Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (1889-1946)

The Artist as a Futurist, Part One

Although it may sound counter-intuitive, outside of Italy, it was on the soil of England that Futurism found most fertile. After being attacked by Umberto Boccioni in the catalogue for the Futurist exhibition at the Bernheim-Jeune Galerie in 1912, the French artists may have eventually shown a sneaking interest in Futurism; but, for the most part, it was only patriotic to reject the Italian renegades. In the end, as appealing as the dynamic visual language of Futurism might have been to the Parisian artists, the paintings shown at Bernheim-Jeune were viewed through the prism of “derivative” of Cubism. Clearly, Paris, as the capital of the art world, and Cubism as the leader of the avant-garde in Europe, had the territory of leadership to guard. But in England, the terrain was quite different. Volumes of art history have tended to overlook or give short shrift to British art, comparing it unfavorably to the preferred the Modernist art coming out of the studios of starving artists in Paris. But, that said, from Whistler to Tissot, London had long been a thriving community of interesting and thoughtful artists. In addition, the largest city in the world was also the home of the art critic who had written, long before the French, multiple books on contemporary art, John Ruskin (1891-1900), author of Modern Painters (1843–60). The problem in London in the year 1910 was two-fold: the art scene there was considered a backwater and its days of glory appeared to be long past.

And yet, it was in London that the rambunctious leader of the Futurist movement, Filippo Tomasso Marinetti (1876-1944) built an audience of interested young artists. He published his Futurist Manifesto (1909) in a small British publication, Tramp, in 1910, and arrived in London that same year to shake his British audience out of its self-satisfied lethargy. One of Marinetti’s main lines of attack was on British art itself through the esteemed John Ruskin. The art critic had died ten years earlier and, it must be said, that it had been some years since he had been in possession of all of his faculties. But he had been, in his own way, a trailblazer, crafting a discourse for modern art and contemporary culture, as viewed from the vantage point of social moralism. In his own time, Ruskin was considered by his contemporaries to be not just a man of his own times but also a man of the future, deeply impacted by a nascent movement in Marxist thought. As Russian writer, Leo Tolstoy, remarked, “One of those rare men who think with their hearts, and so he thought and said not only what he himself had seen and felt, but what everyone will think and say in future.” Marinetti disagreed. The Victorian critic was now in the twentieth century a man of the past and stood for everything that was old and outmoded. Nevinson biographer, Michael J. K. Walsh noted that Marinetti had spoken, in French, at the Lyceum Club, demanding “radical change and to catalyze the final demise of an outdated and reactionary order in London.” The title for the wide-ranging lecture (or harangue) was primly titled, “Lecture to the English on Futurism.”

C.R.W. Nevinson. Bursting Shell (1915)

Even though Roger Fry had just opened the seminal exhibition, “Manet and the Post-Impressionists” in November, a mere month before Marinetti’s talk to “the English,” the full import of the show was still being absorbed. For the English artists, the double blows of Fry’s definition of “modern art” and Marinetti’s attack on the past would have sounded like a wake up call–for those who were listening. In retrospect, as Walsh noted, Sir Herbert Reed said that “The modern period in British art may be said to date from the year 1910.” If Marinetti was part of the jolting of the artists in London from the past to the present, he confronted his audience with all its inherent intelligence as being bound and gagged by the past and stymied by ancestor worship. The man, called “the caffeine of Europe,” chided the listeners for their “sluggish ideology of that deplorable man, Ruskin..his morbid dream..his nostalgia..his hatred of machines, of steam and electricity..his infancy.” In hindsight, one could read this passage as perhaps the attack of a proto-Fascist upon a photo-Marxist, but at the time, Marinetti, arriving in the wake of Fry’s “post-Impressionists,” was reminding the British that, although they had led the Industrial Revolution, art had moved forward without them.

