John Nash (1893-1977)

Dispatches from the Trenches

The famous English artist and painter of the Great War, Paul Nash, had a brother named John Northcote Nash (1893-1977), who was also an artist. Although Nash the younger was also an official artist of the Great War, he was greatly overshadowed by his more famous brother, who was part of the famous Slade School of Art group that produced an entire generation of British artists from one group of students. John Nash did not attend art school, and, while he joined exhibitions of avant-garde artists in the transitional society, the Camden Town Group, he seemed to have had little interest in the cutting edge of modern art. But his most famous painting, Over the Top: 1st Artists’ Rifles at Marcoing, 30th December 1917, is worth discussing at some length, because it captures a moment in time, the brief few seconds before the men depicted were mowed down by machine gun fire. The fact that the soldiers marching stoically towards their fate were artists adds a level of poignancy to the painting, underlining the extent to which the best and the brightest, the flower of English youth, never left the battlefields and never lived out the lives for which they had been trained. But they had also been conditioned to die.

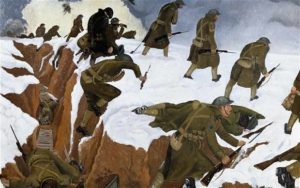

John Nash. Over the Top: 1st Artists’ Rifles at Marcoing, 30th December 1917 (1918)

In an article written in 2014, commemorating the centenary of the Great War, John Lewis-Stempel explained why so many of the well-educated did in this conflict. The discussion had no intention of implying that privileged people should not fight for their country but to underscore how this generation was trained to go to war. As Lewis-Stempel wrote,

..as a Darwinian survival mechanism the public schools of Britain were unsurpassed. They trained a whole generation of boys to be waiting in the wings of history as military leaders. The young gentlemen from Eton and the Edwardian public schools paid a terrible price for this duty. It was a funny old world war, the First World War, but there was one unassailable, and surprising, truth about it. The more exclusive your education, the more likely you were to die. As a rule of thumb 20 per cent of public school boys who fought in the war died, against 13 per cent of those overall who served. There are 1,157 names on Eton’s memorial to its Great War dead, so many chiselled on the wall in the cloisters that it hurts the head to scan them. Historians have a horrible phrase for this difference between the war’s general mortality rate and the public school rate: “surplus deaths.”

In other words, the percentage of deaths among the elite was much higher than those of the middle or lower classes. In examining Over the Top closely, one detail stands out–the men are not holding their weapons as if they intend to fire them. The guns hang limply as if recognizing the futility of firing. The posture of the bodies, the stooped shoulders, the walking gait, all speak of resignation, not a spirited charge. Lewis-Steeple said,

By the rule of the British Army, junior officers were the first “over the top” and the last to retreat..Of course, public school boys were easier for the Germans and Turks to hit. Due to their better diet and general physical fitness they were, on average, five inches taller than their working-class contemporaries in 1914..One might almost say that public school boys had been physically built up for the slaughter. School sport, as the Duke of Wellington suggested, was a key part in their preparation as incipient warriors..Lionel Sotheby wrote in his last letter before he was killed in battle in 1915: “Eton will be to the last the same as my parents and dear friends are to me… To die for one’s school is an honour.”Loyalty is an elastic concept. If a boy could be made loyal to his “house,” his school, he could be made loyal to his country.

To illustrate the point made by Lewis-Stemple, which could be read as those who were trained to lead naturally stepped up when the time came, the unit that Nash depicted was none other than the famous Artists’ Rifles. Today the Artists’ Rifles Association still exists, describing the historic role of this very special group of artists: The 38th Middlesex Rifle Volunteer Corps was formed on 25 May 1860 as part of the volunteer movement which arose after the Crimean War. The 38th was composed of painters, sculptors, musicians, architects, actors and members of other artistic occupations and was based in the Chelsea area of Middlesex. For that reason it was almost certainly informally titled the “Artists’ Volunteers.” The badge of the 38th Middlesex Rifle Volunteer Corps was designed by W.C. Wyon, an original member of the unit and a Queen’s Medallist and Engraver to the Signet. The helmet plate badge had a “Mars and Minerva” design in the centre and had the characteristic Maltese Cross background associated with the rifle regiments. The Artists’ Rifles adopted the ‘Mars and Minerva’ motif as their badge.

