Making Parade. Ballet réaliste (1917)

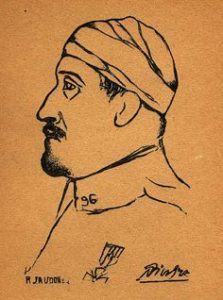

Pablo Picasso during the Great War

Part Two

When Guillaume Apollinaire (1888-1918) scribbled the word, “Surrealism” on his program for the new ballet, Parade (1917), on May 18, 1917, he added a new word to the art dictionary. He later included a substantive definition, of sorts: “When man wanted to imitate walking, he invented the wheel, which does not look like a leg. Without knowing it, he was a Surrealist.” The poet liked the term and all that it implied and used the terminology again for his own play of the same year, Les Mamelles de Tiresias. As his biographer Wayne Andrews explained, Apollinaire himself had origins one could describe only a surreal. His mother was Russian but his father was mysterious and unknown, but he may have been “the illegitimate son of the duke of Reichstadt, the only child or Napoléon I and Marie-Louise of Austria.” His mother Angelica took Guillaume and his brother, also of unknown origins to Monte Carlo with her latest lover, who later took his makeshift family to Belgium. When the mother and children were abandoned, they left then spa hotel without paying the bill and, when they arrived in Paris, the police promptly arrested them. The charges were eventually dropped and Wilhelm Albert Włodzimierz Apolinary Kostrowicki, now Guillaume Apollinaire, a budding poet, worked as a bank clerk, a pornographer and author of Mirely (1900), and a tutor. By 1911 he was established as an art critic and as a poet but somehow he was entangled in the theft of the Mona Lisa, because he had stolen two Iberian heads from the Louvre as gifts for his friend Pablo Picasso, who wisely returned the sculptures to the museum. Apollinaire briefly went to jail and Picasso pretended not to know the light-fingered poet.

Their friendship recovered from this rather strange setback, and the two misfit, one Russian and one Spanish, artists in Paris remained friends to the end, which sadly came soon. Guillaume Apollinaire weakened by a head wound, died of influenza in November of 1918. In his article, “I Seem to be at a Great Feast: the War Pomes of Guillaume Apollinaire,” TonyHoagland, described the odd circumstances of his being struck by stray shrapnel: “In March 1916, while reading a Paris newspaper in the trench, he was struck by a flying piece of shrapnel that pierced his helmet. He realized he had been wounded only when blood dripped onto his paper. The shrapnel was extracted, but his condition complicated; he was trepanned at a battlefield hospital and eventually sent back to Paris.” Thanks to this event, Apollinaire could return to his former career as poet and critic and could be present at the performance of Parade at the Théâtre de Châtelet that May evening in time to view a new art form. The ballet Parade combined disparate musical tendencies, clashing but totally au courante, a jarring experience described by Christopher Schiff as “a compromise of French theatrical music and Futurist noise.”

The unlikely concoction, a mash-up of avant-garde impulses in art and music, Parade was Picasso’s opportunity to get out of a Paris, darkened by a lingering war, and to test himself in a new discipline, theater. The performance, for which Picasso did the theater curtain or the rideau rouge, the costumes and the sets, established him as a contradiction in terms, a successful avant-garde artist. Before the Great War, the avant-garde artists in Paris lived precariously, dependent upon a few art dealers willing to attempt to sell their wares. The most famous or infamous Cubists in Paris were the Salon Cubists, who did handsome paintings, colorful interpretations of the late works of Paul Cézanne. Long scorned by art history, which officially labeled them as “minor Cubists,” these artists were, in fact the ones who carried the burden of the outrage of Cubism through their public exhibitions, while Picasso and his partner, Georges Braque, were able to work in their studios in private, supported by their German art dealer, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler. To the mainstream art audience which frequented the Salon des Indépendents and the Salon d’Automne, Picasso and Braque were better known through their reputations for being advanced than for their actual works. But when the Great War began in August 1914, Picasso abruptly lost his German dealer and his German clientele. As was discussed in the previous post, he was forced to find Parisian support, but perhaps most importantly, the artist, a Spaniard, did not have to serve in the military. While the lives and careers of the other avant-garde artists were interrupted–indeed, some of these artists never came home–Picasso, protected by his nationality, was able to continue to develop his art.

