The Brotherhood of the Linked Ring

Part One, Becoming Artists

In 1913 Henry Chapman Jones published a very useful book with a rather long title, Photography of to-Day. A Popular Account of the Origin, Progress and Latest Discoveries in the Photographer’s art, Told in Non-Technical Language, in which he, using plain language, described the first major technological breakthrough in photography in almost thirty years–the successful invention of “dry” photography. For decades, photography had been stymied by the cumbersome and complex process of wet plate photography with all its implements and apparatus and chemicals and, most irritating and limiting of all, its long and slow exposure times. But early in the 1870s, a breakthrough was made through the work of two people. It was Dr. Richard L. Maddox (1816-1902), who, in 1871, succeeded in eliminating the troublesome collodion and substituting gelatin which was simply faster and more sensitive to light. His work was picked up by Charles Bennett (1840-1927) in 1877 and what Jones termed the “modern gelatin-bromide” based dry plates began to be manufactured and new cameras were created to accommodate this new technology. The plates could be purchased in a package, stored and used when needed, and, due to the greatly increased sensitivity, the exposure times were reduced from forty to four seconds.

The final step was taken by an American, named George Eastman (1854-1932), who, when he read about Bennett in the British Journal of Photography, immediately understood that the manufacture of such plates needed to be systematized. Eastman invented two significant devices, first a coating machine that allowed each plate to be make in a uniform manner and second a lightweight camera to replace those heavy wooden boxes built to support a bulky pane of glass. When he travelled to England, Eastman realized that Bennett and his partner, Charles Fry, could not fulfill the orders for dry plates efficiently. He returned to America and patented his coating machine and by 1880, he was fulfilling the dream of every photographer–someone else was preparing the plates and the photographer’s time could be devoted to taking pictures. But Eastman had an even bolder vision, to eliminate the plate altogether.

By 1884, with his new partner, William Hall Walker (1846-1917), he began to work on the possibility of employing a lighter carrier for film, such as paper, which could be wrapped around a spool inside the camera. That year, the “Gelatin Paper Dry Plate” was introduced, allowing “amateurs,” that is the public to take photographs at will with no training preparing glass plates for film. Because professional photographers were reluctant to abandon their investment in the old materials and trust film on paper, these people–the amateur public–would be Eastman’s target audience. As practical as the rolls of paper film were, the results were not excellent and images were inferior to the old fashioned glass plate technology. For George Eastman, the goal was to invent a flexible film, independent of any support, and he tasked his chemist, Henry Reichenbach (1859-1957), to develop this product which he knew would revolutionize the business of photography. But it was not a professional chemist who made the breakthrough but a dabbling minister Hannibal Goodwin who stumbled upon a formula for celluloid film (nitrocellulous base) and filed a patent in 1887, reached the finish line first. In the beginning, his achievement was not recognized, especially when in 1889, Eastman patented and received the right to a formula very close to that of Goodwin. These two chemical processes, separated by one ingredient, camphor, would face off in court for decades, but, in the meantime, Eastman’s film was placed in the back of a new kind of camera, patented in 1888 and called “Kodak,” a name made up by Eastman himself.

The Kodak, which was pronounced the same in every language, was oddly described by its inventor as a “little roll holder breast camera,” meaning that the tripod could be dispensed with. A roll of film, capable of taking one hundred pictures, was placed inside of the lightweight box, and the Eastman company would obligingly print the results. The slogan was “You press the button, we do the rest.” Although the camera came first, and the perfected film came a year later, all the elements were in place and Eastman was in control of all the elements: the camera, the roll holder, the film, the processing and developing and the idea that anyone could be a photographer. By the end of the century, the photography “craze” had swept the world and the “snapshot” became the watchword for the new photography.

Professional photographers and serious amateurs, dedicated to the promotion of photography as a fine art, reacted to the democratization of photograph with disdain. Among “amateurs” who were not professional or commercial photographers, the debate over the relationship between art and photography had simmered for years, but the serious photographers were aroused by the sudden entry into the world of photography by unschooled and unserious amateurs, diminishing the very word, “amateur” and lowering the standards for what a photograph should be. For those who practiced photography as a serious vocation, not as a trivial moment of fun, the best way to maintain the high quality of the photograph itself was to elevate the print to a work of art. Before the perfection of the dry plate and of roll film, it was the amateurs who pushed the technology of photography forward, but, at the end of the century, technology had fallen into the hands of corporate businesses and patent offices and any advances were not in the hands of practitioners. The discussion as to the advancement of photography shifted to what qualities constituted the “artistic” elements of a photograph. In the past, a well composed and well executed image would have been sufficient, but by the 1890s, the focus shifted to how and why a photograph could be a work of art.

