Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (1889-1946)

The Young Futurist Goes to War

1914-1915

In 2011 English art historian, James Fox, the very cute successor for Michael Wood, discussed Christopher Nevinson in his British Masters series. He explained that Nevinson was “lured” to a London theater where he watched Filippo Tomasso Marinetti perform one of his experimental sound poems, evoking war. Although the audience, Fox tells us, was divided in its reactions, Nevinson was fascinated. It is hard to believe that Nevinson had to be “lured,” unless one understands that Marinetti was a friend of his father’s and knows that the son and the father were rivals for their entire lives. Fox does not give a date for the meeting in the account, but we know that Italian Futurist Gino Severini made an introduction for the young artist to the infamous agitator and master provocateur so that the two could meet in Paris in 1913. Marinetti was frequently in London, giving performances and holding Futurist evenings, well attended by the young artists of London. By the time Nevinson returned from Paris to London, he was steeped in the languages of Cubism and Futurism. True, as Fox pointed out, his understanding of these complex movements was facile–gained during a mere year of observation–but he was able to put his own interpretation on the paintings of this period. In 1913, Nevinson was perhaps the most advanced avant-garde artist in England.

Christopher Nevinson. Self-Portrait (1911)

Closely allied with the Futurist movement, Nevinson appeared in that exhibition that was an awkward marriage between Post-Impressionism and Futurism at the Doré Gallery. Here, Nevinson was reunited with classmates from the Slade Art School, such as Edward Wadsworth, who suddenly became known, with some exaggeration, the “Cubo-Futurist school.” Frank Rutter, the English supporter of avant-garde art, declared Nevinson to be the author of “the first English Futurist picture.” Suddenly, a young man, disaffected from his family, asked to leave Slade, was the center of attention in London. He now had enough élan to join a group of dissident artists, called the “Rebels,” led by Wyndham Lewis. The Rebels included William Roberts and Frederick Etchells, future Vorticist artists. The small group met with the famous Marinetti at a dinner in his honor in November of 1913. According to Michael J. K. Walsh in his 2007 article for the Apollo magazine, the artists were concerned over Marinetti’s determination to control everything in the name of Futurism, but Nevinson was unconcerned. He and Marinetti actually performed together at the Doré Gallery in April of 1914. The conferenza, as it was called, took place on the occasion of a massive Futurist show of eighty paintings and sculptures, featuring all the leading Futurist artists. The works of art served as backdrops to the readings by Marinetti of his sound poems and the earnest discussions by Nevinson of his newly honed theories on avant-garde art.

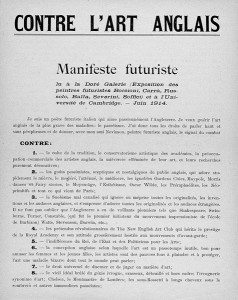

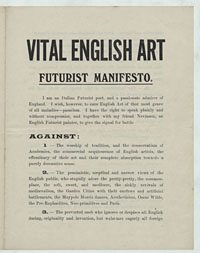

Marinetti asked Nevinson to produce simulated cannon fire on command and later described the performance as something that would have seemed familiar to those who witnessed Joseph Beuys at work decades later: “Blackboards had been set up in three parts of the hall, to which in succession I either ran or walked, to sketch rapidly an analogy with chalk. My listeners as they turned to follow me in all my evolutions, participated, their entire bodies inflamed with emotion, in the violent effects of the battle described by my ‘words-in-freedom.’ ” By the late twentieth century, performance art would be considered one of the important innovations of the avant-garde, and it is possible today to understand the significance of these Futurist evenings in London, where, unlike in Paris, Marinetti could receive a warm welcome. And Christopher Nevinson, even though he still spoke in the voice of Severini, was at the center of an important new tendency in modern art. But the possibilities of developing the nascent Futurism of London were, like time, rapidly running out. In June of 1914, Nevinson had attained the status of “Futurist artist,” to the extent that he issued a joint manifesto with Marinetti himself, “A Futurist Manifesto: Vital English Art,” often called “Vital English Art” for short. Published in the The Observer on the 7th of June 1914, the manifesto was supposedly signed by his colleagues, including Canadian artist, David Bomberg. Marinetti with his typical bombast declared that he (and Nevinson) wanted “to cure English Art of that most grave of all maladies-paste-ism.”

