PHOTOGRAPHING THE AMERICAN WEST

PART ONE

Carleton Watkins in Yosemite

In a virtually unreadable book on the discovery of the California territory called “Yosemite,” the first owner of a tourist establishment in what became a national park, James M. Hutchings (1820-1902) gave an account of the discovery of a valley that belonged the native Americans. In the Heart of the Sierras (1888) Hutchings wrote (laboriously) of how the discovery of gold in California brought white miners to the region, encroaching on native lands.

James M. Hutchings. The Heart of the Sierras (1888)

The result was clashes between the miners and other settlers and the original inhabitants and one of the leaders of the white community, Major James D. Savage and his troops followed the “Yo Semites” into unknown territory, where as Hutchings recounted that on on May 5 or 6, 1851, “the great valley opened before them like a sublime revelation.” When the Mariposa Battalion stumbled upon Yosemite, one member of the party, Lafayette Houghton Bunnell (1824-1903) who was a member of the Battalion, later wrote of his experience,

It has been said that “it is not easy to describe in words the precise impressions which great objects make upon us.” I cannot describe how completely I realized this truth. None but those who have visited this most wonderful valley, can even imagine the feelings with which I looked upon the view that was there presented. The grandeur of the scene was but softened by the haze that hung over the valley—light as gossamer—and by the clouds which partially dimmed the higher cliffs and mountains. This obscurity of vision but increased the awe with which I beheld it, and, as I looked, a peculiarly exalted sensation seemed to fill my whole being, and I found my eyes in tears with emotion.

Over a decade later, President Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865), mired in a brutal Civil War, paused in 1864 to give life everlasting to the remarkable valley by marking it off as a place to be preserve and protected, the Yosemite Preservation Act. The first Native American tribe that lived in Yosemite, the Ahwaneechee, were there for four thousand years and it was their descendants, the Miwok Indians objected to the presence of the whites on their lands. The American government, anxious to protect the new state that was yielding gold, ordered Savage (a store owner whose place of business had been attacked by the tribe) to clear the “Yo Semite” territory of the Miwok. Once the tribe was forcibly removed to Fresno, Hutchings heard of tales of a thousand foot waterfall from the Battalion and began to visit the area in 1855. Becoming an authority on California, specializing in Yosemite, he opened a hotel in the valley, the “Hutchings House” in 1864. By that time, Yosemite was to be held in trust for the nation. This the first step in creating a system of national parks in 1916 is often credited to the photographic works of Carleton E. Watkins (1829-1916).

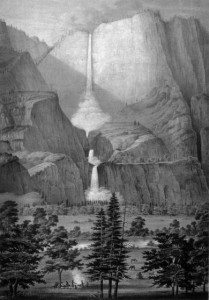

Bit by the gold bug, Watkins had left Oneonta, N. Y. in 1849. In one of the odder historical coincidences he traveled with another individual from the same town, Collis Potter Huntington (1821-1902), who became one of the “Big Four,” the railroad magnates who built the Central Pacific Railroad and the Southern Pacific Railroad. Later Watkins became the unofficial photographer for the railroads and thanks to the patronage of his friend, he could ride the rails for free.Obviously the two young men went their very separate ways, Huntington dying rich and famous, Watkins, bankrupt and insane, but in between, Watkins enjoyed a brief period of fame as a famous and celebrated photographer. The photographer went from a small town in New York to the biggest city on the West Coast, San Francisco, where he learned the collodion process from Robert Vance. After an apprentice period, Watkins headed off for the untouched world of Yosemite to take the first photographs. However, he was not the first to depict Yosemite, that honor goes to Thomas A. Ayres ((1816-1858), who called the valley “Yohimity” and produced a series of lithographs in 1856, the first scenic views to be published in Hutchings’ California Magazine.

Drawing by Thomas A. Ayres

In writing of his experiences, Ayres, who had been on the first excursion into the territory in 1855, reported,

Sitting by our camp fire, the next evening a mass of rocks feel from the cliff near us, loosened, probably, by the previous rain. Starting like a crash of thunder, it came like the tread of an earthquake, while rocks and trees dashed into the valley, whose twilight solemn stillness was broken by the uproar, prolonged by innumerable reverberations. We retired with feelings fully impressed by the awful manifestations of Nature with which we were surrounded;— It would require a much larger space to recount our advertisers in grouse shooting and trout fishing, my wanderings with pencil and sketch book, hunting after the picturesque, admiring the glorious sunrise effects, or the beauties of the declining day from choice points of view. The time passed like a dream, and it was with regreat that we left the beautiful Valley of the Yohemity, bound on an exploring trip to its head waters, far among the snow-clad peaks of the Sierra Nevada, of which more anon.

