Nineteenth Century Imperialism in the Middle East

Part One: James McDonald and the Ordnance Survey

“It is in fact with the Bible in his hand that a traveller ought to visit the Holy Land.”

Viscount François-René de Chateaubriand. Itinéraire de Paris à Jérusalem (1811)

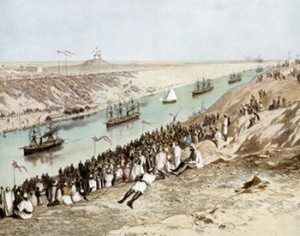

Here’s a question for you: what is the connection between a college graduation, the Suez Canal and the terrorist group ISIS, also known as ISIL? The answer lies in the political condition of the Ottoman Empire in the Levant in relation to the European powers, which were circling like vultures of a still stirring corpse as early as the beginning of the nineteenth century. During the entire nineteenth century, it was easier to pick off chunks of the recumbent empire than it was to instigate a direct war and the European powers allowed their ally during the Crimean War to continue as an ineffective shadow of its former self. If nothing else, the continued existence of the Ottoman Empire was a check on the ambitions of another circling vulture, the rising Russian Empire. The extent of the inability of the Ottoman Empire to respond to the incursions or invasions into its territories by its fellow empire makers, France and England, can be measured by the weak response of Turkey to the French usurpation of Egyptian lands and Egyptian peoples during the building of the Suez Canal. Ever since Napoléon scouted Egypt in 1798 and claimed it as his conquest before he returned to France, the French were aware to the possibility of cutting a canal across the Isthmus to connect the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. Teams of Napoléonic engineers were sent out the explore the feasibility of such a project but incorrectly concluded that the relative sea levels were too incompatible for such a connection. It wasn’t until 1847 that more modern and accurate surveys revealed that the levels of the Mediterranean and Red Seas were similar and the dream of a canal was resurrected.

In the intervening decades, England had surged ahead of France and began to build a substantial empire, with India firmly in the hands of its East India Company, and Great Britain eyed French activities in Egypt warily. For England, Egypt was an important land bridge to India. Indeed, due to the Anglo-Turkish Trade Treaty of 1838, the British Empire had strong trade interests in Egypt, especially in its cotton, accounting for a lion’s share of the imports and exports of its subordinated partner. And in fact, by mid century, the strategic territory was semi-independent from the Ottoman Empire but under the dubious protection and control of England and France. England, ever interested in transporting its goods across Egypt, built a railroad, the Alexandria-Cairo-Suez, completed in 1857. In response to the English activities in Egypt, the French proposed the long dreamed of Canal across the Suez. Perhaps wisely, the British stood back and allowed the French to dig the massive trench, intending to claim its rewards in increased trade while spending no English money in the process. During the messy and corrupt business of building the Canal, the British protested the sheer scale of theft of lands from a “simple people” and the outright slavery of the Egyptian workers in the service of the French government of Napoléon III. The Emperor was related by marriage to the former diplomat, Ferdinand de Lesseps (1805-1894),who was in charge of financing the project and fashioned a favorable agreement with the viceroy of Egypt, Said Pasha. Pasha, in return, granted the necessary lands along the canal route and needed the quarries for materials and the human labor, all provided without cost to the French.

Although the actual construction of the Canal began in 1861, the time of the industrial revolution, the conditions for workers was the same as that of ancient Egypt under the Pharaohs–they worked with their hands, no machines and no salaries. Machines were expensive and cheap labor, four-fifths of which worked for free under the threat of government violence, greatly increased the future profits for the French, especially if those who toiled used the same methods employed under Pharaoh Senusret III in 1850 BCE. Igniting a media campaign, the British used the French exploitation of Egyptian labor as a wedge between the French and the rest of the civilized European world. Eventually, public opinion and threats from the Ottoman Empire, the Porte, forced the Emperor and his minions to pay the workers a living wage in 1863 and the increased expense forced the French to use and even invent machines to build the Canal. The Egyptian government went into such debt breaking open the Isthmus that it sold the majority of its shares to England and France, who now, for all intents and purposes, owned the Suez Canal when it opened in 1869 in a ceremony on November 17–surely the high-water mark of the Second Empire. At the request of the viceroy, the composer Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) wrote the opera Aida in 1871 and its famous triumphal march used for college graduations to this day.