During the Great War, many artists simply went into exile, but in England, they stood their ground and fought for their country. The number of artists who demanded to join this unique regiment was so great that the Artists’ Rifles had to be divided into the 1/28th, the 2/28th and the 3/28th London Regiment. And, as the website continued, During WWI, 10,256 officers were commissioned after training with the Artists’ Rifles. They went to the Foot Guards, every infantry regiment and to many of the Corps. The Royal Artillery alone had 953 officers and the London Regiment 738 officers commissioned from the Artists’ Rifles. Nash served in the 1st Artists’ Rifles for two years, from 1916 to 1918, the years in which the Germans dedicated themselves to bleeding the British and the French to death. The Battle of Cambrai was notable because 1917 was the first time the British used tanks in battle in an attempt to break the stalemate of the lines of trenches alone the Hindenburg line. At first the surprise attack on November 20, 1917 worked and the British moved forward. It would take some time for the Allied forces to learn how to effectively implement tanks as an assault force, but in these early months the large lumbering machines were easy targets for German artillery. By the battle’s end on December 4th, the initial success had become a total failure and a complete disaster for the retreating British. During this battle, at which Nash portrayed a futile attempt to advance agains the reformed German lines, the losses were unsupportable: 44,000 killed, wounded and lost in action. As John Nash later recalled, “It was in fact pure murder and I was lucky to escape untouched.”

The painting is noteworthy because despite the active participation of English artists in the Great War, it is rare for them to show actual battle. Nash who was trained from childhood to draw and paint the natural world, depicted the trench, not as a neatly engineered line but as a gash in the wounded earth, zig-zagging raggedly, gouging the winter landscape. But, because his worried brother, Paul, managed to remove John from active combat, the painting was done from memory in the family home in Buckinghamshire. Despite the fact that Over the Top was destined for the British War Memorials Committee, it is a critique of the lack of strategic thinking on the part of the High Command, whose only answer to the mechanized war was to throw more and more men at the machines. As Nash said, “I think the vivid memory of the occasion helped me when I painted the picture and provoked whatever intensity of feeling may be found in it.” Nash, like the soldiers who were going over the top with him were following orders, orders that would surely result in their deaths. And yet, trained in self-sacrifice, they walked into death, as Nash expressed it they were “murdered.” And for the most part, it was not the Germans who were blamed for the “murder,” it was the British commanders.

As the younger brother, now safely in the company of his protective older brother, painted, he healed himself by returning to his first love, nature. As Over the Top illustrated, John Nash felt the assault of the War upon the earth very keenly. Cambrai was located in the farmlands of France and the Memorial, the Louverval, located in Doignies, and is surrounded by verdant countryside. Today the flat terrain is studded by wind farms, but extant photographs of northern France show the terrible toll taken on the trees, which were first chopped down to become flooring or “duckboard” for the trenches and were then destroyed by shelling. For Nash a botanist, the destruction of the trees, of nature was a metaphor for the devastating human loss that turned this part of France into a permanent cemetery. Over the Top shows a routine maneuver, a forward advance of some eighty men but does not reveal the equally routine retreat back to the front lines–sixty eight men did not return–John Nash was among the twelve survivors. No wonder his brother moved heaven and earth to extricate his young sibling from what would have been almost certain death.

The 7th Brigade fatigue party of the Australian 2nd Division passing the “Gibraltar” bunker, Pozières, August 1916

The same ravaged fate of the trees is carefully delineated by Nash in his 1918 painting Oppy Wood, 1917, Evening, a rather ironic name, considered the splintered and torn trees that loom sadly as dead wood hovering over the trenches. The duckboard which lined the walkways of the trenches is all that is left of the sacrifices of the fractured trunks, now shorn of branches.