However, having their names attached to a document by Marinetti was an affront to the desire of the Rebel artists to establish themselves, not as an English outpost of Italian Futurism, but as a group of artists uniquely British and uniquely modern within the English context. Quickly the now-disaffected group published a reply in The New Weekly, expressing their anger at having their names used without their knowledge or permission. The result was a breach, during the last summer before the War, between Nevinson and his colleagues. The angry Rebel Art Centre now acted as a group and, in true Futurist style, disrupted a lecture Nevinson was giving at the Doré gallery. The breach was complete. Once again, Nevinson had to go his own way. He now had two major sets of enemies: the Bloomsbury group that surrounded Roger Fry and the Rebels who would become Vorticists. Although Lewis and the other Vorticist artists would eventually repudiate both Futurism and Cubism, both he and Pound would appropriate Marinetti’s confrontational technique of stringing together strident declarative sentences in their own magazine, BLAST. In a particularly nasty and racist invective rant against Marinetti, Lewis asserted that “you wops insist too much on the machine. You are always on about these driving belts, you are always exploding about internal combustion. We’ve had machines here in England for donkey’s years. They’re no novelty to us.”

It is difficult to determine the extent to which the English audiences were aware of or understood the extent of Marinetti’s utter devotion to the cause of Italian national assertion against the Austrians. Obsessed with the Libyan War of 1911, he lectured constantly on the dangers posed by Austrians to audiences throughout Europe and his famed sound poems, composed on the occasion of the war in the Balkans in 1912, were couched in his concern for the future of Italy in the Dardanelles. Given that he lectured in French, it is possible that the English artists were more interested in Futurist art than in Marinetti’s imperialism. When the Great War began at the end of July 1914, Italy declared, to Marinetti’s fury, neutrality. On the surface, given that Italy was an ally of Austria and Germany, this neutrality should have been the preferred position for the poet. According to Ernest Ialongo in his 2015 book, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti: The Artist and His Politics, Marinetti, “Italy had little public support to fight on their behalf or to engage in the war at all. For Marinetti, this was unacceptable. Italy, he felt should be on the side of France against the scourge of German/Austrian passatismo, and to conquer irredentist land. Milan was a hotbed of interventionist activity. Violent public demonstrations between pro and anti-war demonstrators had already begun by August 1.”

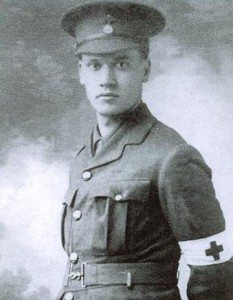

While Marinetti and his Futurist associates, such as Carlo Carrà, were busily attempting to turn Italian opinion towards intervening in the War, Nevinson and his former colleagues considered how best to approach the War, as soldiers or as artists, or both. By now Nevinson the younger was twenty-five and suddenly adrift: his English colleagues of the Rebel Art Center had rejected him and his Futurist friends had retuned to Italy. In the waning days of summer of 1914, Nevinson, who had experienced warfare only at his former school, Uppington, signed up for the Friends’ Ambulance Unit organized by the Young Friends or the Quakers. For the British, it had been a long time since they had last fought a war on the Continent and the experience of the Crimean War suggested that an ambulance service would be necessary. The Friends organized very quickly, only days after war war declared on August 4th, and began training volunteers in September. The Quakers immediately established themselves in Dunkirk on the coast and near the battle lines in France. Despite his youth, Nevinson was unfit for active fighting and the Quaker unit was immediately available to a conscientious objector, allowing him to do his patriotic duty and to shift his life into another phase.

