Eadweard Muybridge and the Horses of Leland Stanford

Part Two

On the sixth of June in the year 2015, a horse won the Triple Crown. After a drought that had lasted almost four decades American Pharaoh galloped to a win by five lengths. The Los Angeles Times celebrated the event with a full color photograph on its front page the next day. It was a classic image, a beautiful horse in full flight, all four hooves tucked perfectly neatly under its belly. In 2015, this image is commonplace and considered classic, in 1872, the prevailing assumption was that when the horse was at a full gallop, the legs would be full rocking horse–stretched out and hovering off the ground.

Jean Louis Théodore Géricault. The Derby at Epsom (1821)

It was the British photographer Eadweard Muybridge who teamed with an American entrepreneur and railroad magnate Leland Stanford to reveal to the world the secret behind the gallop. Muybridge’s photograph, which ended the “rocking horse” gait in an instance, caused consternation on the part of painters, some of whom were forced to redesign their running horses mid-stride. But the photographic technology of the time was very primitive and after a few years, Muybridge and Stanford resumed their joint research on horse racing, and this time they pushed the envelope on film technology so far that they created a new art form–something called awkwardly but accurately “moving pictures.”

Seth Wenig. Associated Press. American Pharaoh Crossing the Finish Line (June 6, 2015)

For this odd couple, Stanford and Muybridge, horse racing was not a hobby, not a pastime, but combined the important business of sport with scientific curiosity. Leland Stanford, like Muybridge, was a remade man who came West to find new opportunities and rose to become governor of the brand new state in 1861. Stanford was not a bad governor and not any more corrupt than was usual in this time, but his pet project was not the state of California itself, but the Central Pacific railroad and his prime contribution to the future of the territory was the use of Chinese labor to build his own fortune, thus enriching the state culturally. The famously taciturn former governor was part of what was known as the Big Four or the four men, including Collis P. Huntington, Mark Hopkins and Charles Crocker, all of whom had partnered in investing in a long shot railroad, called the Central Pacific Railroad, that would run from the gold mines of the state to the east, where it would join with another rail line. The federal government, at the time fighting a war with the Confederacy, needed a railroad that spanned the nation and was willing to subsidize the Big Four. Although the railroad was not completed before the war ended, the entrepreneurs used public funds for their private gains, buying up the land that abutted the railway, and became wealthy thanks to what was eventually named the Southern Pacific Railroad. The four men, Huntington, Crocker, Hopkins and Stanford, were also called “The Octopus,” a dubious tribute to the many armed empires they created, controlling land and transportation and fortunes.

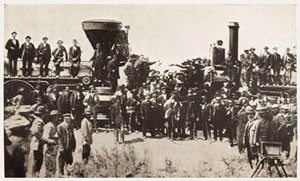

A. J. Russell. The Central Pacific and the Union Pacific meet on May 10, 1869. Promontory Summit, Utah.

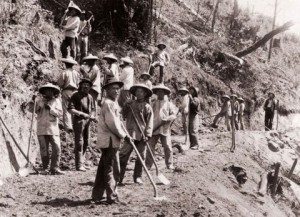

Finding cheap labor was one of the means of gaining a profit from the extended building of the railroad over difficult terrain, and, despite initial misgivings, the Big Four recruited Chinese laborers from Canton to work for wages that were half of the Irish workers. Rather than pay the room and board for the Chinese men, as they did for the Irish, the railroad allowed the Asians to cook their own food and to follow their odd practice of frequent bathing and gave them the most difficult and dangerous jobs, such as blasting through mountains.

