AMERICAN STORIES: PAINTINGS OF EVERYDAY LIFE. 1765 – 1915

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

October 12, 2009 – January 24, 2010

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles

February 28, 2010 – May 23, 2010

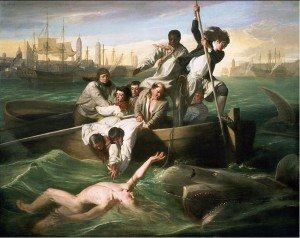

American Stories is a beautiful exhibition, worth every penny of its exorbitant $20 admission fee. One walks into the room at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and is immediately greeted by long-lost friends, usually seen only on the pages of art history books—Paul Revere (1768) and Watson and the Shark (1778) both by John Singleton Copley, Mary Cassatt’s The Cup of Tea (1880- 81)—with the rest of the excellent paintings spread out in, beckoning in rooms beyond. The Paintings of Everyday Life span a remarkable period in American history, the time when we were becoming American. The exhibition tells more than stories, it tells who and what we were. But these works are not history, for the artists interpreting or narrating life as they understood it. The last paintings done for the show were completed one hundred years ago and we view them with the eyes of those who know what we have become.

John Singleton Copley. Watson and the Shark (1778)

The first rooms focus on the transition from the early American painters, one step beyond the charming limners of the past. Clearly these artists lack the rigorous training of their European counterparts. There is no Jacques Louis David in the making. Perhaps because early American artists of the Eighteenth Century could make a living only as portraitists, we meet the Early Americans as specific individuals who are affluent enough to pay to have their aristocratic self-fashioning recorded for the ages. As elegant and as wealthy as they look, our ancestors are also endearing, due to the artists’ somewhat awkward grasp of anatomy. The heads of their subjects are slightly enlarged and seem to rest unsteadily on the well-clad bodies, as in Copley’s Portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Mifflin (1773). Proportions of the body are slightly off but all the details are carefully outlined and proffered as attributes of the successful upwardly mobile and aristocratically inclined upper classes. The wall text explains that the by-play between the married couple of Charles Wilson Peale’s Portrait of Benjamin and Eleanor Ridgely Laming (1788) is delightfully sexual (despite the big heads). Benjamin is holding a long hose-like walking stick that points towards Eleanor who is wearing a virtuously white dress. The phallic stick points to her crotch, and a pile of carefully cradled fruit in her lap reinforces the prediction of future fecundity.

By the next century, such innocent Freudian slips are rare. American artists are better trained and even folksy artists, such as Lily Martin Spencer and George Caleb Bingham, are producing handsome and well-painted works. Winslow Homer and his successors of the Ash Can School can hold their own with European trained artists, William Merritt Chase and Thomas Eakins. But for sheer virtuosity, few can equal the dazzling brushwork of European trained artists, such as Mary Cassatt or John Singer Sargent at the end of the century. But the formal accomplishments of the American artists are less interesting than the story of America recounted in the paintings. The young country was absorbed in defining itself as a new world of new people who are creating a new way of life offered the artists a wide range of stories to tell. The exhibition is centered upon genre paintings and leaves out landscape paintings, unless they contained a narrative. Even though their original social matrix has vanished, these paintings still act out theatrical tales that lend themselves to interpretation. The wall text provided by the museum is fanciful but seems to be possible within the historical context. The reader is not informed whether the statements come from scholarship or from the curator’s reading of the art, but, ultimately, the paintings themselves tell the most interesting stories.

The artists of the nineteenth century were more open minded or more observant of the great variety of Americans compared to today’s contemporary popular culture, which is ubiquitously white and middle class. Perhaps because the artists of the past were literally present at the creation of a new nation, they avidly recorded everything “American,” as “America” came into being. These painters would have been only a generation or two from immigrants, and, indeed, many of the artists were recent arrivals from the Old World themselves. They were white and male, although a few females dared, here and there, to make art. They or their parents were of European origin and the sheer novelty of “America” was still very real. Today, we are more settled into our American identity. We have become very set in our definition(s) of what it means to tell an “American story.” In comparison to today’s selective gazes, focused on niche sites, the painters in American Stories were eclectic collectors of the sights of the American scene. Because American history had yet to be written and the judgment of our collective deeds had yet to be passed, our national sins were recorded with the same openness as our national virtues were depicted.

