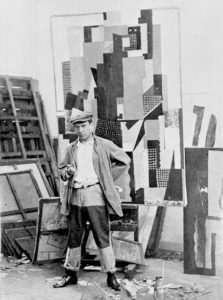

Making Parade (1917)

Pablo Picasso during the Great War

Part One

Pablo Picasso was bored. Paris was empty of the stimulating company he had grown accustomed to. His partner in Cubism, its invention, its evolution and its four year development, Georges Braque, had patriotically enlisted and was fighting in the trenches, using guns instead of paint brushes. His German art dealer, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, had been declared an enemy alien, his merchandise, including many works by Picasso himself and Braque, had been sequestered by the French government. Albert Gleizes, not necessarily a good friend, but who was at least a fellow artist, had done his time for his country and had mustered out in 1915, spending the rest of the War in New York, joining Marcel Duchamp in exile. The elder Duchamp, Raymond Duchamp-Villion was also serving as a medic, taking care of the war wounded. Most keenly felt was the absence of his supporter in print, the art writer and poet, Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918), who was actually Polish and Russian and rather old for the military at age thirty five, but had patriotically gone to war to fight for France.

Apollinaire had been the center of the pre-war avant-garde, organizing the artists and creating a discourse on their art out of his studio visits and café conversations with them. Now he was in the 38th artillery regiment, handling the big guns, the famed Canon de 75 modèle, invented in 1897. Now he was part of a team of twelve, six men, each with a specific task, and six horses with one job–tow the wheeled gun. Apollinaire reveled in the physicality of the labor and found enough private time to produce a body of war time poetry. “I so love art, he said, “I joined the artillery.” Picasso was not so inspired. While others had sacrificed their art careers for an uncertain future on the battlefields, Picasso remained behind, continuing his own artistic endeavors–alone. His remaining confident, Gertrude Stein, American poet and art collector, received word of his unhappiness about the absence of his companions. “Will it not be awful, when Braque and Derain and all the rest of them put their wooden legs up on a chair and tell about the fighting?” he asked her, not understanding the realities of war at all.

From the perspective of Picasso, a supremely self-centered individual, the list of those absent was too long. It was as if Paris had been emptied out of its fabled art world, leaving Picasso, a citizen of a neutral nation, Spain, in the city, bereft of suitable companionship.To add to his sadness, his most recent lover Eva Gouel (1885-1915) , died in 1915. When she arrived in Paris, Gruel had taken a new name, Marcelle Humbert, but returned to her birth name at Picasso’s instigation. Part of a complex plot of secret affairs, Eva had been a friend of Picasso’ current lover, Fernande Olivier, who was having a clandestine affair on the side with a Futurist painter, Umbaldo Oppi. It is difficult to sort out the complications but according to one account, Fernande asked Eva, the mistress of Marcoussis, to keep her secret. Eva, instead, embarked on her own secret liaison–with Picasso. One of Picasso’s most salient works of pre-war Cubism was Ma Jolie of 1911, in which he sent a coded announcement of his new mistress. Fernande and Picasso predictably went their separate ways, and he wrote to Braque, “Fernande left today with a Futurist painter, what shall I do with the dog?” Once he and Eva moved in together, Picasso began taking Russian lessons from a Baroness Helene d’Oettingen, who demanded a great deal of his time, leaving Eva at home and coughing. When she was admitted to the hospital, where she would die of tuberculous, Picasso visited her by day and entertained himself with a new mistress at night. When she died in mid December of 1915, he wrote to Stein, “My poor Eva is dead.. she was so good to me.”

