Artists at War

Hide and Seek and Camouflage

One of the odd aspects of the Great War is the surprising fact that it was during these four years that the British artists not only met the challenge of depicting a new kind of war but they also left behind a unique legacy which took a Cubist-Futurist based visual vocabulary and transformed it onto a language for conflict. It is only with the British and Italian artists that the avant-garde goes to war in 1914 and each group took up a specific area of battle. The Futurists, with their fascination with machines, especially those that flew, specialized in airplanes. The British, trapped in trench warfare and bogged down in mud and corpses, showed the horrors of the ground war to a home audience, hungry for information. These two bodies of work from the British and Italian Futurists have been largely overlooked by traditional art history because art historians tend to not take British art seriously and because these bodies of work fall into what is considered a specialized area–“art of war.” The Italian contribution to the translation of aerial warfare into avant-garde art has long been buried under the weight of their pitiless Fascism. Only slowly are these Italian bodies of art being resurrected, now that enough time has past to distance the art from the taint of the glorification of war.

But the British art of the Great War bear no such stain. Instead the art produced by the English painters was a patriotic endeavor undertaken by artists who went to the battlefield, often not as soldiers but as support staff, nurses and medics to the fighting soldiers. The contribution of Edward Wadsworth (1889-1949) was a case in point. In 1915, a year into the War, Wadsworth, very fascinated with the machine, created an imaginary machine. In “inventing” a machine, the artist takes a typically Vorticist approach to mechanization–an artist does not copy machinery or, as one sees in the Cubist-based art of Fernand Léger, refer to it–an artist becomes an engineer and makes machines. The fact that an artist invented mechanical device might have no purpose is simply beside the point, Wadsworth was drawing a picture, if you will, of the new world that echoes the famous statement “mechanization takes command” by Sigfried Giedion (1888–1968) and now commands the battlefields of that narrow arc transcribing the front lines in Belgium and France. It was this mythic Vorticist machine that had transformed conflict in ways that have rendered all historical forms of battle obsolete.

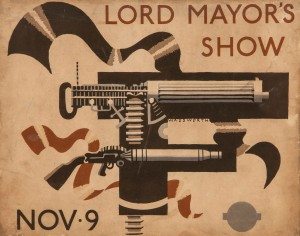

According to Derweatts Bloomsbury Auctions, This 1936 lithograph was known for its controversial modernist depiction of a Vickers and Lewis Machine Gun from the Great War. Wadsworth’s offering for the 1936 poster campaign for the Lord Mayor’s Show caused public uproar as it was pasted on the London Transport network and was subsequently withdrawn from circulation after just 24 hours. Tainted by a climate of pre-war anxiety the British public took aversion to what they believed to be Wadsworth’s glorification of the weapons of war. Responding to these claims in the pages of the Daily Express the artist proclaimed, ‘If people object to this poster… they must object to the Lord Mayor’s Show. Better cancel the whole thing.’

One of the new machines that surfaced during the Great War was the submarine, perfected to a deadly threat by the German navy. The U-boat or Unterseeboot, “under sea boat” was at least two hundred fourteen feet long and carried of crew of over thirty. Hovering off the English coast and patrolling the Mediterranean, the role of the German submarine was to isolate Great Britain and cut off supplies, from food to munitions, vital to the war effort and to control shipping lanes to France. Like the newly formed air forces, the Royal Air Force or the Luftstreitkräfte, there were commanders in the submarine forces who proved to be all to adept at sinking Allied ships. The “ace” of the German submarine fleet was an officer who had French ancestry, Kapitänleutnant Lothar von Arnold de la Perière, whose prowess at sinking or damaging ships was astonishing. Commanding the U-35, he retired with a record of 195 ships sunk (455,869 tons) and 8 ships damaged (34,312 tons) and died in an air crash at Le Bourget airport in 1941.

Although this class of U-31 high sea submarines carried only six torpedoes, Arnold de la Perière usually deployed his deck gun to dispatch his prey and remains to this day the most successful submarine commander of all time, having the lion’s share of Imperial sinkings. The entire German count for all of their submarine fleet was 230, and this extraordinary record of destruction can be explained by the novelty of this new weapon and by the lack of radar which, in the Second World War, could detect the under water vessel. As John Abbatiello, an military expert on anti-submarine warfare, pointed out, “Submarines had poor visibility, lying low on the water, but enjoyed the advantages of stealth, and escaping counterattack by diving.” For a slow and heavy laden cargo ship or a lumbering destroyer, there were few recourses to a foe lying concealed and in wait, but the Allies were able to combine into convoys which allowed the assembled ships to turn on an attacker. By the end of the Great War, the British also used airplanes to attack the submarines which had to surface in order to kill. In the end, the score was almost even, with the German submarine fleet losing one hundred seventy eight boats.