The uniqueness of America is its diversity. The nation was forged from a disparate group of people, who were locked in a life and death struggles for dominance and survival. From the very beginning, Europeans were driven by their lust for land and wealth. Land had to be seized from the Native Americans at gunpoint. The vast lands the Europeans grabbed were too large for a single family to manage. The colonials needed agricultural workers and the cheapest laborers were those captured in Africa and sold to plantation owners and businessmen. If America was a second Eden, the sins of theft, genocide, and slavery were present from the start. American Paintings records the uneasy and unspoken bargain with God, who, it was hoped, was white. With all apologies, God, we were despoiling Eden in your name. It is important to remember that the audience of the time for these works was white and middle class, upwardly mobile and ambitious. What we see today as revealing of an ideology of racism and imperialism would have been viewed in the nineteenth century as simply “American stories.”

For the first half of the exhibition, slavery was legal in many states in America, and by mid-nineteenth century, only in the South. Legal or not, the second-class, subservient position of African-Americans was taken for granted from the Constitutional founding of the nation to the end of the Civil War in 1865. The marginal role of the blacks in a democracy, founded upon the principle of “all men are created free and equal” appears over and over in the art. The inclusion of African-Americans in what Alfred Boime called “The Art of Exclusion” changes after the Civil War. After 1865, African-Americans are more likely to be shown in all black groups, segregated from whites. Whites are portrayed as the upper class in opulent interiors or as recent immigrants, urban poor, in tenements. Then by the beginning of the twentieth century, questions of race are replaced with issues of immigration and urban life among the lower classes. The exhibition, intentionally or not, traces the inclusion followed by the exclusion, followed by the disappearance of blacks from American painting.

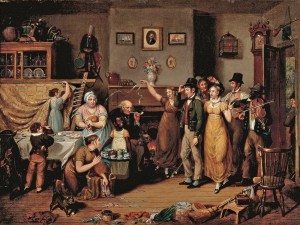

What we see in these paintings are generations of Americans who were aware of what they were doing but were unwilling to confront the meaning and the consequences of their actions. The races live together but the gaze of the white painters is oblique and ambiguous. What are they trying to record? What stories are left behind for us to read? In 1813, John Lewis Drimmel painted the folk work, The Quilting Frolic (1831), which creates a horizontal display of early American life stretched out in infinite detail. Although the catalogue describes the painting as “democratic,” it is, in fact, an examination of an already solidifying class system.

On the left is a family preparing for the party: the quilt is being stretched on its frame and a little boy helps himself to the prepared food before the party begins. Two white servants seem to be caught off guard, in the act of getting ready for the party. A black child, who carries a tray with a blue and white tea service, assists the staff. An elderly white man and his dog, staying warm by the blazing fire, complete the group. On the right, the upper class white guests arrive, well-dressed in spring attire and self-assured in their casual attitudes. They don’t look much like they would be interested in quilting. Indeed most of the arriving guests are top-hatted men and carefree young women. It is unclear whether they are accompanied by or are greeted by a black servant fiddling at the front door. Whoever the guests are, they are obviously of a higher class that the staff depicted on the right.

These two black servants, a little girl and an adult male, are depicted with bulging eyes, gleaming in the whites, and full red lips, parting to display large white teeth. Their African heritage is fully on display: they are the Other, dehumanized and kept carefully in their visual place. The little girl is burdened and fixed in place by her heavy tray. The man is wearing tattered clothes, handed down from a white man. Like all of African Americans, he is musically inclined, or so the whites thought. William Sidney Mount painted a young black man in The Power of Music (1847) who is also entranced by music, reinforcing the white belief that African Americans were “naturally” musical. The man in this painting has features that are far more human and much less a caricature, but he is a mere eavesdropper on the white men who are the ones allowed to make music. A year later, Richard Caton Woodville featured the same marginality of African-Americans in War News from Mexico. The first declared war of American imperialism was waged on another power, Mexico, only recently released from their Spanish colonial masters. African-Americans were excluded from service in this war, but the black man at the far right of the all-white group listens to the reports from the front as avidly as the other men. After all, he is an American, too. Indeed, the rapt little girl, who is standing next to him, wearing the rags of servitude, will live to see the end of slavery.

