Percy Wyndham Lewis (1882–1957)

Wyndham Lewis was born on a yacht named “Wanda,” attended the famous Rugby School in England and was educated as an artist at the Slade School in London. He began well but he ended badly, labeled a fascist, who scuttled back to his home country of Canada to wait out the war in relative comfort. Lewis was more of a writer than an artist but his early art works, inspired by the ideas of the Vortex and propelled by the Great War, were worthy of note. In many ways, the career of Lewis was typical of several of the English Vorticist artists–the time for the movement was far too short for a complete development–with his exploration of the ramifications of this British Cubist-Futurist hybrid were truncated. The paintings Lewis did before the War were far more interesting that those during the war and infinitely more experimental and consequential than after the War. For art historians, Lewis is a minor figure, factored in only when he is studied within the larger movement of Vorticism.

Wyndham Lewis. Portrait of the Artist as the Painter Raphael (1921)

Lewis, a wealthy British educated colonial, was part of that generation raised by the Slade professor, Henry Tonks (1862-1937). Before the War, Tonks was a mainstream artist but, during the conflict, he became an artist of great note. But the surprising turn of the career of Tonks was in the future, and when Lewis arrived in 1899, his classmates included fellow Canadian David Bomberg, Mark Gertler, William Roberts, and Carrington, who would kill herself when the man she adored, Lytton Strachey died of cancer in 1932. Roberts and Bomberg would distinguish themselves as war painters, but at beginning of the century, when they all graduated from Slade, they were the new generation of British artists. At the beginning of the twentieth century, London was not exactly an art center, and in 1902 when Lewis was expelled from Slade for laziness and insolence, he headed for Paris, where the action was.

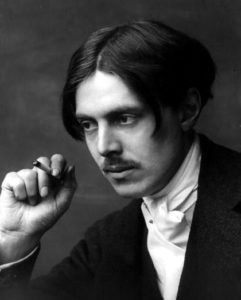

George Charles Beresford. Wyndham Lewis (1913)

Although accounting for Lewis’s years in Paris is not easy, his first novel, Tarr, published as a book in 1918 is perhaps a fictionalized account of his formative years. The first appearance of “Frederick Tarr” was in 1914 and his various adventure were serialized in 1915 and 1916, as if the story was still in progress. In his 1993 book, Ezra Pound, Wyndham Lewis and Racial Modernism, Vincent Sherry suggests that the protagonist, “Frederick Tarr,” is a thinly disguised Lewis, hanging about the expatriate communities and lingering as hanger-on around the circle of Gertrude Stein. His private wealth allowed Lewis the luxury of extending his education in a causal manner that enabled him to pick up echoes of intellectual conversations taking place around the leading thinkers of the time, Henri Bergson, Georges Sorel and Rémy de Gourmont.

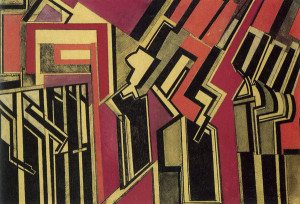

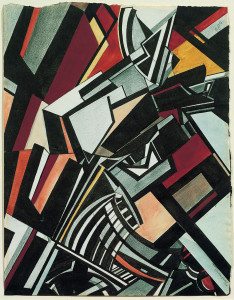

Wyndham Lewis. Red Duet (1914)

Due to dwindling funds from his wealthy family, Lewis returned to London in 1909, full of ideas and for the rest of his life he would return to this artistic well. However, he would later write in 1939,

I would like, at the risk of appearing a little nationalist, to deprecate the artistic ascendancy of Paris in the Anglo-Saxon world. If English painters–and American too–are to go back to nature, to English nature and American nature, they need bother very little about Paris. Paris has its function; but it is that of an art school, nothing more. A finishing school, let us call it. I myself am Paris finished.

Most accounts of Lewis’s life assume that simply because he was in Paris he must have absorbed Cubism, but Cubism had not yet started when he returned to London on that first occasion. The origins of Lewis’s painting style is frustratingly vague, and it is difficult to account for his jump into abstraction, a leap that neither the Cubist or Futurist artists made. And yet, upon his return to London, Lewis simultaneously began his career as a writer and resumed his association with his friends from Slade at the Omega Workshop. It seems clear that Lewis was not in sympathy with the aims and philosophy of the decorative arts workshop for he left after a dispute with Roger Fry in 1913. Many of the early works done in this period are lost, destroyed or painted over, but he exhibited with what passed for being “advanced” in London, perhaps realizing in the process that there was leadership vacuum. Roger Fry and Walter Sickert were tied to post-Impressionism and the arrival of the Futurists at the Sackville Gallery in 1912 was a warning that the art world had moved on past the older generation.