Chinese Workers

The extent to which the magnates got rich, thanks to the dangerous and often unacknowledged efforts of the Chinese, can be measured by a small but significant detail: Leland Stanford owned some six or seven hundred horses, depending on the source you read, purchased with his excess wealth. In an elegant twist of irony, it was Stanford (not the Chinese) who was advised by his doctor to find a hobby, after all, the former governor was exhausted after building the Central Pacific. The hobby was harness racing, in which a fast trotter pulled a driver in a wagon, and the Palo Alto Stock Farm became the best in the world. Awash in time and money, Stanford became obsessed with the sport of harness racing and developed a new way of training trotters from colts, not from adult horses, and revolutionized the sport. A keen observer of the progress of his vast hoard of horses and the very precise way in which they were trained to trot, Stanford, naturally, was fascinated with where each leg was at each point in time and with when the hoof struck the ground or not. Even though he watched them train every day, Stanford’s human brain could not keep up with the information his human eyes actually took in and his conscious mind could not register precisely what the horses actually did.

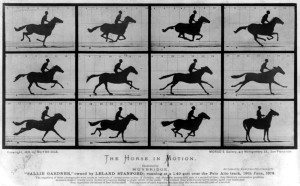

Eadweard Muybridge. The Horse in Motion (1878)

The challenge was to capture the motion of a horse with a non-human instrument, the camera, which was an extension of the human eye and the human brain. From the beginning of photography, the viewers were amazed at the difference between what the mind of the viewer could perceive or could comprehend and what the camera actually captured. The wealth of detail embedded in the paper or in the film is more than the human needs to understand and the human brain is very discerning and selective and seems to have finite speed in taking in what the eyes scan. Stanford turned to Muybridge and his camera and offered to pay his expenses to figure out a way to capture the process of running, horse style. This commission or project was remarkable in that it could provide information that, on the surface, seemed to have the sole purpose of satisfying the curiosity of a group of very wealthy men who had too much time on their hands. The only other group that wanted to solve the riddle of how a horse ran were artists who had long assumed that, if the horse’s hooves ever left the ground, it would have been in what was called the “rocking horse” or “flying horse” position, or with all four legs straightened out and elevated. It seems obvious that the analogy was between humans whose feet left the ground only when jumping or whose foot was always in contact with the ground when running, but a horse is not a human and the question, however minor, was unanswered, until Eadweard Muybridge used the money, some $2000, of Leland Stanford to invest in numerous cameras to photograph a horse over time as it moved across space. What began as an idle bet among the bored elite ending, improbably, in the invention of the first new way of making art for hundreds of years–a novel process named the “movies.” In the meantime, according to Stanford Alumni, Stanford’s Palo Alto System of training horses was so successful that his horses “set 19 consecutive world records and in 1891 held the trotting mile record for each age group”

As discussed in a previous post, Muybridge’s first attempt at capturing a horse’s gallop had been adequate but the trajectory of his studies was interrupted by his trial for murder and his protracted trip to Central America. When he returned to San Francisco, Muybridge resumed his work on instantaneous photography and by discarding the primitive shutter and replacing the one camera with a bank of cameras. As the horse ran the track, wires tripped the cameras and each camera positioned at careful distances, captured an instant of the horse’s progress. Note that Muybridge could move from camera to camera and pull out the resulting images in order. He could then arrange the still pictures in sequence so that the horse’s run could be replicated, moment by moment. According to Nancy Mowll Mathews, Charles Musser, and Marta Braun in Moving Pictures: American Art and Early Film, 1880-1910, Volume 1, by 1879, the photographer had not just perfected the art of capturing motion but he had also fashioned himself as an expert in “zoopraxography” or the new science of animal motion. He shared his findings with the still-fascinated public in a series of cabinet cards, which could be reproduced by the press, and a number of lectures. For the audiences, listening to and witnessing the lantern slides for “The Motion of the Trotting Horse,” the singular poses of the horse in motion were strange and unnatural and even comical compared to the graceful (and fanciful) paintings they were used to. But there was no disputing the validity of his work, “Horse in Motion,” which appeared and was validated in Scientific American in 1878.

