SIX DEGREES OF SEPARATION

Artful Photography

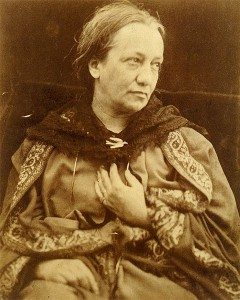

Julia Margaret Cameron and the Eminent Victorians

Julia Margaret Cameron knew absolutely everyone worth knowing in Victorian England or she was connected to someone who knew those she did not know. Her connections to the famous were all the more remarkable in that she was born in India lived on an island off the coast of the English mainland. Her intersection with photography, like so many of the pioneers, was brief, only a few years; but she made her mark as an artist in what was considered by so many as a mere mechanical device. One of the most important early writers on photography, Lady Elizabeth (1809-1893) was married to Sir Charles Eastlake (1793-1865). According the The Victorian Web, Sir Charles became “the President of the Royal Academy in 1850, and in 1855 he was made the Director of the National Gallery. He and his wife, Lady Eastlake, were the great power couple of the contemporary art world.” As prominent as Sir Charles was in his own time, in the annals of the history of photography, his wife is better remembered for her excellent short account of the early decades of the development of photography and for her careful distinction between art and photography. According to Eastlake,

Photography is intended to supersede much that art has hitherto done, but only that which it was both a misappropriation and a deterioration of Art to do. The field of delineation, having two distinct spheres, requires two distinct labourers; but though hitherto the freewoman has done the work of the bondwoman, there is no fear that the position should be in the future reversed. Correctness of drawing, truth of detail, and absence of convention, the best artistic characteristics of photography, are qualities of no common kind, but the student who issues from the academy with these in his grasp stands, nevertheless, but on the threshold of art. The power of selection and rejection, the living application of that language which lies dead in his paint-box, the marriage of his own mind with the object before him, and the offspring, half stamped with his own features, half with those of Nature, which is born of the union — whatever appertains to the free-will of the intelligent being, as opposed to the obedience of the machine, — this, and much more than this, constitutes that mystery called Art, in the elucidation of which photography can give valuable help, simply by showing what it is not.

Her essay “Photography” was written in 1857 in the midst of the switch from the Daguerreotype to the collodion process and from the vantage point of one hundred fifty years later it is clear that the potential of photography to beyond documentation into expression did not even seem possible to Eastlake. Like her contemporary Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) who, two years later, would write his own objection to the idea that photography could ever be art in “The Modern Public and Photography.” A few years later in 1863 a thoughtful daughter would give her mother, who was missing her husband in India, a camera to entertain herself with, and as soon as Cameron took the camera into her hands, she entered into what was mostly a critical debate over photography as art and her pioneering photographs were among the earliest examples of photographs intended to be works of art.

Julia Margaret Cameron

The question that still hovers over her career is–was her famous blurred technique deliberate or was the soft focused prints simply the result of her lack of technical prowess? Helmut Gernsheim, author of the first important book on Cameron, once told me casually that, in his opinion, she simply did not know how to manage the collodion process. There are definite facts to support his theory, for she was known to have struggled with cracked film on the glass plates. As she wrote to Sir Henry Cole (1808-1882) (one of the sponsors of the Great Exhibition 1851),

‘You will see in the Dream the commencement of this cruel calamity…a honeycomb crack extending over the picture appearing at any moment and beyond my power to arrest.’

The Victoria and Albert Museum noted that those who had written of Cameron diagnosed her soft focus approach:

Gernsheim points to a chromatic aberration in her Jamin lens which had a large aperture and fixed stop which made it impossible to control depth of field and obtain sharp images at the close range she preferred for her subjects. Also as Julian Cox points out in Julia Margaret Cameron, The Complete Photographs the plates she used were too large for the size of the lens creating a ‘falling off’ at the edges of the photograph. Her exposure times of three to seven minutes compounded the soft focussing of her images as her subjects were likely to move during the sitting.

In her own account of her work as a photographer in 1874, Annals of My Glass House, Cameron wrote,

..my first successes in my out-of-focus pictures were a fluke. That is to say, that when focussing and coming to something which, to my eye, was very beautiful, I stopped there instead of screwing on the lens to the more definite focus which all other photographers insist upon..

Indeed there is no question that Cameron like the results she obtained and that whether she accidentally stumbled across the soft focus effect while she was teaching herself the process or whether it was her camera, this series of happy accidents combined to give her images an ethereal other worldly appearance that ideally suited the content. The prevailing art form in the 1860s was the Pre-Raphaelite movement which some twenty years after the initial debuts of John Everett Millais (1829-1896) and Gabriel Dante Rossetti (1828-1882) and William Holman Hunt (1827-1910) in 1848, the original small group of artists had many followers. The movement was unique in the nineteenth century in that the Pre-Raphaelite Movement was an avant-garde artistic expression that was quickly vanquished the academic establishment and became a sort of establishment in itself–enormously popular and very much in tune with the needs of the culture.