Wyndham Lewis. Plan of War (1914) presumed lost

The rupture with Roger Fry had an dividing effect on the small but growing numbers of London artists interested in the latest Parisian art, represented in an exhibition curated by artist Spencer Gore (1878-1914). Gore had worked closely with Walter Sickert and Lucien Pissarro (1863-1944) and was well acquainted with the work of Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), having visited the Gauguin retrospective at the Salon d’Automne in 1906. Gore was a great organizer and joiner, being part of the Camden Town Group, the Fitzroy Street Group, and, according to the Tate Museum helped set up the Allied Artists Association. Clearly Gore was positioned to bring together a number of factions within London, and as Helena Bonett of the Tate relates,

Displaying his often noted powers of diplomacy, in 1913 Gore brought together the fractured artistic groupings for an Exhibition of the Work of English Post-Impressionists, Cubists and Others at the Brighton Public Art Galleries from December 1913 to January 1914. The Camden Town and Fitzroy Street groups occupied the first two rooms, and the ‘Cubists’ – including Lewis, Epstein, David Bomberg, Frederick Etchells, Edward Wadsworth and C.R.W. Nevinson – the third. Gore had even tried to include the Bloomsbury Group, but Fry wrote to him that it was too soon ‘after so violent a rupture’ with Lewis over a disputed commission.

In the paragraph, Bonett mentions that less than a year before the War, Lewis and his Slade friends are, a year after the Futurist exhibit, already part of the “cubist” group which made up yet another “Group,” this one founded by Lewis and called the Rebel Artists Centre, financed for three months by his lover, Kate Lechmere. The Rebels were yet another masculine group that so characterized the beginnings of Modernism: exclusionary and hostile to women. As Christopher Nevinson said when the Centre was formed, “Let’s not have any of those damned women.” The Centre was perilously close to the Omega Workshop, being a cross between a design atelier, a school where one could receive “art instruction,” and a salon where the notorious Futurist leader, Filippo Marinetti, came to perform. However, Lewis was suspicious of Futurism and of the efforts of Marinetti to incorporate the English artists into his fold and disrupted one of Marinetti’s evenings at the Sackville Gallery. By 1914, it appears that due to his exposure of Cubism and Futurism, Lewis had, in his characteristically inclusive fashion, absorbed what he needed and rejected what he felt was alien to England and formed his own version of modern art. “Modern art,” he said, “has nothing to do with ‘the People.'” The public, which in its peaceable state was the undifferentiated “crowd,” could easily degenerate in to a mindless mob. In contrast to the changeable and fickle crowd, art itself stood to all that was fundamental and eternal.

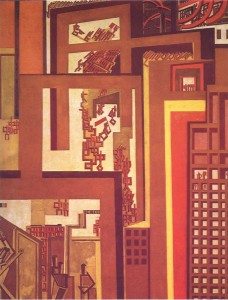

Wyndham Lewis. Workshop (1914-1915)

One of two surviving oil Vorticist paintings by Lewis

The impact of Futurism in London was much greater than it could ever hope to be in Paris, where Italian art was originally rejected by Cubist advocates. In fact Christopher Nevinson and Marinetti prepared a British manifesto for an English Futurism, entitled “Vital English Art.” As Michael J. K. Walsh, in his 2005 article, “Vital English art: futurism and the vortex of London 1910-14,” pointed out the publication of the manifesto in the Observer precipitated a split in the London avant-garde community. Neither Nevinson nor Lewis trusted Marinetti, who was prone to taking the lead, to allow the English artists to play roles other than as followers. But Nevinson had close ties with the Futurists, especially Gino Severini, who he had known in Paris, and was more amenable to accepting the guidance of Marinetti. The Manifesto, published in June 1 1914, however, was in Marinetti’s voice: “I am an Italian Futurist poet, and a passionate admirer of England. I wish however, to cure English Art of that most grave of all maladies-passe-ism. I have the right to speak plainly and without compromise, and together with my friend Nevinson, an English Futurist painter, to give the signal for battle.”

Wyndham Lewis. The Crowd (1915)

Exhibited at the Second London Group Exhibition in 1915, also known as Revolution and Democratic Composition

One can see how Lewis could object to such a declaration from Marinetti and Nevinson. While he certain agreed with Marinetti that English art needed to be radicalized, he felt that only the British artists could understand the modern and the industrial, not to mention the force of the “crowd,” a feature of London: people pressing in on all sides. In fact, the other avant-garde artists whose names were fixed to the manifesto were equally irritated and they signed a letter dissociating themselves from Marinetti and Futurism. The final act on the rebellion the English artists against the Italian interloper took place at the Dore Gallery site of an eight work exhibition of Futurist art. According to Walsh, Nevinson attempted to give an address and was attacked by the other modern artists in London,

Lewis and the artists whose names had been used in the manifesto, with Hulme and Gaudier-Brzeska in addition, heckled Nevinson, let off fireworks and generally disrupted the evening. Nevinson particularly recalled the heckling by Gaudier-Brzeska and Jacob Epstein, which acted only as a prelude to violence that finally erupted when Marinetti attacked Gaudier-Brzeska, and Nevinson lunged for Ezra Pound. The London avant-garde was now fatally and irreparably split.

Nevinson became the leading English Futurist, while Lewis became the leader of a counter movement, Vorticism. Using racist language, Lewis declared, “you wops insist too much on the machine. You are always on about these driving belts, you are always exploding about internal combustion. We’ve had machines here in England for donkey’s years. They’re no novelty to us,” thus asserting the British primacy in the industrial revolution.

