Nineteenth Century Imperialism in the Middle East

Part Two: Félix Bonfils and the Levant

The Levant was essentially a European imaginary configuration imposed upon a certain stretch of the moribund Ottoman Empire, but more precisely, the Levant, a term derived from the French word for “rising,” or “levant,”meaning “to rise,” like the sun or “to get out of bed in the morning.” For French kings, the “Levant” was a ceremonial event, witnessed by privileged courtiers, and the importation of a French word to an Arab speaking word speaks volumes of the rising Orientalism during the nineteenth century. During the early decades of the century, the lingua franca of the coastal region east of the Mediterranean Sea, was a simple version of Italian, but when the ties of the French government and the Ottoman Empire strengthened, in the second half of the century, French became the European language of the Levant. On one hand, the Levant was, since the fifteenth century, a figment of European desires, on the other, its major port cities, such as Beirut and Alexandria, signified the commercial role of the region as a conduit for European trade. As a map of the area suggests, the Levant was border territory, a slice of land where East and West met, where Jews, Christians and Muslims mingled, and where empires, British, French and Turkish sat down to do business.

As the outward looking edge facing Europe, the Levant was comparatively familiar, while the interior of the territories east of the trade coast were virtually untouched by either the French or the British, the key players in the Orient. But as the French were in the midst of building the Suez Canal, in 1861 the Emperor Napoléon III became uneasy over the unknown deserts stretching beyond his control and knowledge. The blank map, today’s Saudi Arabia, was a truly dangerous place for the unwary and un-pious to visit, for here was the home land of the most virulently fundamental strain of Islam, the site of the Wahabee beliefs. The individual selected by the Emperor to reconnoiter this interior–in disguise–was one of history’s strangest characters, William Gifford Palgrave (1826-1888). Although he came from a privileged sector of British society, Palsgrave was one of those restless Europeans who fled the conventional and banked like a pool ball around a variety of identities and guises. He began as a Protestant, became a Jesuit, and, as a scholar of all things Arabic, Palgrave was as close as any European could come to being an expert on Muslim society and religious beliefs. In his 2003 book In Pursuit of Arabia, Rāshid Shāz attempted to untangle the complexities that were Palgrave.

“It is difficult to believe how Palsgrave, who came from a respectable British family the members of which excelled in the service of Britain, could come to identify himself with France, a rival Empire..The only way to reconcile theses two apparently contradictory identities was to assume the role of a European imperialist rather than that of a British or a French one. This enabled him to see the world divided into two blocs, European and non-European,” Shāz explained.

Like all Europeans, especially missionaries, such as Palgrave, this spy for the Emperor believed firmly in European superiority. The result of his journey, the purpose of which was to examine and diagnose the extent to which these “savage” and “ignorant” people could be elevated or saved, was a polyglot volume, The Personal Narrative of a Year’s journey Through Central and Easter Arabia (1865). The Narrative mixed facts, especially ethnographic descriptions of heretofore unknown tribal peoples, with the European assumptions and fantasies about them, a combination that did not please exacting scholars of the “Orient,” but, during the decades when France and England were sharing the power in the Levant between them, delighted the more causal readers, eager for narratives of imperialism.

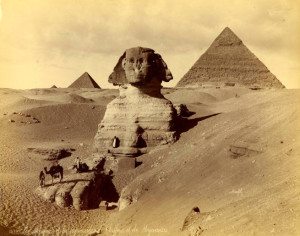

Félix Bonfils. The Sphinx (1870s)

But Palgrave deserves our attention today, for he was literally the first European to enter into the capital of what Shāz termed “the Wahabee Empire,” Riyadh. This “empire” was an internal one, tucked inside the Ottoman Empire, but, because of power of its unique religious beliefs, the region could resist and indeed lead a revolution against European interests. Unfortunately, Palgrave conflated a fringe view of Islam with the broader Muslim faith, and, given that only Saudi Arabia is still the heart of Wahabeeism, this confusion still exists today. Still, his writings on the Wahabees, the first of their kind in the 1860s, echo eerily today: he writes of how this branch of the faith was spread though “the sword” and forced marriages, similar to the tactics ISIL uses in the twenty-first century. The adventures of Palgrave in the lands of Saudi Arabia, the interior beyond the civilized lands of the Levant, blazed a trail for T. E. Lawrence to follow during the Great War, when, bringing the predictions of Napoléon III to fruition, he allied the British with the Wahabee regime against the Turks. In contrast to the dark and unenlightened interior space of fanaticism, the coastal “Orient” was a place of tourism, rapidly being modernized by the presence of railroads and, of course, the Suez Canal, which opened in 1871.

