Samuel Bourne in India: Empire in the Making

The way in which the British backed into the idea of empire or imperialism in contrast to colonialism can be viewed by contrasting the contemporaneous reactions of the nation to America and India. The Americans were “colonials,” that is, British people (and other Europeans) who shared a common culture settled land understood as being if not unoccupied at least under developed. These settlements were to be permanent, expanding Europe into the Americas. Unlike Spain which largely sought to exploit the resources of their share of the continent and to extract whatever wealth they could from the land and its people, the British and the French contributed to the growth and development of their territories and extended their own cultures. When the Americans transformed the Thirteen Colonies into a nation, the British reacted with an angry and possessive war, a parent punishing a wayward child. That said, the relationship between the colonies and the mother country was one of equals.

India, was an entirely different matter. This vast Asian continent was an entity that the Europeans could recognize and identify with–a series of kingdoms controlled by all powerful rulers–and there was no attempt to colonize territory. Instead, from the eighteenth century, the goal was imperial, or economic control for the good of the British Empire. The impetus was, therefore, not land but trade and England supported the East India Company in its efforts to establish relationships with those in power in India, the Mughals, to take part in the very lucrative already existing trade in cloth, indigo dye, sugar, tea, and agricultural products. The Empire became truly imperial in its stance towards India when the Mughals waned in power and the East India Company had to step in and establish dominion over India. Of course, given the enormity and complexity of the task of governing an entire continent of alien societies and unfamiliar cultures, “dominion” and “imperialism” were matters of degree. Large portions of India were untouched by the British and lived for most of the Empire out of reach of the Raj, but enough of India was ruled by England which sent government officials and military contingents to maintain order to make of India the “jewel in the crown,” as Queen Victoria expressed it.

The British seemed to have had some dim recognition that the extension of control of trade into outright imperialism needed justification. And indeed, the main reason for the increased British presence in India during the nineteenth century was the stubborn refusal of the continent as a whole to modernize. Once again, the contrast to the colonies in America where “progress” was an inherited cultural value, Indians preferred ancient traditions, which, as important as they were, were of little use to the British who had to compete in a global marketplace of international trade. Part of the rule of India had to be based upon the worthy goal of enlightening the Indians and to bring them into the modern world. The attitude of the English was one of unquestioned superiority towards these dark skinned people whose folk ways could be tolerated as long as they cooperated with the larger mission of the Empire. T. B. Macaulay, who spent four years in India serving the Empire, put the attitude of the British very nicely in 1835 when he stated that English must be imposed upon the Indians,

We have to educate a people who cannot at present be educated by means of their mother-tongue. We must teach them some foreign language. The claims of our own language it is hardly necessary to recapitulate. It stands pre-eminent even among the languages of the West. It abounds with works of imagination not inferior to the noblest which Greece has bequeathed to us, –with models of every species of eloquence, –with historical composition, which, considered merely as narratives, have seldom been surpassed, and which, considered as vehicles of ethical and political instruction, have never been equaled– with just and lively representations of human life and human nature, –with the most profound speculations on metaphysics, morals, government, jurisprudence, trade, –with full and correct information respecting every experimental science which tends to preserve the health, to increase the comfort, or to expand the intellect of man. Whoever knows that language has ready access to all the vast intellectual wealth which all the wisest nations of the earth have created and hoarded in the course of ninety generations. It may safely be said that the literature now extant in that language is of greater value than all the literature which three hundred years ago was extant in all the languages of the world together. Nor is this all. In India, English is the language spoken by the ruling class. It is spoken by the higher class of natives at the seats of Government. It is likely to become the language of commerce throughout the seas of the East.