Nevinson in his Red Cross Uniform

The common view of the Great War is one of trench warfare and insane frontal charges resulting in the loss of the youthful flower of an entire generation. This image is correct but only after the opening months of the War. Until the winter of 1914, the war was mobile, with the Germans pushing through Belgium and into France, pausing at Marne, Eiffel Tower within binocular sight. As the Germans gored Belgium and stabbed towards Paris, these were the months when the vast majority of the causalities and deaths occurred. As Alan Kramer wrote in his 2008 book, Dynamic of Destruction: Culture and Mass Killing in the First World War (Making of the Modern World),

The enormous losses in August and September 1914 were never equalled at any other time, not even by Verdun:..the total number of French casualties (killed, wounded, and missing) was 329,000. At the height of Verdun, the three-month period February to April 1916, French casualties were 111,000. In fact, the three months April–June 1915, which included the failed Artois offensive, with 143,000 casualties, and the months June to August 1918, the checking of the massive final German onslaught and the victorious counter-offensive, with 157,000 casualties, were both bloodier than the height of the battle of Verdun, but still did not match the blood-letting of 1914. In general, French losses were higher than those of the Germans and the British, because French defensive positions and trenches were less efficient..Taking just one part of the casualty figures, the numbers killed, as reported by the medical service, confirm that the first three months of the war were by far the deadliest, with death rates of 1.43 per cent in August, 1.65 in September, and 1.04 per cent in October 1914. Such high rates were never again to be reached..Contrary to received wisdom, it was not trench warfare, but the mobile warfare of the first three months which was most destructive of lives. The death rate of September 1914 was at least ten times higher than those of December 1915, January 1916, and January-March 1917, and forty times higher than those of January and February 1918.

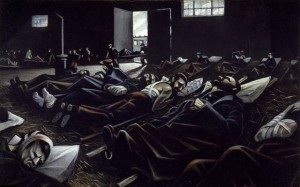

The Friends worked in evacuation sheds of Dunkirk, saving lives and sending the broken and dying men to the hospital ships, which would ferry them to England. This was the hell into which Christopher Nevinson stepped. Any notion that war was “glorious” or that this event was a Futurist dream come true was brutally extinguished. As the artist recalled, ““When a month had passed I felt I had been born in a nightmare. I had seen sights so revolting that man seldom conceives them in his mind and there was no shrinking seen among the more sensitive of us. We could only help, and ignore shrieks, pus, gangrene, and the disemboweled.” It was here in these railway sheds, called The Shambles, that Christopher Nevinson, known as “Richard” by his family, worked alongside his father, Henry, the war correspondent. In her 2006 book, War, Journalism and the Shaping of the Twentieth Century: The Life and Times of Henry W. Nevinson, Angela V. John related the story of Henry Nevinson, who, in addition to his work in the Ambulance corps, in the face of censorship, reported, as best he could, on the campaigns in France. The Quaker ambulance unit was headed by Philip Noel-Baker, who would become a Labour leader after the War, and he oversaw the rescue of the crew of a torpedoed cruiser in the Channel and then supervised at Dunkirk, where the volunteers found thousands of French and Belgium soldiers–later to be joined by wounded German prisoners with “suppurating, stinking and gangrened wounds.”

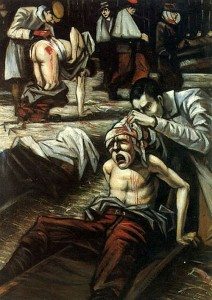

The Doctor (1916)

When the Allied doctors refused to treat these prisoners, the Quakers, including the Nevinsons, took care of them. It was the job of the younger Nevinson to attend to the dying men. As he recounted later, “Our doctors took charge, and in five minutes I was nurse, water-carrier, stretcher-bearer, driver, and interpreter. Gradually the shed was cleansed, disinfected and made habitable, and by working all night we managed to dress most of the patients’ wounds.” These months would be among the last of the father-son rivalry. Having reconstructed himself from “Richard” to “C.R.W.,” the young Nevinson was still in the position of being rescued and supported by his father who would sponsor him to the “official” British artists, such as Moorhead Bone. But the war experiences, in The Shambles and later in Ypres as an ambulance driver, would reshape the art of Nevinson, whose paintings would parallel his father’s merciless recountings in print of a nightmare war. In 1915, after rising to chief medical orderly, Christopher Nevinson returned home, for health reasons.