America was already occupied by a people the Europeans called “Indians,” when the whites arrived. At first there were thoughts of sharing the vast wilderness and the bounty of the new land, but these thoughts were fleeting and soon dissolved into hostile encounters. The First Contact ended in death and disease and by the early nineteenth century, the Native Americans were the Vanishing Americans, living on borrowed time, somewhere west of the Mississippi. Only when whites venture into the West, do they again encounter that other American race, the Native Americans, who once again stand in the way of Manifest Destiny and its remorseless expansion. Racial issues and racial competition are everywhere. George Caleb Bingham, as early as 1845, noted the frequent fact of interracial mixing in his Fur Traders Descending the Missouri. This peaceful scene showed a French fur trader and his son by a Native American woman and their bear cub, gliding impassively along the mirror like river. Once they set foot on land, the boy becomes a “half-breed.” The father and son are more at home on the fringes of the frontier.

For the Native Americans, time is catching up with them. The settlers are on their way, and the 1840s and 1850s are the last decades before the land-hungry whites overwhelmed the native population. It is during these years that George Catlin was painting portraits of a dying civilization, paradoxically at the peak of its glory. The forts he visited were at the edges of the reach of American authority. Here on the frontier, soldiers and warriors of the plains mingled with traders in a brief moment of uneasy peace. But the territory is already a contested one. Charles Deas revels in the violent fantasies of the fight over territory in The Death Struggle (1845) in a painted pulp fiction tale of the Wild West. A trapper and a warrior and their horses plunge over the edge of a cliff to their doom. From our vantage point, we know that both are soon going to be extinct. In a more peaceful vein, Seth Eastman’s Chippewa Indians Playing Checkers (1848) is an indication of how the pastimes of white culture have already impacted leisure time of the “Indians.”

In 1845 William Sidney Mount painted Eel Spearing at Setauket. In 1855 Charles Felix Blauvel painted A German Immigrant Inquiring His Way. Even though we know that Mount had to re-gender the black spear fisherman to a black woman to make the adult less threatening to whites, both paintings show an easy co-existence between Americans of African extraction and white people of European ancestry. “Easy” coexistence does not mean necessarily “equal” in this newly forming country. Ideology informs the brushstrokes which glaze over the conflicting dialectics of democracy and servitude. The subtext of all of the paintings is the assumed superiority of the white race—even children—over the black or red races. The coexistence can continue—-however tenuously—-only if the status quo is unchallenged. The Civil War disrupts the separate existence of the races and upends the previous balance of power. The art made after the Civil War shows the whites living in their world and the blacks living in their world. The interracial interactions seen before the war ceased to be depicted.

Eastman Johnson painted what would be the last of Negro Life in the South in 1859. He provided his curious white audience with a rare glimpse into the private quarters of the slaves on a plantation. It is unlikely that white women would venture into this alien territory, which would have been supervised by the slaves themselves and, possibly, the plantation overseers. But from the growing number of children of mixed race, we understand that white men, probably the master of the plantation and his sons would have been very familiar with the slave quarters. The great secret of these plantations was the unspoken fatherhood of many of the slaves. White women were expected to close their eyes to their husband and son’s mixed race children sired outside marriage. White men were socialized to accept that fact that their children and grandchildren would be consigned to a lifetime of servitude. There are several shades of skin tones in Johnson’s painting: on the left a very light-skinned young woman is being courted by a darker skinned young man. Accompanied by a young black woman, a young white woman enters stage right. We have no idea why she is there. She looks too young to be the mistress of the plantation, but the museum wall text suggested that she is seeking her black kin. It is highly unlikely any white woman would know of much less acknowledge her brothers and sisters of color. We are left to wonder what Johnson was hinting at in his theatrical setting. Thomas Le Clear’s Young America (1863) is a transition work of art, painted during the Civil War, probably in the North. Carefree white youngsters of middle school age are playing outdoors, while a slightly older African-American teenager watches on the fringes.

