The British Look at the Chinese: The Anthropological Gaze

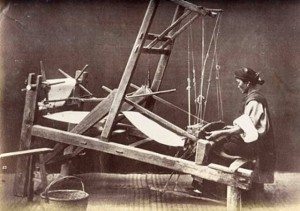

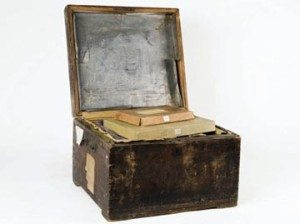

When John Thomson (1837-1921), a native of Scotland, arrived in China, Great Britain had just militarily and politically and diplomatically defeated this huge nation, going to war, not once but twice, over the lucrative matter of the opium trade. Unlike many photographers in foreign lands, Thomson did not establish a studio or a gallery in a Chinese city, and, from 1868 to 1872, he was always mobile, often on the streets, hauling his heavy equipment and bulky materials over the countryside and taking long journeys within the country. Like so many photographers abroad during the wet-plate period, the photographer was a beneficiary of the colonialism of the time, for it would have been extremely difficult if not impossible for him to gather the photographic record of China without the laborers who fetched and carried his equipment on his behalf. He made hundreds of glass plate negatives, ranging in size from 10X12 to 12X16 inches and most of these plates survive today, can still be used for printing and can be viewed in the Wellcome Collection in London.

Glass Plate Negative of Prince Gong

What Thomson found in China was a territory so vast he could hope to traverse only a small fraction of coastal terrain, and Thomson, who considered himself an expert on China, never learned the language and absorbed much of his information through the simple practice of observation and writing down about what he saw. The camera, for Thomson, represented an irrefutable record keeper and he is often understood as an early “photojournalist.” When he returned to Britain, Thomson expended much effort in educating the British people on their newest colonial “possession” through lectures and albums and even reproductions in illustrated magazines. More recent discussions of Thomson view him through the perspective of the colonialism and imperialism of his time. In the article “Through the Looking Glass: Photography, Science and Imperial Motivations in John Thomson’s Photographic Expeditions,” Geoffrey Belknap argued that “Thomson’s lens were embedded in practices of taxonomical colonial encounter.” In arriving in China after the Second Opium War, Thomson constructed “a visual and textual language of racial, economic and gender differences which was articulated through the publications of his photographic interactions with colonial spaces. Thomson acted as an imperial agent, with his camera as his tool of visual acculturation and the travel book as his medium for expressing this gaze.”

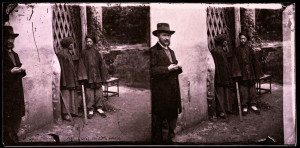

John Thomson in China in 1871

Like most of the nations of the “Far East,” the China of the 1860s was backward and rural, lacking in Western technology, now the new measure of “progress.” For centuries China had been isolated by distance. Bits and pieces of Chinese culture floated to Europe–gunpowder and noodles and the compass and paper bank notes and movable type and restaurants. Until the seventeenth century, China was as cultivated as Europeans. As naval technology progressed, it became possible for trade to be established between China and European nations which were enamored of the fine porcelain, or “china,” and the excellent tea. Although the English developed a “China Mania” for Chinese design and architecture in the mid to late eighteenth century, the term “chinoiserie” to refer to Chinese motifs was apparently not coined until 1911 . The problem that developed between China and England is readily apparent for there is a lack or reciprocity in trade. England had little that China wanted beyond good hard shiny currency, preferably silver. Like Japan, China had steadfastly resisted Western influences but, by the nineteenth century found itself unable to effectively engage the British Empire which was determined to exploit the huge market, waiting for English imports.

The import that could become necessary to the Chinese was an Indian product, opium, a powerful and addictive drug. Once the buyer was “hooked” on the dust of the poppy, this individual would spend any amount of money to maintain what would be a life-time of addiction. Few products have such profit and longevity. Few consumer goods demand to be replaced on a regular and frequent basis. Opium was a virtual gold mine for the English, the drug suppliers, who found it easy to cut the Chinese middle men, the dealers, in on this lucrative trade, which had the added benefit of lifetime users. Everyone made money but the Chinese government which saw the coastal cities of the Canton province plagued by a crippling drug and crippled population of opium-addled users. Alarmed, the Chinese Emperor struck back at the traffic in drugs and the British, apparently disinterested in the social costs of addiction to the Chinese, were determined to maintain the trade and were willing to wage a punitive war in this cause.

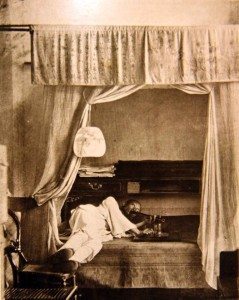

John Thomson. Opium Smoking in China

The result were two ruthless wars, The First Opium War (1839–42) and the Second Opium War (1856-60), between the British Empire and the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912). In between these wars, England also put down the Mutiny in India. It is at mid-century, that it became clear to anyone observing the rising tide of imperialism that the British were now pitiless empire builders, amoral actors without mercy. To complete the humiliation of the Chinese and to seal its dominance over the now prostrate dynasty, England attacked Beijing in 1859 and looted and sacked the Summer Palace in 1860. The action, joined by the French, was in reprisal for the Chinese who had captured, tortured and killed French and British delegates negotiating a treaty to end the War under a flag of truce. The French were incensed enough to demand that the Forbidden Palace, the home of the Emperor, also be destroyed, but the British convinced them to be content with merely destroying the Summer Palace, which was on fire for three days and nights.