The narrator the the British Masters series, James Fox, stated that Nevinson was in the front lines only briefly, but he served with the Friends of two and half months, the worst months of the entire War: the months that nearly wiped out the French Army and the months that nearly destroyed the British Expeditionary Force. The disastrous fall was followed by a winter typhoid epidemic and Nevinson returned to London, ill and exhausted. Fox was also skeptical that he presented himself as a war hero, appearing in public in full uniform, walking with a cane. In fact, Nevinson had been weakened by rheumatic fever before the War and had walked with a limp ever since. For the British public, those who served, in whatever capacity, were heroes. Fox also said that Nevinson never served in the trenches, but during his first months of service in the Ambulance Corps, the trench system had not yet been set up. And in his later years of being a member of the Royal Army Medical Corps, the artist would have a great deal of experience with trenches but ambulance drivers drove trucks and being in a trench was not his job.

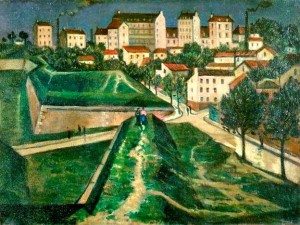

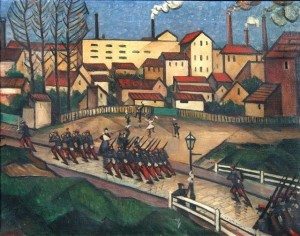

From our experiences with “battle shock,” as it was called later in the War, it is possible to speculate that Nevinson might have been suffering from PTSD and needed a rest, but what we do understand is that his military service, working with soldiers of all nationalities, seeing them at their best and at their lowest, utterly changed his art. He had produced a few paintings of military maneuverings and fortifications when he was in Paris in 1913. Like his confetti strewn painting of the same year, Tum-Tiddly-Um-Tum-Pom-Pom, also known as Dance Hall Scene, these bird’s eye views of the French soldiers were examples of a semi-Futurist artist learning by imitation.

Paris Fortifications (1913)

In comparison to the paintings he did on his return, it is clear that Nevinson had made an astonishing artistic leap from being an apprentice to being the master translator: C. R. W. Nevinson had taken Cubism, laced it with Futurism, and transformed a hybrid language into a visual vocabulary uniquely suited to recording the events of a thoroughly modern and completely nihilistic war where the main goal was mutual annihilation.

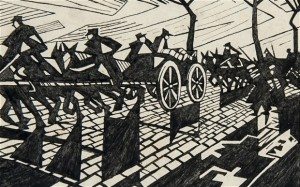

On the Road to Ypres, printed in 1916, thought lost and rediscovered in 2012

Bravo! (1913)

On the Way to the Trenches (published in the second issue of BLAST 1915)

As Nevinson explained, “Our Futurist technique is the only possible medium to express the crudeness, violence, and brutality of the emotions seen and felt on the present battlefields of Europe.” In speaking of his painting about sacrifices of the French soldiers, “La Patrie, he said, I regard this picture, quite apart from how it is painted, as expressing an absolutely NEW outlook on the so-called ‘sacrifice’ of war. It is the last word on the ‘horror of war’ for the generations to come.” More than any other artist of the pre-War avant-garde generation, Nevinson paved the way for the acceptance of modern art, which in his hands suggested that only a modern visual vocabulary was suited for the depiction of a modern war. In the next and final post on Nevinson, the two styles developed by this artist to express and explain this War will be discussed.

La Patrie (1916)

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.