England, more than any other nation in Europe was impacted by the Industrial Revolution, so much so that the nation has often been used as a model and then applied, incorrectly, to France or Germany, neither of which industrialized as quickly or in the same way as Great Britain. While France and Germany sought to create a modern nationhood in their own pasts, England, already a modern nation, retreated psychologically to its Medieval past for respite from factories and financing and trade and mercantilism and urban squalor and unrest. Particularly popular were the stories of King Arthur, the legendary leader of the Knights of the Round Table in the Age of Chivalry. Le Morte d’Arthur, considered the first novel written in English, was the work of Sir Thomas Malory in 1470. Malory wove together many myths and tales, dating back to the twelfth century, which had evolved over the centuries. But the new version of this timeless bit of noble escapism was written by Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1808-1892) as Idylls of the King in 1859. This extraordinarily long twelve volume poem turned prose into poetry and resonated in the minds and hearts and paintings of Victorian England.

John Waterhouse. Lady of Shalott (1888)

Tennyson, the Poet Laureate of the nation, lived on the Isle of Wight and was a personal friend of Cameron who had become an indefatigable photographers, dragooning her defenseless servants, family members and wary friends into her photographic projects. In fact, the Camerons moved to Freshwater Bay themselves after visiting the poet in his home in Freshwater on the Island. Cameron’s projects can be divided into two categories, portraits of her eminent friends and reenactments of scenes from British literature, especially Idylls of the King. Like the Pre-Raphaelites and their followers, Cameron mined this familiar and nostalgic territory of a very British realm of fantasy and recreated on glass plates scenes from famous stories that were engraved on the nation’s psyche. In writing of the connection between Pre-Raphaelite paintings, Michael Bartram noted, in order to enter into the imaginative world of Tennyson and Shakespeare, Cameron turned away from the precision and clarity of the new invention of Frederick Scott Archer, the sharp focus:

What had been regarded as the glory of Scott Archer’s invention was laid aside in favour of vague outlines and broad tonal masses. In her best imaginative work (always distinct from her justly celebrated portraiture) the aim, as in Rossetti’s watercolour masterpieces of the 1850’s, is brilliantly consonant with the means: a breathtakingly seductive vision to those not irreversibly disdainful of the forms in which mid-Victorian fantasy clothed itself.

Cameron’s portraits were, in their own way, as romantic and as atmospheric as any work of literature or any Pre-Raphaelite work of art. Her female subjects were selected for their similarities to Rossetti’s beauties with their long tresses and pale faces. Many of these lovely women are servants and Cameron, in giving the roles to play or personas to construct, granted them an agency unusual for domestics at that time. Her male subjects seem to emerge from some deep darkness as if coming to view from a great distance. In a series of photographs taken towards the end of his life, Sir John Herschel (1792-1871) looks old and frail and bewildered. Cameron had asked him to wash his hair before the photographic session, something Victorians seldom did, and it is clear that the old man had no idea of how to style his hair and he looked like the quintessential cliché of the “mad scientist.” Tennyson, a younger man, appears to have steeled himself for the many sittings he did with Cameron, even though she too refused to let hm tidy his newly cleaned hair.

It is her reenactments of famous scenes from British literature or folklore, that Cameron was at her most dramatic. As can be seen in the work of Lewis Carroll (1832-1898), amateur theatrics were a common pastime for families as a way to keep both children and adults entertained. Without film of television, the theater would have been one of the major forms of public leisure activities. The middle and upper classes were well educated and well versed in their native literature and Cameron’s staging scenes from Shakespeare and Tennyson would have been familiar to her audiences. Indeed, when she exhibited her photographs in public, they were well received, despite the fingerprints on the plates which transferred to the photographs themselves, the scratched negatives and lack of sharp focus. In fact, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art,

Although she may have taken up photography as an amateur and sought to apply it to the noble noncommercial aims of art, she immediately viewed her activity as a professional one, vigorously copyrighting, exhibiting, publishing, and marketing her photographs. Within eighteen months she had sold eighty prints to the Victoria and Albert Museum, established a studio in two of its rooms, and made arrangements with the West End printseller Colnaghi’s to publish and sell her photographs.

During the 1860s and early 1870s, Cameron joined the appropriate photographic societies, showed every opportunity she could, won medals and awards, while the critics complained about her methods. Cameron was steadfast in defending her work and was fortunate enough to be able to exhibit her work in a small but significant milieu of “art photography,” already established in England. The familiar theatrical presentations of dramatic and heart wrenching scenes of death and farewell that must have moved the English audiences were understood as part of the Pre-Raphaelite mindset of revering the nation’s past. But her promising career was cut short in 1875, when she and her husband returned to Asia and, once she was in Ceylon, Cameron had few chances to concentrate on photography, leaving those who came after her to continue to create and promote art photography.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.