A Royal Engineer, who was present at the destruction, Charles George Gordon, later wrote, “You can scarcely imagine the beauty and magnificence of the places we burnt. It made one’s heart sore to burn them; in fact, these places were so large, and we were so pressed for time, that we could not plunder them carefully..Quantities of gold ornaments were burnt, considered as brass. It was wretchedly demoralising work for an army.” The plundered items eventually found their way into British, French and American collections and to this day, the Chinese, who recently rebuilt the Old Summer Palace, seek to recover their property. The British settled into a newly subdued China, basing themselves in Hong Kong, leaving the hard work of government to the Chinese, but this autonomy was an illusion. The Chinese nation was denied full sovereignty or the right to govern not only itself but also those foreigners who lived on its soil. The British were truly imperious, above and exempt from Chinese law. Thus began what was for the Chinese, a “century of humiliation,” ended only when Mao Zedong took power in 1949. John Thomson was the photojournalist who captured this backward and humiliated China, a China, that unlike Japan, resisted modernization and industrialization, a costly decision in the long run.

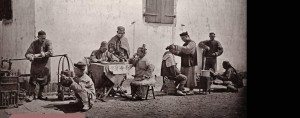

John Thomson. From Illustrations of China and its People (1874)

In his 1898 book, Through China with a Camera, John Thomson explained a culture dedicated to tradition not to change or progress:

“Signs of forward movement, however, have not been wanting, but they are solely due to pressure from without, not infrequently applied at the point of the bayonet. There has been spontaneous dance. The effort of the Chinese have been spent, and their resources exhausted, in futile endeavors to safeguard their ancient institutions…the Chinese today place implicit faith in their time worn moods of training for germinate service, civil and military.”

Thomson’s book reads like a textbook on China, rather dull, fact-filled, but informative, droning on like a conscientious lecturer. Of course, as the quoted passage suggests, his discourse reflects the prevailing European perspective on China as being mired in the past and refusing to move into modern times. Given that China’s experience with modernity was opium addiction, it is understandable that the Qing dynasty sought to protect itself from an invasion that was the equivalent of a cultural and social death threat. But even though he decries the reluctance of the Chinese to accept change, the goal of Thomson is not to make the case for British colonialism in China, a condition he takes for granted, but to divide the Chinese population into the now-familiar “types,” from scholars to shopkeepers. A hybrid of anthropology and sociology and journalism, the book is lustrated with his photographs and the images are put into the social context of life in Hong Kong (“Honking,” as Thomson spells it) where opium smoking is a part of ordinary life, taking place out in the open.

Music halls, according to Thomson have an altar to the god of pleasure at their entrance. Nearby “half a dozen of the most fascinating of the female singers were seated outside the gate; their robes were of richly embroidered silk, their faces were enameled, and their hair bedecked with perfumed flowers and dressed, in some cases, to represent a teapot, in others, a bird whispered wings on the top of the head.” When Thomson uses the word “enameled” to describe the face of a Chinese woman he is not exaggerating. Chinese women covered their faces with thick white paste, which, when hardened, was then polished. Color was then applied to the cheeks and lips and even to the palms of the hands. Later on Thomson describes these faces as “painted until they resembled their native porcelain ware.”

John Thomson. A Manchu Bride in Beijing

In many ways, Thomson takes the armchair reader on a tour of Chinese neighborhoods and the book often reads like a tourist guide, meaning that it is part of the growing genre of travel literature. This books appears to be written in chronological order of his travels and the photographer meanders from Hong Kong to some inland villages to the port city of Canton to the Portuguese city of Macao to the island of Formosa to Shanghai and beyond to the Great Wall itself. Thomson describes every kind of occupation and industry and even explains to the English reader where the famous Chinese silks come from, starting with the worms. He describes the degraded situation of the ubiquitous peasant class and notes the terrible poverty viewed at every turn. One recalls that it is from the Canton region that so many Chinese man migrated to California to build a railroad for Mr. Stanford and his friends. Thomson wrote extensively on the low wages for artisans in Canton and spent a few pages on the artists who designed the elaborate patterns on shoes and those who embroider the delicate pairs for men and women. “It will be seen from the foregoing notes that skilled labour is so cheap in China so to give artisans a great advantage in all those various branches native industry which find a market abroad; and this will one day refer the clever, careful and patient Chinaman a formidable rival to European manufacturers hen he has learned how to use machine in weaving fabrics of cotton or silk.”

Thomson was a discerning and noticing traveler and, as the book progresses, one begins to understand why he was considered a photo-journalist for his rather spare writing is pithy and descriptive, allowing the British or Scottish reader to visualize, with the aid of the images scattered among the pages, a strange and alien culture. But he is not without empathy for the extreme and horrifying poverty he observes in the imperial city of Beijing (Peking in his day) and it is possible to watch his mind already turning to his next project, the poor of London, another great city with extreme contrasts of wealth and squalor. “The shops in Peking, both outside and within doors , are very attractive objects..I could discover evidence of distribution of the wealth of the official classes in all those shops which in any way supplied their wants, or ministered toothier tastes. On the other hand, signs of squalor and misery were apparent everywhere n the unwelcome and uncared-for poor; all the more apparent, perhaps, when brought face to face with the tokens of wealth and refinement..” In his conclusion to his sort but remarkably board portrait of China, Thomson wrote, “Poverty and ignorance we have among us in England; but no poverty so wretched, no ignorance so intense as are found among the millions of China.” His statement is not one of contempt but one of pity, empathy and despair, a curious ending for a voyage of discovery into the heart of the Orient.

Thomson’s Chest for Glass Plates

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.