Present at the Marinetti presentation at the Club was Margaret Nevinson (1858-1932), mother of the future Futurist artist Christopher Nevinson. As Ellen Ross relates in her 2007 book Slum Travelers: Ladies and London Poverty, 1860-1920, Nevinson was a devout Christian and ardent feminist and early suffragette, a proverbial “daughter of a clergyman,” married, unhappily, to a man who was flagrantly unfaithful to her. Despite his obvious faults, such as complaining about how his wife contradicted him, Henry Nevinson (1856-1941), a journalist, was also a feminist. Margaret Nevinson worked for the poor of East London and taught young women, while writing for the betterment of the lower classes and fighting for the improvement of the legal and economic lives of women. Her artistic son, Christopher, would grow up to be a conscientious objector when the world war that Marinetti had called for in 1910 finally came to pass in the summer of 1914. Therefore it is most ironic that his sixty year old father, Henry, served and was wounded at Gallipoli. Most sources on Nevinson discuss his work as a Futurist, nominally connected to the Vorticist movement, and focus on his work as an artist during the Great War, but “Richard,” as he was known in his immediate family, was also the son of distinguished and prolific writers, who espoused social and political causes considered very advanced, even futuristic, for time. Angela V. John wrote extensively about a rather caustic family environment in “A Family at War: The Nevinson Family.” John quoted the elder Nevinson writing sadly that his son would not be, like himself, an intellectual or a journalist or a social revolutionary: “No, my son absolutely refuses to go to Oxford. He cares for nothing in the world but ‘art.’ It is a dreary prospect.” It should be pointed out that the father’s lament was uttered a year before Marinetti came to town.

In researching the back history of Christopher Nevinson (as he was known as an artist), it becomes apparent that the English artists who made the leap into the future, whether as Futurists or as Vorticists, came from singularly troubled and disaffected backgrounds: most of the men were in states of dislocation. Among them, only the well-to-do Edward Wadsworth, comes across as stable. Although he too came from a privileged family, Nevinson was an unhappy child, at odds with his older sister, who was a musician, often in conflict with his perpetually dissatisfied father. He cleaved, it seemed, to his encouraging and supportive mother, but he was a manic-depressive and prone to fits of rage, especially after the Great War. In his biography, written in the 1930s, Nevinson was still trying to work out his various resentments when he wrote, “If my mother does happen to be in for a meal she is so engrossed in other things that she hardly hears and certainly never takes in a word I say.”

One might speculate that Nevinson became a Futurist to defy his proper parents but that conclusion would be incorrect. In fact, his parents, especially his father, were adventurers. His father, a war correspondent when he was not a suffragette, had been in Bulgaria during the First Balkan War of 1912, stationed in the same town as Marinetti who would later write Zang Tumb Tumb (1914). In fact, Henry Nevinson, a veteran of the Boer War, even wrote on performance art, a Futurist invention, in the years before the Great War. And as Walsh pointed out in his article of Margaret Nevinson, she attended the lecture of the Futurist leader in order to review the ideas of this man who had dim views on women. According to Walsh in his 2005 article in Apollo on the relationship of the Nevinsons and Marinetti, Margaret Nevinson wrote of the Italian agitator in The Vote: “The members of the society are young men in revolt at the worship of the past. They are determined to destroy it, and erect upon its ashes the Temple of the future. War seems to be the chief tenet in the gospel of Futurism: war upon the classical in art, literature, music” So Nevinson’s parents knew Marinetti before the young artist even made his acquaintance.

The complications and compromises continued, as Nevinson’s father, who so objected to his chosen vocation, spend decades supporting and nurturing his artistic career, albeit behind the scenes. There seems to have been a contest between father and son over who was best known, and, as times changes and fortunes fluctuated, the honor was passed back and forth between the pair. During the Great War, as Nevinson acquired a reputation as an outspoken truth-teller of the real conditions of the battlefields, in direct contrast to the more censored accounts delivered by British journalists, such as his father. According to John, for years, the two were open and public rivals during their long an uncomfortable relationship. She also revealed in her article that Nevinson’s loyalty to Marinetti apparently extended to an exhibited sympathy for British Fascism during the 1930s. Today, it is the artist of war, Christopher Nevinson, who is the best-known, possibly because, as John wrote, “Richard Nevinson cultivated that seemingly modern construction, the celebrity. His apparent determination to behave badly and alienation of significant art critics came to camouflage his real achievements as an artist.”

Nevinson began his mature engagement with art at the famous Slade School of Art, which produced the famous generation of young British artist, educated before the War and schooled by the War. Although Nevinson was anxious to escape the horrors of English public school, where his father had consigned him, he was wary of Slade. In Paint and Prejudice (1937), he described his sufferings: “I went to a large school, a ghastly place from which I was rapidly removed as I had some sort of breakdown owing to being publicly flogged, at the age of seven, for giving away some stamps which I believed to be my own. I was not only described as a thief but as a fence. From this moment I developed a shyness which later on became almost a disease. During my sufferings under injustice a conflict was born in me, and my secret life began.” Given the dislocations within his family–his parents lived apart–his conflicts with his father and sister, and given the years of problems in school, it is understandable that the young Nevinson was shy and lacking in social skills when he arrived at Slade. But art schools are forgiving of the outsiders and, soon, he found himself part of a gang or group who called themselves the “Costers.” The Costermongers were street vendors who wore a distinctive small black hat and sold fruits and vegetables from a cart.