It is important to make the distinction between the myth of imperialism and the actual extent of the literal power of those Europeans, who would dominate in the Middle East, and the limits of the territorial power of the Turks, the British and the French, can be measured by the careful incursion of W. G. Palgrave into the land of Wahabeeism and danger. Indeed, it can be argued that “Orientalism” can be geographically located in the Levant, a crossroads of global influences, where the European control both begins and ends. Here, it is easy to “imagine” the “mysterious east,” in the process of being mapped and measured and occupied both mentally and physically by Europeans in such a way to make it safe and preserve its “mystery.” During the significant event of opening the Canal in which ancient Egypt was dragged into the modern world and placed beneath the imperialism of European rule, a remarkable family of French photographers, headed by Félix Bonfils (1831-1886) were carefully photographing the entire architecture and archaeology of the region. Setting up in Beirut in the Maison Bonfils, the activities of Bonfils extended to Jerusalem and Egypt and even to Greece, all under the nominal control of the Ottoman Empire while being confusingly but peacefully “occupied” economically by the British and the French. This all-encompassing generational project by a single family paralleled the consolation of European power in the Middle East and established a visual and pictorial terrain of scenic vistas that constructed the collective European imagination of possession and empire.

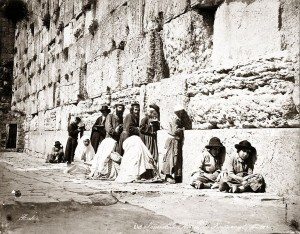

Félix Bonfils. Jews at the Western Wall. Jerusalem (1870s)

At a time when intrepid Europeans were roaming over the Middle East, collecting souvenirs of various sizes–works of art, mummies, and in the case of the Germans, entire temples, photographs became a more acceptable way of removing historical artifacts from their place of origin. Félix Bonfils, who had studied photography under the nephew of Nicéphore Niépce, Niépce de St Victor, had worked in Arles, until his son Adrien developed respiratory ailments. Bonfils had served with the French military in Lebanon and remembered its dry climate, excellent for those with breathing problems. The entire family moved to Beirut and all became involved in the serious business of photographing the Levant and Egypt, resulting in what is claimed to be 15,000 images, including some 8,000 stereographs. Upon the death of his father in 1885, the son took up the business, assisted by his mother, Lydia. Adrien, in fact, seems to have move on by 1900, but Lydia, who had been in charge of making the albumen for the wet plates, remained so active that she had to be removed from Lebanon in 1917 when the Great War finally arrived to put the coup de grâce to the Ottoman Empire.

The interests of the family mirrored the imperialist mindset of the French and English: an interest in mapping through images, creating an inventory of historical sites, and a careful record of an ancient past, often related to the Bible, that was under threat of modernization as the Ottoman influence waned and the Europeans pressed their claims on what they considered to be their historic (Christian) inheritance and the cradles of their civilization. In the 2011 exhibition In Search of Biblical Lands: From Jerusalem to Jordan in Nineteenth-century Photography at the Getty Museum, curators noted that “Military and economic aims merged with religious fervor and the advent of archaeology” and photography played an important part in the imperialism of the period. Maison Bonfils was engaged in a frankly commercial enterprise, aimed at tourists and at those who traveled via photographs. Today, we “possess” as individuals, obsessively “taking” images wherever we go. In the nineteenth century, this kind of inventory was the domaine of professional photographers, such as Félix Bonfils. He knew his audience, religious pilgrims who sought the authentic Bible, adventurers tired of the familiar and hungry for the novel, and the entire panoply of military and government staffs who occupied the Levant. The audience at home, back in Paris or London or New York, wanted information, places to attach to names, and, while the work of Bonfils did not function as “evidence,” his photographs were straightforward documents.