Opening the Suez Canal, November 1869

Historically, Egypt was not the only Middle Eastern territory of the Ottoman Empire where England and France vied for control. The two nations also took advantage of the lax control of Turkey over the Levant or the modern nations of Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria, and Iraq. This is the medieval territory of the “caliphate” or parts of the old Abbasid Caliphate, from mid eighth century to the mid thirteenth century, predating the Ottoman Empire. By the mid nineteenth century, all of these nations were within the imperial sphere of England and France, as tolerated by the Ottoman Empire. The extent to which this modern imperialism was self-assured and unchallenged can be quite literally illustrated by a major photographic activity in the area, the Ordnance Survey of the Peninsula of Syria, which included Jerusalem. This massive military and biblical examination of the “holy land” was undertaken by the British Empire between 1864 and 1869. “Ordnance” means exactly what the word states, weapons, ammunition, guns, cannon, and other military supplies. The result of this Survey was hundreds of photographs, most taken by a sergeant, James McDonald, in the service of his country, a military reconnaissance acting under the guise of biblical antiquarians in search of archaeological sites.

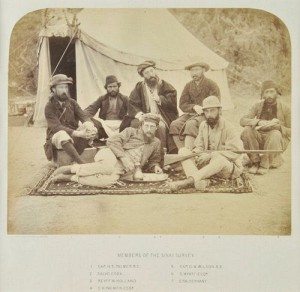

James McDonald. Members of the Sinai Survey

(The Ordnance Survey of the Peninsula of Sinai) (1869)

In 1873, the British publication The Athenaeum announced that the Ordnance Survey of the Peninsula of Sinai made by Capts. C. W. Wilson and H. S. Palmer, R. E., under the direction of Col. Sir Henry James, R. E., Director-General of the Ordnance Survey. 5 vols. had completed its publication, explaining that three of the five volumes, containing the photographs, had been published two years earlier.The newspaper noted that the idea of the Survey was instigated by religious figures who wanted to explore what was then called “the Holy Land” to locate the major sites mentioned in the Bible. The significance of such a religiously inspired “survey” can be better understood not only against the backdrop of the Suez Canal in progress and the recent publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species in 1859, a book that challenged conventional Christian assumptions of faith with suggestive science. Photographs, such as those taken by McDonald, of Biblical sites were thought to be a form of irrefutable proof of the final truth of the events related in the Bible itself. Today, as Suzanne Richard pointed out in Near Eastern Archaeology: A Reader (2003) pointed out, the fields of Biblical archaeology and Palestinian archaeology, i.e., religious studies and historical studies, while overlapping in spheres of interest, are separate in methodologies, but in the dawn of archaeology, there would have been no distinction between the Bible and actual history.

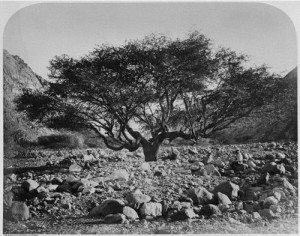

James McDonald. Seyal (Shittim) Tree, Mouth of Wady Aleyat (from the album “Ordinance Survey of the Peninsula of Sinai (1869)

The Ordnance Survey sprang out of an innocent desire on the part of English scholars to find the fact of the Bible. Sponsored by Queen Victoria, the Palestine Exploration Fund, or the PEF, was set up in 1865 by British and American scholars who needed accurate maps and a precise exploration of the Holy Land. According to the 2013 book Hebrew Bible / Old Testament. The History of Its Interpretation. III/I: From Modernism to Post-Modernism, the full title of the PEF was “Palestine Exploration Fund. A Society for the Accurate and Systematic Investigation of the Archaeology the Topography, the Geology and Physical Geography, the Manners and Customs of Holy Land for Biblical Illustration.” The author Steven W. Holloway also noted that “From the beginning, the PEF operated in a place and time when Victorian Protestantism marched openly in step with British imperial pursuits.” When the French built the Suez Canal, the PEF, founded by Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, Dean of Westminser and Regius Professor of Ecclesiastical History at Oxford, provided excellent cover for the Ordnance Survey, which produced “no nonsense military instruments, virtually devoid of biblical allusion. This pattern of military cartography under camouflage of biblical research would be repeated several times by the PEF”..or what could be termed “Governmental backing in the prosecution of Kipling’s “Great Game,” or the imperial contest between England and Russia.

