the city of Paris. Daumier. Nadar Elevated over Paris

In 1863 Nadar constructed a gigantic balloon called “Le Geant” described in R. Ballantyne’s book Up in the Clouds (1869) as The balloon, which is 90 yards in circumference, and has consumed upwards of 20,000 yards of silk in its manufacture, was held down, while filling, by about 100 men, and the weight of at least 200 sandbags. The car was of wicker-work, comprising an inner surface of about 54 square feet divided into three compartments or small rooms, surmounted by an open terrace, to which the balloon was braced.

Nadar and his fifteen passengers, including a prince and princess rose above the earth of the Champ de Mars by 1500 feet, despite the “37 bottles of wine, rifles, crockery, and a cake and thirteen ices.” But as Ballenyne continued, the descent was more eventful than anyone had anticipated: Although they met with no rain, their clothes were all dripping wet from the mist which they passed through. The descent was more perilous than at first reported. The car dragged on its side for nearly a mile, and the passengers took refuge in the ropes, to which they clung. Several were considerably bruised–though, as before stated, no one sustained any very serious injury. Everybody behaved well.

Le Geant

In between all this publicity-generating activity, Nadar photographed Parisian notables. The partnership with his younger brother ended in 1857 when, in a court case, Nadar won the exclusive rights to his own nickname. He set up his independent photographic studio at 35 Boulevard des Capucines in 1861 at the cost of over two hundred thousand francs. The elegant place of business attracted the prominent Parisians who were familiar with Nadar from his caricatures and his arial adventures. But the opening of the studio coincided with the decline in quality. In order to furnish his studio, Nadar had gone into debt and even rented his space to other artists to raise money, such as for the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874. In order to become more profitable, he entered into direct competition with photographer André- Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (1819-1889) and began to manufacture the carte-de-visites. These small multiple photographs, measuring nine-by-six centimeters, were made with multiple masks over the glass plate and the ten card size portraits could be visiting cards, unique to each visitor, and these cards could be collected and traded. Carte-de-visite During Nadar’s peak years from 1855 to 1860, he produced very fine and very simple and straightforward portraits. Using a chiaroscuro to light the face from one side, Nadar concentrated on the face itself, downplaying the clothing and hands for the men. Women were allowed a bit more latitude, as in the portrait of George Sand (1804-1876), no longer an attractive woman. Sand’s stripped dress gently draws attention away from the aging face to her lovely garment. After being able to see their own faces only in mirrors, the generation after the Daguerreotype had become aware of how she or he “looked” or appeared in the “mirror” of photography to other people. The photographic “appearance” could be controlled and compiled through a combination of active agency on the part of the sitter and a sensitive directorial mode on the part of the experienced Nadar. In other words, the client produced, in collaboration with Nadar, a persona to be looked at. What is most interesting about the images produced by Nadar and Disdéri is the extent to which women took advantage of the opportunity to create a social identity for themselves as distinct from their social identity as wives, mothers, mistresses, working girls, and whores. Men, like Baudelaire, who in his youth had been the ultimate self-styler, did little to fashion themselves, as though they needed no introduction. As with one of his portraits of Baudelaire (on the right), Nadar hid the hands and the males are often seen with their hand in their opened coat, a standard pose of the day. Nadar. Charles Baudelaire Styling Himself

The avant-garde painter Édouard Manet (1832-1883) does not look at the camera and seems diffident and reluctant to present himself, despite his elegant suit and erect carriage. Nadar. Édouard Manet

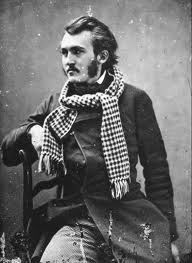

Only the illustrator Gustave Doré (1832-1883) seems to have any flair with his jaunty checkered scarf, an artistic gesture rare among Nadar’s male sitters. Nadar. Gustave Doré

It is no accident that the actress Sarah Bernhardt (1844-1923), who knew how to strike a pose, is among the most beautiful and Nadar worked with the light and dark folds of her drapery to frame her face and shoulders. Nadar. Sarah Bernhardt

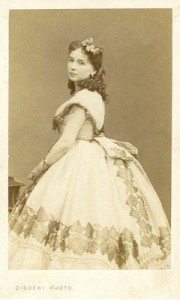

Compared to the artful artistry of Nadar, Disdéri’s images are far more utilitarian and pedestrian. Small and cheap and mass produced, Disdéri’s portraits made him so famous that according to legend, Napoléon III had his portrait taken by the photographer on his way to the ill-fated Franco-Prussian War. Disdéri’s clientele ranged from the general public to to nobility and no one minded the cheapness of what was probably considered a disposable object. Disdéri. Emperor Napoléon III and Empress Eugènie

A mask blocking off all but one exposed area of the plate allowed the camera operator to move the frame quickly from pose to pose, and then the sheet of multiple photographs could then be mounted one by one and sold by the thousands to the public. Today we are used to the circulation of images of celebrities from politicians to movie stars: we know what everyone looks like. But in the nineteenth century, the people did not know the physical appearance of their leaders–tall, imposing, fat, short, unimpressive, heroic–until photographers, such as Nadar and Disdéri, made the prints available for everyone to buy and to mount in photographic albums. These albums were the prototypes of posters of movie stars on the walls of teen age bedrooms or baseball cards lovingly collected over the years. Thanks to the new mass media, the appetite of the public to look and consume other people’s lives and personalities were both whetted and satisfied. Disdéri. Princess Mathilde Bonaparte

One could collect portraits of the Emperor, the Emperor and the Empress, the Empress’s poodle and the Emperor’s mistress, Cora Pearl. The truly discerning collectors would not rest until they had gathered together the entire set of the Imperial family. Disdéri. Cora Pearl

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.