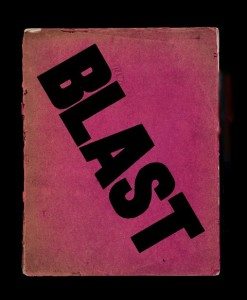

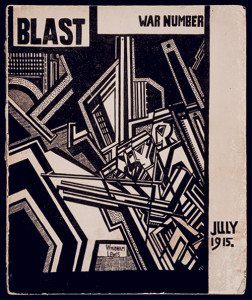

Working with the poet Ezra Pound, Lewis, already developing into an excellent writer in his own right, stated the publication BLAST, the literary counterpart to Vorticism. As with all boutique periodicals, this artist run journal was short lived, only two issues: one came out just before the Great War and the last BLAST was published in 1915. BLAST was a polemical manifesto, loud and noisy and damning of all things British. The writers, inspired by Futurist typography and by Marinetti’s use of words to assault the senses, blasted its few readers with staccato declarations. However, Lewis had a serious purpose in his work. Like the young modernists of his time, he realized that art, whether literary or visual, had to participate in the modern itself, from industrialization to urbanization to the mechanization that was running the world. He considered, correctly, that Futurism, Cubism and Expressionism, coming from Italy, France and Germany, could not fully express the “new conditions and possibilities.” As Carolyn Tilghman’s 2007 article on “Lewis in Contention: Identity Anxiety and the London Vortex” put it, Lewis considered that modern life belonged “to England alone.” She wrote,

Insofar as it moves away from the natural, the sentimental, and the embodied (and) towards the efficient,the aggressive and the mechanical, modernity is the product of England more than any other country. And modernity demands an aesthetic that is not intellectual or humane but ruthless, an aesthetic that arises form hard, barren ground in celebration of the life of the machine, raw energy and discord.

Wyndham Lewis. Composition (1913)

Apparently Lewis was stressing the point that while England had lagged behind in the arts, it had surged in industrialization which had made the nation the most modern in Europe. If this was the case, then it stood to reason that the French were mired in tradition, the Italians who came from a rural country, and the Germans, absorbed in their own inner romantic life were incapable of expressing modernity. On the other hand, it was also clear to Lewis and his contemporaries that they were caught up in the vortex of modernity, a whirlpool of change that Edwardian England nostalgically resisted. Through BLAST and its strikingly maroon pink cover, the spokesmen for Vorticism attempted to condemn formalist art, especially the well-bred theories of the Bloomsbury set, such as the “significant form” of Clive Bell’s Art (1914), which had just been published. But it was necessary to challenge the Cubists and the Futurists on their own ground and Lewis devised his own aesthetic for a modern age: geometric, i.e. unnatural, and representational, abstract in appearance but not abstract.

The paintings by Lewis that have survived were striking and powerful, tending towards graphic design, devoid of the organic and inattentive to the human. in her essay in for the MoMA exhibition, Inventing Abstraction, Leah Dickerman noted that although there were Vorticist artists who admired Kandinsky, whose work appeared in BLAST, Lewis tended to think less in terms of art’s trend towards abstraction and more in terms of “abstraction as an outgrowth of the conditions of modern life, life qualified by industrialization and concentrated power, though not reduced to the Futurist thrill of speed.” Lewis’s paintings from the brief years of Vorticism should be considered in terms of engineering. Like the Russian Avant-Garde artists a years later, Lewis felt that in this modern word, artists and engineers were coextensive. His lines were ruled and sharp and one can discern impersonal forms that are not abstract but the mechanical abstraction required to design machines–the mechanical objects that increasingly determine the shape of the world. The artist defies the engineer’s blueprint with offsetting bold irrational colors that infuse the inanimate with the frisson of life. Only Crowd has an discernible imagery and the rest of his paintings, such as they survive, imply a labyrinthine map for a crazed contraption that is severely rational and radicalized. More akin to Orphism than Cubism, these paintings were as cutting edged and as original as anything that was being produced in Paris just before the Great War broke out. But the works by Lewis lack to formalist methodologies of Picasso and Braque and the exuberance of the Delaunays: there is a darkness around the edges, indicating his understanding of the machine and all its prophetic powers.

Vorticism was a brief artistic phenomenon cut short by the Great War which scattered artists all over Europe. Lewis fought for his adopted country in France and emerged from the conflict a changed man. His art was never as radical again, reverting to the kind of awkward Cubism of Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger as practiced before the War. Although he continued to paint, Lewis became better known as a writer than as an artist, and correctly so. Sadly, one of the “Men of 1914” along with Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot, Lewis went down in infamy as one of the English fascists who initially extolled the achievements of Adolf Hitler. His misplaced faith in fascism backfired when the Germans went to war against England and Lewis and his wife were able to escape to the comfort of Canada, thanks to his place of birth, on a yacht named “Wanda.”

Wyndham Lewis. A Battery Shelled (1919)

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.