Willy Stöwer. Sinking of the Linda Blanche out of Liverpool (1915)

For the first time, thanks to this scourge of submarine warfare, so expertly practiced by the Germans, it was necessary to conceal the unconcealable–large ships–through camouflage. Although the art of concealment was known in the animal kingdom, humans used camouflage in hunting with the idea of blending in with the natural environment. But the idea of camouflage in warfare was relatively new. On land, massed regiments simply marched towards each other and fired their weapons, which created clouds of concealing smoke. Until the mid nineteenth century, the loading of guns was a slow and laborious process and the soldier was limited to one shot at time. The early guns were difficult to aim and were less than accurate. On the sea, ships towered above the waves with billowing sails and guns mounted below the high decks. As on land, it was necessary to see the enemy in order to fight the enemy. The notion of “skirmishing,” developed by the British army early in the nineteenth century, in which riflemen in green uniforms harassed the front lines of the enemy. During the Peninsula Wars, Wellington proved to be a master at this new form of deployment against Napoléon’s occupying army, considered not only novel but also comical at the time. But skirmishing itself was a form of camouflage itself: the skirmishers were a body of snipers sent to attack the front lines of the enemy, disrupting the steady forward marching of the massed regiments. So effective could these offenses be that although the skirmishers lay in wait and fired from concealed positions, they could be mistaken for the main body, confusing the enemy.

Indeed, fifteen years before Wellington’s green clad infantry were sniping at the French in Spain, Captain Charles Hamilton-Smith conducted an experiment for the Royal Engineers and stated,

Under general circumstances; and in battles, when the distance, the smoke of cannon and musketry, partially, at least, concealed contending armies from each other, glaring uniforms may not have caused serious bloodshed; but in the later wars, and the mode of engaging introduced during the French Revolution, where the rifle service is greatly increased, and clouds of skirmishing light Infantry cover the front of their forces so far in advance as to be checked only by similar combatants pushed forward by the opposing army, the fire of both parties is commonly guided by individual aim, and good marksmen make considerable havoc. The colour of the uniform becomes therefore a question of importance, particularly where it is of so distinct a nature as to offer a clear object to the marksman.

Hamilton-Smith’s experiment was a clear warning that colorful uniforms could not withstand a modern war and his research indicated that the proper color for the modern military uniform was gray. It was take fifty years before the British army could be dislodged from its stylish preference for red, and it was in India in 1848 that the military began to use official uniforms that suited the climate and the terrain. These uniforms were not gray, as recommended by Hamilton-Smith in 1800, but a new color, “khaki,” meaning “dust,” derived from the mazari palm. Stationed in India in 1846, Sir Henry Lumsden, realized the bright white pants and hot red felt coat of the standard British uniform were simply unsuitable to India and he started with his own loose fitting pajamas which he dyed with mazari, an innovation that led to the khaki uniform, approved by the colonial army in India. The regiments who were not provided appropriate clothing took things into their own hands and devised their own uniforms from light weight cloth stained with tea. However obtained, these new colors and new outfits were instantly recognized as serviceable as camouflage out in the “land of dust” that was India. The exact sequence of the adaptation of the khaki color by the British military is a matter of some discussion, and it should be noted that these “khakis” were mostly home-brewed affairs until 1884 Spinners Co. Ltd. of Manchester developed a reliable dye for the uniforms.

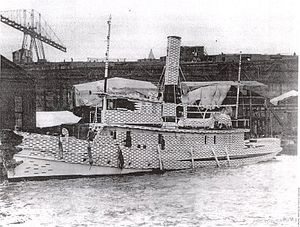

And now one hundred years later, the unanswerable submarine warfare had to be answered by any means possible. There were precedents for camouflaged ships: in the age of cannons, some ships draped painted canvases over the ports to conceal how well-armed they were and two hundred years later, the USS Narkeeta covered itself with brickwork to confuse the enemy. One of the problems with large ships is that they were, in contrast to a motionless animal in nature or a stilled sharpshooter in war, moving, positioned between sky and sea, a dual background that was both static and in motion. The constantly changing weather at sea was another factor: how to conceal within a range from fog to to storm to rain to full sunlight? The other issue is that, unlike a large gun emplacement, which was immobile, the mind of the observer had to be confused in an entirely different way. In other words, one could visually and mentally construct continuity with between a motionless dappled covering and its surroundings, but the challenge with ships was to confuse the enemy, not with concealment, but with the disruption of aim. The precision of the guns had to be confused. Recall that the ace German submarine commander, who was probably responsible for the need to develop a special camouflage for ships at sea, destroyed ships more often with surface guns that with torpedoes.