The idea that the son of Margaret Nevinson, a reporter for London’s East End and a champion for the lower classes would appropriate such a “costume” for fun is a measure of the distance of the son from the ideas of the parents. The Gang included Mark Gentler, Stanley Spencer, John Currie, Edward Wadsworth, and the young men were later joined by Dora Carrington, the femme fatale of Slade. Both Nevinson and another student, Paul Nash, who would also become a famous war artist, fell in love with Carrington. But she had eyes only for the intellectual Lytton Stratchey (1880-1932), a gay man who was emotionally unavailable to her. Mark Gentler, Nevinson’s best friend, also loved Carrington and asked her to marry him. In fact Nevinson’s biographer Michael J.K. Walsh noted the futility of the non-affair with the beguiling and elusive artist, referring to “her notorious desire to remain unattached.” Nevinson had already suffered one romantic loss while he was attending a predatory school for artists, St. John’s Wood School of Art. He recalled, “My shyness went, and I spent a good deal of my time with Philippa Preston, a lovely creature who was later to marry Maurice Elvey. There were others, blondes and brunettes. There were wild dances, student rags as they were called… and various excursions with exquisite students, young girls and earnest boys; shouting too much, laughing too often.” Suddenly, as though weary of the onslaught of male attentions, Carrington broke things off with Nevinson and with Gentler who then ended his friendship with Nevinson. One reads these soap operas of the Slade set and the Bloomsbury group and recalls Nevinson’s difficulties with his equally elusive mother.

Nevinson’s exit from Slade might have also been participated by Henry Tonks (1862-1939), the famous teacher who presided over this unruly group of students. One of the males–Tonks thought it was Nevinson–impregnated a young female model, and the compassionate Tonks started a fund for the mother and child, a fund to which Nevinson refused to contribute. Tonks, at some point thereafter, announced to the wayward pupil, now bereft of the woman he loved and without his best friend, that he would never be an artist and had no further future at Slade. It was perhaps a shock to Tonks when, two years later, four of his pupils, Wadsworth, Nevinson, Spencer, and Nash, and himself, all became artists of the Great War. But whatever the psycho-dramas of the entangled group of teenagers, it seems clear why Nevinson left Slade and travelled to Paris where he completed his studies at the Académie Julian and Matisse’s Cercle Russe.

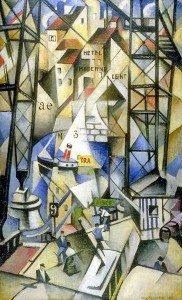

C.R.W. Nevinson. The Old Port (1913)

Nevinson ran in fast and promising company during that brief year (1912-1913) in Paris where he shared an atelier with Modigliani. At some point during that year he also met his parents’ “acquaintance,” Marinetti, through the Parisian-based Futurist Gino Severini (1883-1966). Severini was at the Futurist exhibition at the Sackville Gallery in 1912 when he met the young Nevinson. According to Walsh, the definitive guide to the Nevinson family, in his 2007 article in Apollo, Serverini dined at the Nevinson household and explained Futurism in French to the English family. At some point the Italian artist introduced young Nevinson to Marinetti through a letter: “I have to tell you about a young painter whose name is Nevinson. I met him during my exhibition, and he introduced me to other young artists, who, with him, all became convinced futurists … Nevinson will thus introduce himself to you on my behalf.”

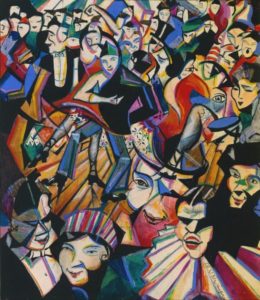

Christopher Nevinson. Dance Hall Scene (1913)

Once in Paris, Nevinson seems to have quickly assimilated both Cubism and Futurism and quickly created his own style, which combined both vocabularies of the Salon Cubists and the vivid colors and mobile forms and the fragmentation that was the slicing of Futurist lines of force. These pre-war paintings were surprisingly upbeat and pleasant, lacking the heritage of Cézanne that haunted the Salon Cubists and the political drive that pressed against the Futurists. At this stage of his career, Nevinson’s Cubo-Futurism is a young man’s assessment of two very serious styles, superficial and attractive, but, compared to his English counterparts, light years ahead. His departure from Slade had made it possible for him to sprint ahead of Spencer and Nash and allow him to use the slashing diagonals of Futurism less than expressions of the rushing restlessness of modern life and more as statements of the pity of war. When Nevinson returned to London, the world was on the edge of the Great War.

The Arrival (1913)

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.