Pablo Picasso. Ma Jolie (1911)

Other deaths would follow, but after Eva’s passing, Picasso needed distractions. Without the avant-garde artists within the Cubist circles to compete with, without Braque to collaborate with, he embarked on a new brand of Cubism. This new Cubism, Picasso’s alone, was pure painting, but this phase bore traces of the now discarded experiments with collage and are material acknowledgments of his changed circumstances. First, Kahnweiler was no longer his dealer and, because of the War, the traffic in Cubism flowing east to German clients ended; and, second, once Kahnweiler went into exile in Switzerland, Picasso needed a new dealer to look out for his interests. The problem for Picasso was that many of Kahnweiler’s clients were not French, or to put it another way, there were almost no collectors in France for Cubism in 1915. The Steins had moved on, disliking Picasso’s new works years before the War, leaving Léonce Rosenberg (1879-1947) and André Level (1863-1947) as almost the lone supporters available for Picasso. In their own ways, both men were very significant to the next phase of the artist’s career. It was Level who had masterminded the famous Peau d”Ours auction in the spring of 1914. In this auction, a pre-Cubist work by Picasso fetched the highest price, but the true implication of the event was not that Picasso could be a bankable artist but that avant-garde art itself could be a profitable enterprise. Keeping in mind that Parisian buyers were inherently conservative and historically hostile to Cubism, it appears that Picasso made a decision to tame Cubism for financial reasons. One can deduce the process simply by noting the evolution of his art after Braque went off to war in August of 1914 in terms of what he did not do–mixed media–and what he actually executed–paintings that began to resemble painted collages, large blocks of color offset with stippled textures. In other words, Picasso began doing “Cubism” for prospective collectors and “Picassos” for wary buyers. His experimental period was over, and Picasso would remain cautious about being too avant-garde until he was was well established as a successful artist. One can see his desire to reap the rewards of his years of innovation with an eye as to what prospective buyers would want.

Indeed, Kahnweiler’s Cubist artists, now “abandoned,” as Rosenberg would have it, were in dire straits, needing to be rescued by a new dealer with deep pockets. Level did not have the funds but Kahnweiler’s only Parisian collector, Léonce Rosenberg, founder of L’Effort moderne, an enterprise dedicated to promoting Cubism, was able to step into the breech and assist Picasso. Although history would consider Léonce a less serious collector compared to his brother, Paul, a prominent art dealer, during the War, his support was pivotal for Picasso and the Cubists. However, it should be stressed that, before the War, the Cubism of Picasso and Braque was available only in Kahnweiler’s now closed gallery, mostly sold east, and thus was more of a rumor than reality to the the Parisians. For this art audience, compared to that of Berlin, the “Cubists” were the Salon Cubists, led by Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger, who excelled in a colorful and conservative version of “Cubism” that the traditionalists absolutely hated. Apparently understanding the already formed tastes of the potential clients, whether he wanted to acknowledge them or not, Picasso veered in the direction of the Salon Cubists and it is out of this wartime enterprise that his work for Parade (1917) is to be understood.

t

t

One of the best known works of the wartime oeuvre was Harlequin (1915) clearly indebted to collage, with its large areas of color blocks, the assertive diamond pattern. At first glance, this work is a nod to Picasso’s conservative and acceptable past, the Harlequin paintings of his Rose Period. The now strong and intense colors put him more in line with the Salon Cubists, while Matisse, during this same time, went dark, giving up his former bright colors as if fasting for the War. However, it is also clear that the clown is also the artist, saddened by the end of a productive phase in Picasso’s artistic life and lonely without his “band” of supporters. However ambiguous, the return of the character, Harlequin, would attract another admirer, the poet Jean Cocteau (1889-1963). According the Michael FitzGerald’s Making Modernism. Picasso and the creation the Market for Twentieth-Century Art (1996), Picasso was uncomfortable with being associated with Rosenberg’s Salon Cubists, and Cocteau pulled him towards a more eclectic destiny. Cocteau, like many young French men, served in the military as a medic, a posting that seemed to allow him to continue his work as a theatrical producer during the War. Working with Cubists artists, Albert Gleizes and André Lhote on A Midsummer Night’s Dream, a venture that did not take place, Cocteau revealed a willingness to work with avant-garde artists and turned his attentions to Picasso himself. Once he was out of the army in 1916, he joined forces with composer Eric Satie and they imagined a new and thoroughly modern spectacle, Parade, a ballet with American references. In order to make the proposition of a contemporary ballet attractive to the Ballet Russes, Cocteau courted Picasso, who was ripe for new experiences, and pulled him into the ballet project. By the fall of 1916, all the pieces were falling into place, with Serge Diaghilev, approving the group of artists–Léonide Massine, the choreographer, Cocteau, the playwright, Picasso, the costume and set designer, Satie the composer– and their ideas for what would become a Cubist ballet. In a letter, Cocteau noted that Apollinaire was “helping” Picasso, who was moving to a new abode in a suburb of Paris. Picasso was becoming mainstream.