This casual assumption of superiority as the foundation of Imperialism was briefly challenged by the Indians in 1857 in what is now termed, in India, as the “first war of independence,” and what is called in England as the “India Mutiny.” The doctrine of Macauley had only intensified over the decades and the British Empire was aggressively taking over lands and insisting on enveloping India with dominance not only economically but also politically and culturally. There rebellion was not so much about the tightening of the Empire’s grip on the economy but the insistence of Westernization and the very real threat of having long held religious beliefs wiped out by a small army of well-intentioned missionaries and an ever expanding array of laws intended to break apart the interlocking elements of a social system governed by the laws of caste. The Mutiny was characterized by desperate violence on both sides and ended, predictably, with the crushing of the rebellion by the technologically superior British who, it must be said, did not exhibit high ideals of civilized behavior during the struggle. The outcome was the abolition of the East India Company and England began to rule India directly and the continent came firmly under the control of what was the greatest Empire of the modern era.

It is into this new situation of a brutal and self-serving Empire that photographer Samuel Bourne (1834-1912) arrived in India in 1863. As the British moved in, with an eye towards colonizing their imperial prize, photographers inevitably followed, equipped with the cumbersome wet-plate kit and carrying the imperial eye, the camera with a magisterial gaze. Bourne, who had trained in the picturesque regions of English Lake country and the Highlands, was an adventurer, one of many who flocked to India seeking their fortunes in a land now subdued and tamed. Part one of the Indian adventure was already over and the contest of India was more or less complete in the 1860s. A decade earlier in 1857, photographer British photographer Felix Beato (1832-1909) had hurried to India and captured the aftermath of the Mutiny. His stark 1858 image with its angry imperial title, The Well of Cawnpore Where 2,000 English Were Barbarously Murdered, shows the site on one of the most horrifying events of the Mutiny, the slaughter of seventy-three women and one hundred twenty-four children by Indian mutineers. The “Well” refers to a literal well where the butchered bodies of the murdered English were dumped. This event was seared into the collective consciousness of the British and the photographs and prints of the infamous site were used to both shame and humble the Indians and to justify the necessity for the rule of the civilizing Empire.

![[The Well of Cawnpore Where 2,000 English Were Barbarously Murdered]; Felice Beato (English, born Italy, 1832 - 1909), Henry Hering (British, 1814 - 1893); India; 1858 - 1862; Albumen silver print; 22.2 x 30.3 cm (8 3/4 x 11 15/16 in.); 84.XO.421.50](https://arthistoryunstuffed.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/11176301-1-300x220.jpg)

[The Well of Cawnpore Where 2,000 English Were Barbarously Murdered]; Felice Beato (English, born Italy, 1832 – 1909), Henry Hering (British, 1814 – 1893); India; 1858 – 1862; Albumen silver print; 22.2 x 30.3 cm (8 3/4 x 11 15/16 in.); 84.XO.421.50

Image courtesy of Getty Images

Samuel Bourne. Cawnpore: The Memorial Well, with the Cawnpore Church in the Distance (1865)

As Sean Willcock explained in his 2015 article “Aesthetic Bodies: Posing on Sites of Violence in India, 1857–1900,”

Such was the grisly tomb that became the focus for an obsessive project of memorialisation and sanctification following its discovery by the horrified British. European aesthetic practices – from picturesque landscape design to sculpture and touristic photography – were mobilised to reframe the unsettling emblem of imperial vulnerability.

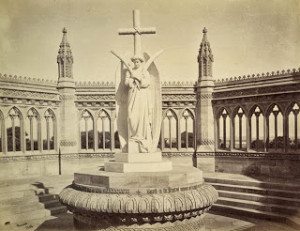

At the time Beato photographed the Well, the place of terror had not yet been transformed, but when Bourne recorded the same place, it had been transformed into an impressive memorial. There is nothing even remotely Indian about the Memorial, designed by Italian artist Baron Carlo Marochetti, with its English and Christian angel, eyes downcast in “heathen” lands, and soul uplifted by the cross. The screen behind the angel is pure Gothic, reflecting the revival currently in vogue in England, and the inscription around the edge of the Well itself reads, “Sacred to the perpetual memory of a great company of Christian people chiefly women and children, cruelly massacred near this spot by the rebel Nana Sahib, and thrown, the dying with the dead, into the well beneath, on the 15th of July, 1857.”