In her 2003 essay, “Mapping Sacred Geography: Photographic Surveys by the Royal Engineers in the Holy Land, 1864-68,” Kathleen Stewart Howe noted that the official survey photographer Sergeant James McDonald posed the Officers of the Royal Engineers of the Ordnance Survey with the PEF scholars of Oxford and Cambridge, who were in the dubious business of “claiming” the Holy Land “as a uniquely British possession.” As the author pointed out, echoing Holloway, “Surveying the East, in this case, the birthplace of Western Christianity, united military surveyors, philologists and biblical scholars in a quasi-military campaign articulated in terms of the great intellectual project to know the Orient. The taking, organizing, collecting and viewing of the photographs was an integral part of that project.” Howe recognized the tangled alliance between photography and “areas of belief, intellectual inquiry and imperial claim.” As early as 1856 the Engineers had prowled around Jerusalem, as if they owned the territory outright, examining buildings and and bridges, with the intent of modernizing where needed, locating sites where soldiers could drill and even “Recording the effects of the explosion of gunpowder in different positions.” Keep in mind that all this British activity, from explosions to photography, was undertaken in the heart of the Ottoman Empire with apparent impunity.

Given that the meaning of McDonald’s photographs were purely documentary and intended for the combined military and religious contention that, as the Archbishop of York, William Thomson expressed it in 1875, “Our reason for turning to Palestine is that Palestine our country. I have used the expression before and I refuse to adopt any other,” these images by McDonald are devoid of the poetry expressed by Eadweard Muybridge in Yosemite and lack the flights of imagination played out by Timothy O’Sullivan in the barren deserts of Western America. McDonald was required to record the territories of Jerusalem and the Sinai Peninsula for two purposes, military information and religious convictions, or as Howe eloquently expressed the role of the photographs as “graphic articulations of a physical possession, defined and justified by a pervasive geopiety centre on the lands of he Bible; at the same time, they reinforce that attachment to sacred place with is geopiety.”

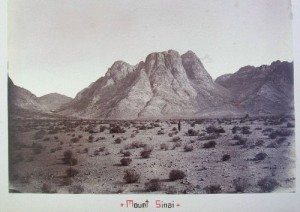

James McDonald. Mount Sinai. PEF – Palestine Exploration Fund (1868-1869)

Little is known of McDonald himself beyond the fact that he was a Color Sergeant who had been selected for the task due to his dual expertise in surveying and photography. The Royal Engineers were among the first military units that instituted photography as a basic skill taught to the specialists. McDonald, however, was primarily a surveyor, his main task for the Palestinian Exploration Fund. Like all the engineers, he was part of a support group, providing expertise to the scholars, but when he wasn’t engaged in the Survey itself, he was expected to take photographs of important religious sites. In his role as photographer, McDonald worked directly under the personal supervision of the Director General of the Ordnance Survey, Major General Sir Henry James, who had been instrumental in raising the public subscriptions or funding which paid for the Survey and its staff, including the photographer. Sir Henry even used his own money to purchase the necessary photographic equipment and supplies, and the photographs taken by McDonald should be considered as supplemental to or illustrative of the (military) maps produced by the Survey party. As James explained, “This map is especially required by Biblical scholars and the public, to illustrate the Bible history, and to enable them, if possible, to trace the routes which were taken by the Israelites in their wanderings in the wilderness of Sinai and to identify the mountain from which the Law was given.” Despite the private/public hybridity of the mission of the Survey, the images taken by McDonald are singularly lacking in any spiritual feeling. It is clear that the Sergeant did not seek either light or shadow to imply religious implications or significance. Instead, the photographs are best seen as imperial images, worked up by a military man with a straightforward mind, recording the terrain of a weakened ally, Turkey, which was allowing Britain to possess and map what would be its future possessions. In an age of empiricism and positivism, photographs could be “matched” to biblical sites and became part of an archaeological collection of evidence that reinforced stories told in the Bible. The intellectual thought process matched the straightforwardness of a McDonald image: if a place mentioned in the Bible can be found, then the existence of this sacred terrain “proves” that the Bible is not only true but also “history.” Charles Darwin was thus challenged on the empirical ground of scientific evidence.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.