USS Narkeeta

As with static camouflage, the artists were deployed to create special effects. It is a measure to the difficulty the problem of camouflaging ships that it was not until 1917, three years into the war, that an effective method was finally developed by a marine artist Norman Wilkinson (1878-1971. Wilkinson, a rather bad artist of seascapes, largely derived from Turner, was serving in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve on a minesweeping vessel. The artist had served in Gallipoli and so he was an experienced soldier interested in serving his country. In sharp contrast to the French artists, only some of whom served in active combat, even older English artists joined up. One of these indefatigable mature soldiers was Solomon Joseph Solomon (1860-1927), an Anglo-Jewish painter, not to be confused with the Pre-Raphaelite artist, a famous gay artist, Simeon Solomon who had been charged with sex crimes in 1873 and died alcoholic and destitute in 1905. Like Wilkinson, Solomon was not the greatest of artists but he had game, and the English portraitist became an “R.A.” and depicted King George V, the Queen Mary and Edward the Duke of Windsor in the famous Coronation Luncheon group portrait of 1911.

The fact that he was fashionable and important and portly did not prevent Solomon from joining, as a private soldier, a volunteer corps for home defense, The United Arts Rifles or “The Unshrinkables,” according to Nicholas Rankin author of A Genius for Deception: How Cunning Helped the British Win Two World Wars, a 2008 book that briefly discussed Solomon. The home guard drilled in Piccadilly, near the Royal Academy, and somehow in the fertile brain of Solomon an idea based upon nature came to his head: camouflage. In 1915, he advertised his skills as an artist to The Times in 1915, under the title, “Uniform and color”–“A knowledge of light and shade and its effect on the landscape is a necessary aid to the imagination of a designer of the uniform in particular, and the appearances of war in general.” His suggestions for military uniforms were both based on previous British experiments with khaki and added some advice on “warships. The North Sea is almost invariably a pearly green, and experiments with models should evolve something more subtle than their metallic hue.”

Solomon had spent some time screening trenches with dyed and tinted sheets of muslin to shield trenches from the cameras of aircraft flying above. In these opening years of the War, airplanes were largely used to photograph trenches and almost a half million aerial photographs were developed for the Allies alone. The idea of camouflaging trenches was a good one, but it was also highly impractical, given the constant barraging of the lines and the impossibility of hiding hundreds of miles of emplacements–and four lines of trenches at that–that stretched from the English Channel to Switzerland. Interestingly, although Hamilton-Smith’s report was one hundred years old and khaki was over fifty years old, according to Rankin, the word “camouflage” was not included in the Encyclopedia Brittanica before the War.

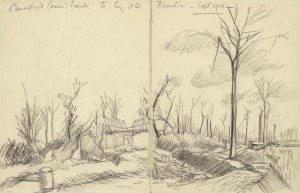

Camouflaged Communication Trench to Company HQ, Picantina: panoramic sketch of communication trenches and a bomb damaged building amongst bare tree stumps just behind the front line. A barrel stands in the left foreground (September 1916)

But in 1920 camouflage expert Solomon,who had already written The Practice of Oil Painting and Drawing in 1911, published another and very different book, Strategic Camouflage. In a section devoted to camouflaging buildings which concealed trenches and other strategic points, he wrote advice to an artist,

Or you can make a lean-to against the south side of a roof, and cover up the whole yard without any but an expert being the wiser, if you use a little skill. But you must be careful that the airman does not take an oblique view of your camouflage, if other houses in the same line or parallel are left to expose their whitewashed sides, windows, and doors, to mark the contrast with what you have shut off from view by your lean-to. In every case it is not wise to interfere with the rigid outline of your roof at the eaves.

It should be noted that Solomon’s approach to concealment in that he is thinking in terms of trompe l’oeil is purely academic and based upon his studies of reproducing nature in art. While the French artists were inspired by avant-garde art, particularly Cubism as Picasso famously claimed, the English artists came to the fine art of concealment and confusion by more circuitous routes. The extremely difficult of hiding a huge ship slowly ploughing the waves of the changeable sea was solved by Norman Wilkinson, two years after Solomon was spreading his muslim tarpaulins over trenches. The next post will discuss the joint operation between Wilkinson and Edward Wadsworth.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.