In his 2009 book Wildwood: A Journey Through Trees, Roger Deakin described Nash’s painting almost as a story of a progressive wiping out of all nature by the merciless demands of a mechanized war. “The trenches consumed vast quantities of wood, since they had to be floored and connected with miles of duck boarding over the mud and water, and often reinforced with wooden stakes to prevent a collapse of their walls. And the stretchers, thousands of them, were of canvas between a pair of ash spars with turned handles.” Deakin quoted David Jones, a Welsh poet who served on the Western Front. Jones vividly remembered the “muffled hammering of wood on wood,” as the trenches were being built. According to the author, Jones “often describes war in terms of wounded nature and the disfiguring of trees and woods,” and provided the eloquent phrase from the artist, “those weeping willows shorn,” which as he said referred to “the ravaging of nature, the dishonoring of the woods, comes to represent the unnatural perversity of the war..The flowers, trees and birds are the only vestiges of anything familiar left in the waste land of the trenches, and they themselves area vulnerable as the soldiers.”

According to Deakin, Nash went off to war, carrying with him a copy of George Borrow’s The Bible in Spain. Written decades after the Peninsula War, this book was published in 1843 and had little to do with religion and read like an true life adventure tale of a man on a mission, to sell Spanish language Bibles to the Spanish. Traveling on horseback through a nation torn by civil war, Borrow wrote colorfully of his encounters with bandits and gypsies, angry priests and self-important academics. The tome was a strange choice for an artist and a nature lover, but the exciting stories must have whiled away the long dull hour before going over the top. As Deakin wrote, Nash “painted the shattered woods on the battlefields of France. They came to stand for the dead and maimed of both sides. Some the action took place in or around woods, which afforded cover of the troops or tanks, until they were blown to pieces. Their skeletons might be the only landmarks left on the trenched and cratered waste land. Nash writes of ‘the trees torn to shreds, often reeking with poison gas.'” It is against this backdrop of memory that Nash painted The Cornfield (1918), his first painting after he returned home safely. John Nash. The Cornfield (1918) In his book, British Art and the First World War, 1914–1924, James Fox described The Cornfield as “a conventional peace picture..Nash’s picture was an attempt to reconstruct the peace after the war. It was also an invaluable tool in Nash’s own personal recovery from the battlefields: a ‘thank you’ for surviving,and a mans exorcizing his traumatic memories so he could begin his life again.” For a long time, The Cornfield and Over the Top stood together, side by side in the studio of the brothers. In contrast to the bleak scarred landscape, scathed and shorn, of Over the Top, The Cornfield had all the hallmarks of English landscape painting. In place of the resigned soldier trudging to their deaths, the stack of corn stand tall and jaunty, leading the way to the pale promising fields beyond. Cupped in a protective gesture on the part of the bordering green trees, the open fields, ripe with cultivation, are bisected by a shaft of benign heavenly light, blessing the bounty. The bright golden light glows in a strong and uplifting contrast to “Stand to” Before Dawn (1918) a painting utterly without light of any kind, devoid of hope. Even the streaks of the rising sun seem feeble and malformed. John Nash. ‘Stand To’ Before Dawn (1918) During the Great War, “Stand to” referred to the twice daily order for soldiers to mount the fire step, as seen in the painting, ready for an attack. Since most attacks took place at dawn, presumably disturbing the end of the long night, or at the end of an exhausting day, at twilight, the order, referred to as “the morning hate,” brought the soldiers to a condition of waiting attention for a half hour or even for an hour. Rifles were loaded and ready, bayonets were fixed, ready to repel any invasion, as the troops Stand to Arms, a daily ritual that began and ended every day with fear. These were the conditions in which the failed attack on Oppy Wood happened. The British attacked in the darkness before dawn, around four, and were silhouetted against the still shining moon. The battle which claimed so many lives was a feint ordered to disguise the main assault which would be elsewhere. To those who died in yet another futile attempt to break through German lines there are no graves, no graveyard, The village of Oppy itself is tiny, without hospitable accommodations of the traveler. The men who died there are mentioned in the memorial of Arras, the main objective. Sadly, John Nash lived long enough to repeat his performance as an Official War Artist, during the Second World War, the last attempt of the Germans to dominate Europe. If you have found this material useful, please give credit to Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.