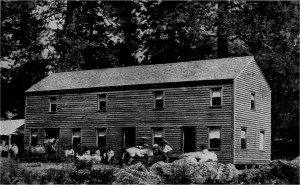

Nor was Watkins the first photographer to go to Yosemite, that honor belongs to Charles L. Weed (1824-1903), who was sent to the area by Robert Vance (1825-1876), the San Francisco who also mentored Watkins. The permanent first house built in Yosemite was constructed in 1855 by Buck Beardsley and Gustavus Hite for Hutchings, and it was Beardsley himself who had to carry Weed’s photographic equipment. Perhaps for his troubles, Weed’s first photograph, taken on June 18, 1859, in the Yosemite Valley was of the “Upper Hotel.”

Charles L. Weed. The “Upper Hotel” (1859)

However, Weed did not make mammoth plate photographs in the Valley until 1865, years after Watkins, whose photographs are considered superior, both in formal composition and in technical ability.

Taken in 1865 in the Wake of Watkins, Weed showed the Entire Tree, unlike Watkins who cut off its Top

That said, photo historian Weston Naef has suggested that several lithographs published in Hutchings’ magazine could have been based on photographs taken in Yosemite by Watkins and that Watkins had visited the area before 1861. The truth will never ben know for the photographers’ archive was destroyed in the San Francisco Earthquake and Fire in 1906. However, it was Watkins who was asked in 1860 to photograph the Mariposa tract and when he made a preliminary tour of the area, he realized that the conventional camera would be inadequate. Therefore, in 1861, Watkins, apparently well informed of the prospects awaiting a commercial photographer in the valley and undoubtedly feeling competitive with Weed, arrived with a remarkable camera, called the “mammoth plate” to accommodate the 18 x 22 inch glass plates. To put this size in perspective, these plates which determined the size of the photographs, were larger than one of today’s laptop.

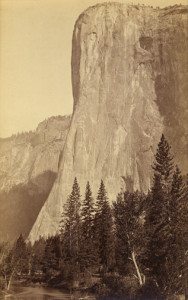

Watkins. The Mammoth Plate Camera

The wooden camera alone weighed forty pounds and the glass plates weighed one pound each, but despite the bulk and weight of the equipment, both camera and sharp edged sheets of glass were fragile. The chemicals necessary for the collodion process also added to the cumbersome equipment that had to be transported over untrodden trails and steep mountain paths. The light was bright and the shadows of tall mountains and great gorges and tall tress were strong and dark: the sky would have to be allowed to bleach out for the long exposures necessary to fully engage the details of the wilderness.

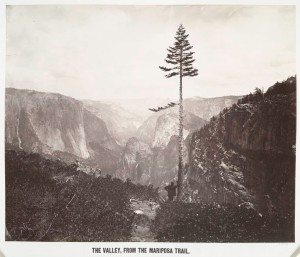

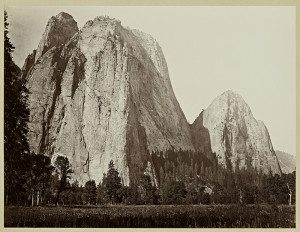

Watkins. Cathedral Rock

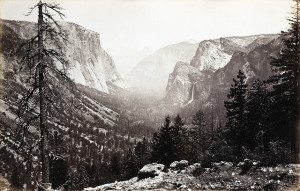

Given the rugged terrain and the precipitous heights of the valley, Watkins went to considerable trouble and exertion to find and acquire what he called “the best view.” He had an eye sensitive for capturing the scenery in all its grandeur, from its great heights, towering rock faces, jetting waterfalls and still glassy lakes. Decades later it was possible for conservationist John Muir (1838-1913) to trace the photographic steps of Watkins, image by image. When Watkins returned from Yosemite, he carried back thirty mammoth plates and a hundred stereoscopic negatives, measuring about 5 x 5 each, a tent and various assorted pieces of equipment, all two thousand pounds of it carried by mules.

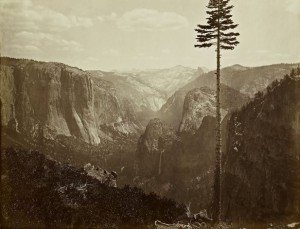

Notice the composition: Watkins invariably divided his structure in the direct center.