Given that Stanford and Muybridge were both based in California, it is no surprise to find a small but interesting snippet in the Sacramento Daily Union on December 28, 1881 in which the photographer showed his research to most famous artist in Paris, Ernest Meissonier (1815-1891):

MEISSONIER AND MUYBRIDGE.

Our Paris letter of December 4th says : – ” A magnificent entertainment took place last week at the residence of Meissonier, where were congregated a large number of 1 the most celebrated scientists, artists and literati of Paris. The object of the prominent artist was to introduce to his friends Mr. Muybridge of California, and to afford them an opportunity of witnessing a very remarkable exhibition, for it is generally known in our Golden State that this gentleman has made wonderful discoveries in photographing the movements of hursts and other animals while in motion. The exhibition consisted of pictures or rather a large number of photographs projected with the aid of the oxyhydrogen light, the size of life, upon a screen, illustrating the attitudes assumed by a horse during each 12 inches of progress while performing the various movements of hauling, walking, ambling, cantering, galloping, trotting, leaping, etc., many of these positions being foreshortened and exhibited as seen from various points of view. In many of these pictures the successive actions of the muscular system were plainly distinguishable. With the aid of an instrument called the zoopraxi. scope, many of the subjects were exhibited in actual motion, and the shadow traversed the screen, apparently to the eye as though the living animal itself were moving ; and the various positions of the horse and the dog, many of which when viewed singly are singular in the extreme, were at once resolved into the graceful, undulating movements we are accustomed to associate with the action of those animals. Other pictures illustrated the actions of the dog, the ox, the deer, etc.; besides the attitudes of men in the act of wrestling, jumping, running and other athletic exercises. The most remarkable and beautiful pictures were probably those of birds on the wing, whose movements were plainly visible, although the duration of the exposure of the negative was only the one-five-thousandth part of a second. The greatest applause followed the exhibition of each, and the many artists, whose greatest works on canvas or marble are those of the human figure, warmly congratulated Mr. Muybridge on the wonderful discovery which is destined to render such valuable aid to science and the arts.”

It was no accident that Muybridge and Meissonier were together in Paris–Meissonier and Stanford had worked together in 1881 when the famous artist painted a portrait of the famed California. And as Edward Ball pointed out in The Inventor and the Tycoon: A Gilded Age Murder and the Birth of Moving Pictures (2013), in this small portrait Stanford chose to pose with a copy of Muybridge’s album of horses in motion. When Muybridge himself arrived in Paris, he was greeted like an intellectual rock star, introduced to the French public as an inventive scientist by his admirer, the French photographer, Étienne Marey (1830-1904), who took the American research even further. Dissatisfied with the multiple cameras of Muybridge, in 1882, Marey updated the design for the photographic gun that Muybridge had sent and improved the invention, so that it could take twelve exposures a second. That same year, Marey invented something, while inspired by Muybridge, was entirely new: a chronophotographic fixed plate camera, a camera that had a distinctive advance–a timed shutter. And years later it was Marey who would first use a strip of “film” in 1888 to carry his sequential images. However, it was Marey and Meissonier, both of whom fêted Muybridge in Paris, who unwittingly built the fame of the photographer to the point where it eclipsed that of Stanford. It was only natural for a Parisian audience to follow the lead of the famous scientist and the famous artist and admire the amazing zoopraxiscope (Greek for “animal action viewer”) and its quick succession of images that passed by so quickly that they seemed to be “moving.” To this day, it is possible to actually turn the circle of images created by Muybridge into a “movie.”

The Zoopraxiscope and the disc of sequential pictures

During 1881, the year when both Muybridge and Stanford were in Paris, something happened between the two men. In 1882, when The Horse in Motion was published in San Francisco, Stanford, who wrote the preface, credited a “J. D. B. Stillman” and mentioned the name of Muybridge only once. Given that Muybridge’s photographs of horses at the gallop had been published years earlier and the public was well aware of his contribution, this omission made it clear to the photographer that his relationship with his sponsor and patron was over.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.