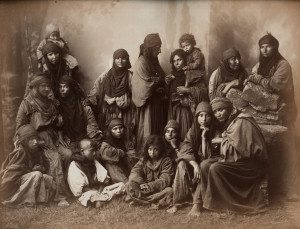

Félix Bonfils. Bedouin Women. Jerusalem (18780s)

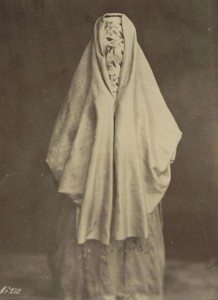

Maison Bonfils could be counted on to print thousands of excellent, detailed, well-composed, informative images of the Levant, a territory that was multi-cultural and international. The mental position or the psychological attitude of the point of view of the Bonfils camera, whether single image or stereograph, was one of and imperial gaze that reflected the colonial posture of France and other European nations. The prevailing mindset of the Europeans during the nineteenth century was nicely summed up in 1903 by Hermann Vollrat Hilprecht, Immanuel Benzinger, Fritz Hommel in Explorations in Bible Lands During the 19th Century. They write about “Restlessly shifting nomads in the north and ignorant swamp dwellers in the south have become the legitimate heirs of Asshur and Babel. What a contrast between ancient civilization and modern degeneration!” Driven by vanity and unexamined assumptions of superiority, the Europeans overlooked the present and sought the glories of the past to be retold in their own terms. The Bonfils family not only participated in this antiquarian mindset of acquisition but also joined in the contemporary practice of making encyclopedias of “types” of people. This early form of classification of population groups was greatly enhanced by photography which allowed for a higher level of surveillance, and the massive collection of Bonfils family photography included “types” of Semitic peoples found throughout the Levant.

Many of these photographs of the inhabitants of the region were made, not for the individuals photographed, but for a consumer base of Europeans who needed souvenirs and reassurance of the exoticism of the Other. Often posed artificially in the Bonfils studio, with oddly un-Oriental backdrops, the peoples of the Levant seem frozen in time, retaining their quaint folkways, while all around them, the European “civilization” teems with industry and purpose. There are haunting photographs of women in all enveloping burkas, while other women display their faces and gaze straight at the camera. It is possible to assume that it was Lydia who photographed the women of the region. This vast archive of the Middle East was distributed, along with the array of vistas, views, and sites of the “Orient,” in Paris, London, and even in America. The ambitions of the Bonfils family and its business sense can be seen in the translations of the labels which were published in three languages, English. French, and German. Few of the original glass negatives have survived and most of what has come down from Bonfils are the prints themselves. The most significant volume was, oddly enough, produced by Bonfils after he returned to France in 1878, Souvenirs d’Orient, which won a medal in Paris on the occasion of the Exposition universelle of the same year.

Very little has been written on Félix Bonfils, although there is an excellent catalogue dating from 1980, Remembrances of the Near East: The Photographs of Bonfils, 1867-1907, presented by the Jewish Museum in New York. This seminal and to this day definitive exhibition was prepared by Robert Sobieszek who used the term “Romantic Orient” to describe the cultural construction of the Levant. The term is an appropriate one, for it evokes the “romanticism” of Eugène Delacroix and Jean-Léon Gérôme, painters who recreated what was an alien culture into visual terms the French people could comprehend. Sobieszek referred to the work of Bonfils as

“picaresque” since they are images of travel and souvenirs of distant locales meant to instruct and entertain. They are “picturesque” in that they depict the exotic as well as the natural in order to pictorially delight.” The curator also points out the formal and compositional correctness used by Bonfils to “create the prolixity of the Oriental dream..Bonfils’s work is a veritable photographic chrestomathy, like those selected Arabic texts complied earlier in the century and designed to teach the language, except here it is the visual language of the look of the Orient.”

The brief catalogue, which consisted of about two paragraphs, concluded with a list of the publications of the family Bonfils: Architecture antique: Egypte, Grèce, Asie Mineure. Album de photographies (1872), Catalogue des Vues photographiques de l’Orient (1876) and Souvenirs d’orient. Album picturesque des sites, villas et ruined les plus remarquables de l’Egypt et de la Nubie (de la Palestine, de la Syrie et de la Grèce) (1878). Although all the photographs were signed “Bonfils,” it must be assumed that many images were taken by family members.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.