In A Day with Picasso (1986), Billy Klüver described how Parade forced Paris to accept Cubism: “There was a growing acceptance on the Right Bank of the music of Satie..and of the new poetry of Apollinaire and Reverdy, but Right Bank resistance to cubist painting was still strong..” Klüver quoted Cocteau as saying, “A dictatorship hung heavy over Montmartre and Montparnasse. Cubism was going though its austere phase..To paint a stage set for a Russian ballet was a crime..” Klüver continued,

Cocteau in his collaboration with Picasso introduced cubism to the Right Bank in such as way that it could not be ignored. In May 1917, the aristocratic patrons of the Ballet Russes were still not ready to accept the cubist sets and costumes with open arms and Parade created a scandal when it premiered. But the ice was broken, and Parade set the stage for wholesale acceptance of these modern masters after the war..It was through his involvement with Cocteau and Parade that he moved into circles around Diaghilev and the Ballet Russes and into personal contact with the dynamic and influential group around art patrons like Comete Etienne de Beaumont and Mme. Eugénia Errazuziz. They began to acquire his work, and about a year later the quintessential Right Bank dealer Paul Rosenberg began to buy paintings.

This famous ballet, Parade, was described as a “ballet réaliste” by Cocteau and Satie. Short, in comparison to its subsequent fame, twenty minutes of modernity, sandwiched between Les Sylphides, Petrouchka, and Le Soleil de nuit. The company dancers had to switch corporeal and psychological gears from one style of choreography to another. Despite its modern theme, the mood for Parade, a rather antic ballet, was a nostalgic one of lost innocence. The ballet juxtaposed modern corporations and the world created by dull business, especially in modern cities–mainly New York and its emerging skyscrapers–to the unbridled joy and absurdity of the old fashioned circus. As Juliet Bellow pointed out in Modernism on Stage: The Ballets Russes and the Parisian Avant-garde (2013), the characters of the Managers in Parade was analogous to the lecturer for old fashioned slide lecture, speaking in relation to a visual image, explaining its meaning. She wrote,

If reads as film exhibitors or lecturers, Picasso’s Managers further destabilized the relation of reality to representation in Parade. At first glance, these manifestly artificial constructions contest with the “real” (that is non-Cubist) bodies whose performances they announce. But as film exhibitors, the Managers would constitute the live portion of the program, transforming the parade numbers into moving pictures. Without their spoken dialogue, however–which to reiterate, Picasso insisted on removing–the Managers could not securely occupy this role. Moreover, Picasso’s flattening costumes, Satie’s caricatural accompaniment and Massine’s stilted choreography refused any body onstage full presence. Even if the dancers were taken to be live performers (which of course, they were), the artifice foregrounded in this production estranged hem from coherent embodiment. The entire production became a hall of mirrors, a proliferation of corporeal copies that challenged he integrity of the original.

Sitting in the audience opening night, the poet Apollinaire, watched the ballet in amazement and scribbled the new word, “Surrealism,” on his program. The next post will continue the examination of Parade and its layers of realities, so dense that a new term was coined.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.