These paintings draw the lines between the racial groups: the young white girl is sneaking into a place she does not belong; the black teenager is not allowed to play with the white children. Not until the Civil War are the races brought together. According to the catalogue, the artist, Theodor Kaufmann served with the Union army when the war moved into the South. As the federal troops marched from one Confederate capital after another, the slaves ran, literally for their lives, toward freedom and their only protectors, the Union army. The military was overwhelmed by the presence of the runaway slaves, men, who wanted to serve and fight for their country, women and children who had no where else to go. On to Liberty (1867) shows a group of women, dressed in simple working clothes, light weight and light colored dresses, leading their children in the direction of the Union army. When the painting was completed, the war was over, and the South was occupied by the victorious federal troops. But by the time Winslow Homer painted The Cotton Pickers in 1876, Reconstruction was over, the occupying army had withdrawn leaving the former slaves to their fate at the hands of a South determined to regain control over the errant black population.

What is interesting about these two paintings is the lack of whites. The African-Americans are alone. The interaction with whites is over. The women in Homer’s painting could be the women imagined ten years earlier by Kaufmann. They are still in the South, still working on the very land where their ancestors were enslaved. These women are undoubtedly sharecroppers. They have earned the land they work, but they do no own it. Beautiful and unhappy, they appear stoic and calm, standing among the indifferent cotton plants, silhouetted against the sky. Somehow we place this painting as a pendent to Homer’s earlier, The Veteran in a New Field of 1865. The veteran is white and harvests his own wheat crop. The viewer understands that the African-American women are harvesting, not their own fields, but those of their former (and present) master, or someone very much like him. Farming and endless labor is all the women know.

But a few paintings of African-Americans indicate some measure of progress. Sunday Morning by Thomas Hovenden and A Pastoral Visit by Richard Norris Brooke, both of 1881, show quiet domestic scenes among African-American families. These groups are lower class but not destitute. In fact, their living conditions are positively palatial compared to the actual situation of African-Americans at the time. The simple but well-appointed interiors must have been idealized. Photographs taken by Margaret Bourke-White in the 1930s as she traveled throughout the South, recorded that, forty years later, African Americans were living in shacks. The interior walls, without insulation, were covered with newspapers, illustrated by pictures of consumer goods out of the reach of black people. Having formed their own separate culture and social groups, blacks in the paintings of the 1880s appear to accept their lower class situation with contentment. At least they are slaves no longer.

Clearly, a national ideology was at work in the art world of the nineteenth century. What is unclear is the extent to which the artists were critiquing society or whether they were responding to changing social attitudes. The existence of an artist in America was too tenuous to overtly challenge the collectors and audiences without due cause. After the Civil War, people were tired of war and conflict and we can, perhaps it is best read these paintings as attempts to record and reconcile race relations. It would seem that the only way to acknowledge racial differences was to keep the races separate in these documents of color. The only African-American artist shown in this exhibition, Henry Ossawa Tanner, depicts a grandfather giving his grandson The Banjo Lesson. The year was 1899. The century is nearly done. During the early twentieth century, the people of color disappear from art made by white people.

The stories not told are compelling in their absence. We do not see paintings of the continued genocide in the West, the lynchings and the reign of terror in the South, and the grinding poverty of the poor of all races. Artists of the nineteenth century delineated class and racial differences very carefully. What we are seeing in these racially-based paintings is a social arrangement. The first arrangement is slavery and servitude and the second arrangement is segregation and servitude. Both arrangements are strategies of separation of the races. Both arrangements guarantee white power. Neither arrangement was made with the consent of the oppressed group. Under the brushes of the artists, the non-white races are kept frozen in time, trapped in their social place, caught between historical slavery and current subservience, between the noble savage and the marauding savage. People of color were carefully constructed as compliant with their supposed destiny. “They” accepted their supposed inferiority. Meanwhile, Americans who are white evolve and change, migrate and move and improve their status, leaving Americans of color behind in the historical dust of their Gilded Age.

America has always considered itself “white” and “European” and even today there are those who work hard to repel those who also claim the identity “American.” Those to be denied are those who are neither white nor European. But the whiteness of America is but one political ideology. There is another defining belief in what makes “America,” and that is the belief in American inclusiveness. America is a brave new world because it is the first world to welcome all who come to its shores. For some, it is the European cultural heritage of America that guarantees its “exceptionalism;” for others, it is the diversity, the complexity, the changeability, and the inclusion of the nation that constitutes its “exceptionalism.” The American Story told in this exhibition is one of Difference and Otherness, living side by side, but never coming together to form one America. Perhaps that day will come.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.