The story of the Mutiny is a tangled tale of the outright misrule of the British East India company, the refusal of the British to accept or tolerate non-Christian beliefs in a continent dominated by Hinduism and Islam faiths, and the careless mindset of the British government that had, up until that time, allowed a commercial enterprise to operate in the name of empire and commercial imperialism. The Sepoy troops that mutinied served under the interestingly named Honourable East India Company and numbering some 370,000 were under Company control, and led by some 34,000 British trained military officers. This untenable situation, remedied when Victoria became not only Queen but also Empress of India, could not continue after the long and bitter Mutiny was suppressed. The actual site of the massacre of the women and children, photographed by Bourne, was, in fact, a compound built by a British officer for his Indian mistress, the Bibighar or “House of Women.” For decades, British men had been adventuring in India, largely without the “civilizing” company of white British women. The largely male society sought to suppress intimations of homosexuality which inevitable arouse in such a homosocial society. In India, Englishmen learned the Indian sports of pig sticking and polo, activities that were guaranteed to improve male physique especially the male buttocks, which would be greatly improved by rigorous riding. To ward off male to male attractions an antidote was in order, namely local women, whose Indian skin and faith would render them forever outside the acceptable boundaries of British decorum, a recipe for heartbreak and tragedy. It was probably on accident that the leader of the Mutiny, Nana Sahib, brought the British women and children to this place tainted by sexual desire. Bourne’s image of the memorial shows the entire site–once a harem–from a distance that allows his camera lens to take in the entire vista which he measures by posing three Indians subjects in the middle ground. Posed in a harmonious triangle and surrounded by sentry like newly planted trees, the “natives” are shown as satisfying suborned and passive, adding a touch of reminder to the now complete British control of India. The entire park has been wiped clean of the memory of its original function, a place for mistresses, and has been turned over to official British male rule with Indian males arranged in satisfyingly humbled positions.

Samuel Bourne. Memorial Garden, Cawnpore (1865)

In understanding the impact of the Mutiny and the entry of the official British government into India, the now official “jewel in the crown,” one can do no better than Harriet Martineau’s (1802 – 1876) British Rule in India: A Historical Sketch. Written in 1857 when the Mutiny was still unsettled, this book is an example of early sociology by a pioneering sociologist who had previously studied the alien land of America, Society in America (1837). She followed up her commentary on India with Suggestions Toward the Future Government of India (1858) when the uprising was apparently under control. Although Martineau was a believer, as were virtually all English people, that England had a mission to civilize India, she was critical of the lack of tolerance for religious beliefs that led to the uprising when Muslim troops were subjected to pork fat. It was part of the British mindset that India needed to be “reformed,” and Martineau cautioned that this task should not be undertaken in ignorance and that perhaps the Indians could both rule and improved themselves under British guidance. In Suggestions, she cautioned,

The commonest remark made in all companies and in all periodicals within the last half-year, has been that scarcely anybody knows anything about India. Outside of the small Anglo-Indian society collected inLondon and about the Company’s colleges, there is next to no knowledge tat all about the history , thee geography, or the politics of Hindustan. So says the Times newspaper; and such is the frank acknowledgment of candid personal whom one meets every day asking for knowledge. The mutiny has helped some of us to some of the geography of the country; but its history and political condition are not to be so easily picked up: and it may be confidently said that no honest constituency in the kinsmen would present to be qualified to decide, through its representatives, on the best method of dealing with such a dependency as India.

It would be the next generation of photographers–such as Samuel Borune–who would come to a newly peaceful and tamed corner of an ever-increasing empire and continue the taming and the framing, if you will, through photographic narratives of an alien and exotic land of fantasy and fascination and, of course, continued and willful misunderstandings as fictionalized in E. M. Foster’s Passage to India (1924) and Paul Scott’s The Jewel in the Crown.The Raj Quartet (1966) books which were sage critiques of British rule in India.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.