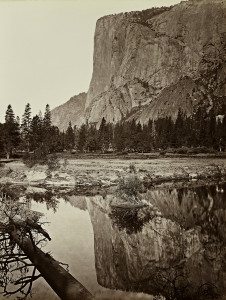

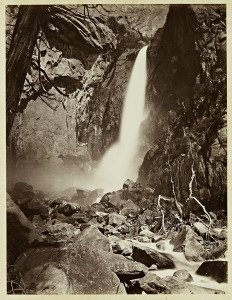

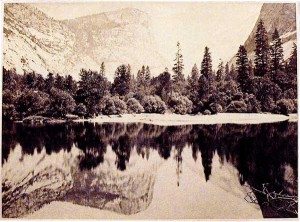

The aesthetic of Watkins was informed by the Hudson River school of painters in the American East and it is their composition that governs his photographs. Like the American painter Thomas Cole, Watkins worked from high vantage points and centers his main points of interest and uses trees as a repoussoir. But he is photographing unseen sights, unprecedented in art and Watkins had to forge his own solutions to difficult problems, the distant view across a wide canyon dissolving in the mist, a perfect mirrored reflection, a waterfall hundreds of feet high shooting down the cliff face in a blurred white plume.

The long exposure turns the moving water into a blur.

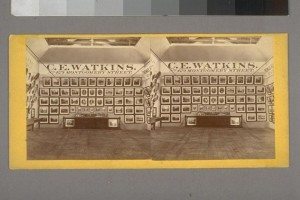

A year later his work was shown in New York at the Goupil Gallery on Broadway and for the first time, the public on the East Coast could see the California scenery they had heard so much about. According to The Guardian in 2011, The New York Times reported in December of 1862,

As specimens of the photographic art they are unequalled, and reflect great credit upon the producer, Mr Watkins. The views of lofty mountains, of gigantic trees, of falls of water which seem to descend from heights in the heavens and break into mists before they reach the ground, are indescribably unique and beautiful. Nothing in the way of landscape can be more impressive or picturesque.

Watkins splits the composition vertically and uses tree to left as repoussoir.

The photography of Yosemite Valley took place during the opening year of the Civil War and became part of a larger impulse to settle the continent from one coast to the other, called “Manifest Destiny.” The famous term was coined by editorial writer John L. O’Sullivan (1813-1895) in relation to the Mexican War. As Sullivan said,

..the right of our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty and federative self government entrusted to us. It is a right such as that of the tree to the space of air and earth suitable for the full expansion of its principle and destiny of growth.

The dream of stretching from sea to shining sea could not be carried out until the question of which new states in the West would be allowed to own slaves and which states should not and a long and blood war had to be fought to settle the issue. Lincoln’s act of setting aside Yosemite was a gesture of hope that the nation would some day be healed and whole. It seems quite possible that the President actually saw the photographs by Watkins that so inspired him because John Conness, California’s first senator showed him the images. Indeed that is the theory of Weston Neff who accounted for Lincoln’s knowledge of a pristine nature and a sanctuary. Another version stated that a congressman saw the New York exhibition and called Lincoln’s attention to it. Whatever the source of Lincoln’s insertion, after terrible battles and many deaths, the unsullied and unspoiled West must have beckoned like another chance for redemption to a war weary public. As soon as the war was over, artists, such as Albert Bierstadt, who had seen the photographs at Goupil’s in 1862, followed Carlton Watkins into the untouched West.

The gridded layers of light and dark are reminiscent of the landscapes that Cézanne would produce decades later in Aix.

Watkins photographed more of the West than Yosemite. In fact, according to the seminal volume on his work from the J.Paul Getty Museum, Carleton Watkins: The Complete Mammoth Photographs (2011), he made over twelve hundred mammoth plate photographs and five hundred stereotype views. However, he made more photographs at Yosemite than any other site, working between 1861 and 1867 and returning in 1872 to work with smaller plates and reworking previous sites. Including his work from 1865-66 with the California State Geological Survey, his album, Photographs of the Yosemite Valley, replicated his journey seventy-five miles into the Valley, shot by shot. The most famous of these images was The Yosemite Valley from the “Best General View (1866) which comprised many of the vistas he made famous in one image, carefully framed and classically composed.

Watkins. The Yosemite Valley from the “Best General View (1866)

Perhaps the high point of the career of Watkins was 1867 when his work was shown at the Paris International Exhibition. In contrast to Édouard Manet (1832-1883), who was rejected from the exhibition and James Whistler who was tucked away in the American section, Watkins won a gold metal for landscape photography. Although the French photographers were producing extraordinary landscapes–Gustave Le Gray’s (1820-1884) work was remarkable–there was nothing as impressive as the mammoth prints of Watkins.

Watkins. El Capitan.

Unfortunately, the French had trouble separating one American from the other and others were given and/or took credit for his work, including Weed. Strangely it was the beginning of a low slow end for Watkins, who would be cheated out of his work in San Francisco, get into financial trouble and have his negatives taken away, had the bulk of his work destroyed in the San Francisco earthquake and fire. Watkins would die, nearly forgotten and would not be rediscovered until the 1970s and not until the 1980s would the entire scope and range of his work be gathered together.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.