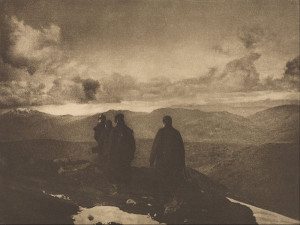

James Craig Annan. The Dark Mountains (1904)

In her article, “Amateur Photographers, Camera Clubs, and Societies,” Becky Simmons noted that in England, a split developed from the veteran photographer, Henry Peach Robinson (1856-1936), who favored not just care towards composing, including combination printing but also the link between painting and photography in terms of subject matter, and Peter Henry Emerson (1856-1936), who was influenced by Impressionism and the relationship between the human eye and the work of art. Photographic experimentation concentrated on creating effects by manipulating the development process so that the resulting image would more closely resemble a watercolor or a print or a painting–a work of art. The ideas was that if the photograph looked like “art,” it could be art. To incorporate these new tendencies on the part of the new breed of art photographers, more camera clubs and photographic societies were formed, such as the Photo-Club of Paris, and The Brotherhood of the Linked Ring, and The Camera Club of New York, all of which were looking to contemporary artists and art movements. In aspiring to elevate a photograph to the artistic level of a James Whistler or a Claude Monet painting or to create a work that would not be out of place within the Art Nouveau or Symbolist movements, these new organizations and their members embarked on the quest to persuade the art public to accept a photograph as a work of art.

Exiting the Photographic Society of Great Britain in 1892, The Brotherhood of the Linked Ring was a secessionist movement, holding “salons,” a term borrowed from the world of painting, from 1893 to 1909. The history of the organization, as recounted by H. Cooper in the 1907 issue, Volume 46 of The Amateur Photographer, began as a dispute over how the work of certain members were displayed by the Society, especially the way in which the technical innovations of George Davison were rejected the the judges. When the artistically inclined members seceded, they were called “children sitting in the market place,” but loyalty to artistic principles were more important than rules. Thus the “linked ring” became their symbol, based on a “gimbal ring, worn two or three at at time, hinged together, so that two people could celebrate their betrothal.

Few of the original members, such as Alfred Maskell, who suggested the linked ring, are known today, but some still have a place in the history of photography, including Henry Peach Robinson, George Davison (1854-1930), and James Craig Annan (1864-1964). According to “The Story of the Photographic Salon. Fifteen Years of Pictorialism,” by H. Cooper, “..the purpose of the Ring was to uphold and demonstrate the artistic possibilities of photography. The Links accepted Zola’s definition of art–“Nature seen through a temperament”–and applied it to camera work. They claimed freedom for themselves and for others, holding that even the violation of a rule might be a distinct charm in the hands of a master..” Cooper went on the note that the first exhibition of the Links was at The Dudley Gallery, but “to a generation accustomed to straight photography the whole thing was barbaric and also sinister. The critic of the Daily Chronicle went back and wrote that the Photographic Salon had the same relation to the artistic Salon that margarine had to butter.” The Amateur Photographer was, in and of itself, an indication of the new direction of amateur photography. As Grace Seiberling and Carolyn Bloore pointed out in their chapter on amateur photography in Amateurs, Photography, and the Mid-Victorian Imagination (1986), this publication and others using the word “amateur” did not begin to appear until the 1880s, addressing itself to “a literate audience with leisure and money to sped on hippies that they did not think of as intellectual pursuits..the new amateur must be understood as a product to only of economic and technological factors but also of the increasing professionalization of activities that had formerly been the province of the cultured person.”

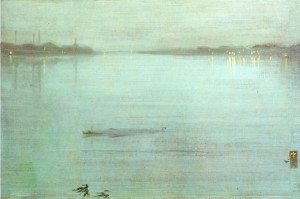

James Whistler. Blue and Silver Nocturne. Chelsea (1872)

The Linked Ring and its Brotherhood made the choice between science and beauty, a direction that was totally in keeping with the fin-de-siècle period in England. Starting with William Morris, who thirty years earlier had renounced the cult of the machine for a return to the historical honesty of the hand-made, reuniting art and craft as it had been in the Medieval period. Morris’s Arts and Crafts Movement expanded from beautiful objects for a household to the entire home itself. Oscar Wilde later coined the phrase “House Beautiful” to refer to the practice of creating an environment coordinated in a total aesthetic or style. The tradition of the home as a “total work of art” moved from Morris in England to Frank Lloyd Wright in America and lived in throughout Europe in the various versions of Art Nouveau. In England, the Arts and Crafts Movement morphed into the Aesthetic Movement, incorporating not only the designers who came after Morris but also the painters, such as James Whistler. British photographers in the Pictorialist movement, such as the members of the Linked Ring, greatly admired Whistler and strove to emulate his smoky nocturnes with their cameras. As the second part of this series on British Pictorialism will discuss, the American George Eastman and other photographic entrepreneurs removed the science of photography from the “amateurs,” leaving the art of photography to those who were part of the Aesthetic Movement.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.