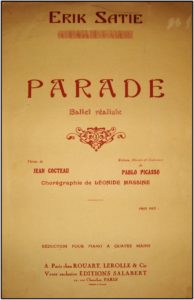

Moving fluidly to a tamed and commercial version of Cubism, Picasso redefined himself as a more marketable artist to his Parisian dealer, Léonce Rosenberg. But parallel to the new conservative and decorative turn in his Cubism, Picasso was experimenting with a return to an Ingres-like classicism, signaling that he was bored with Cubism and wanted to move on. One could make a case that Parade is the last great statement on Cubism from Pablo Picasso and that it is his farewell to his former life, before he began a new stage for his career. The Ballet Russes was no stranger to scandalous ballets and it might be suspected that impresario Sergei Diaghilev used the occasional whiff of frisson as counter punctual shocks to his more conventional performances. Dressed as a Harlequin, Jean Cocteau had approached the famous Cubist artist Pablo Picasso paying homage to Picasso’s recent painting in hopes of assembling a truly avant-garde group of artists to attract the attention of Diaghilev. Cocteau wanted his own scandal, and, apparently, so did the composer Eric Satie, who was his co-creator of Parade. The ballet, on the strength of a one page script, would be put together in Rome.

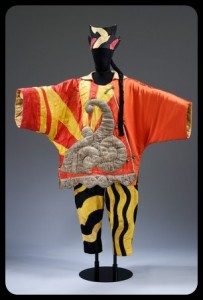

Given the nationality of the Ballet Russes, its leaders and its dancers, it was impossible to return to Russia, and, for the duration of the War, the company was exiled, so to speak, in Rome. When Picasso, not a great traveler, arrived in the city, he was thirty five years old, ready to settle down as a married and respectable artist. However, his most recent liaisons, after the death of Eva, were not exactly women of virtue. Instead Gaby Lespinasse and Irène Lagut, culled from the ranks of artists’ mistresses, loved him and left him, moving on to other destinies. It was by chance that Picasso found himself in Rome, without a current lover, and was offered an opportunity to marry beyond his station, something artists seldom managed to do. Always open to new women, Picasso set his sights on one of the dancers, Olga Khokhlova, the daughter of a colonel, an engineer for the Russian railroad. As John Richardson, Picasso’s premier biographer noted, Olga was a “lady” to be courted, wooed and wed, in a proper fashion, because, as the author said, she was “unbearable.” In the midst of flirting with Olga, Picasso had to learn how to be a set designer. Most of his Cubist paintings were of modest size, following his larger earlier works, such as Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). By 1915, the size of his paintings again increased as did the intensity of the color, but the art of working for a viewer who would be close the the work was quite different from creating costumes, for example, that had to be read at a distance. The gifted costume and set designer, Léon Bakst, of an entirely different generation and state of mind from Picasso, nevertheless taught him which colors worked best on stage.

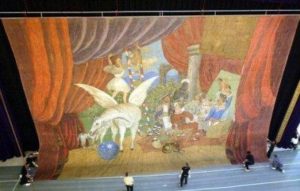

Picasso and his assistants, working on the theater curtain

Picasso also worked with the young second-generation Futurists, Enrico Prampolini and Fortunate Depero, who would become Fascist artist of aeropittura after the War. Their decorative and graphic combination of Cubism and Futurism, easy to read and suitable for mass audiences, gave Picasso an idea of the fate of avant-garde art in the future but also suggested a way to capture the attention of the resistant ballet goers. Indeed, one can find traces of Futurism in Parade. When Futurism was first introduced in Paris in 1912, the Italian entry into the avant-garde stakes, was summarily rejected by the Cubists. But in Picasso’s work for the ballet, Futurism, far more than the rather staid and static Cubism, was better suited to the energetic circus theme.

According to Roland Penrose, Picasso had always been receptive to Futurism and was fond of Boccioni who, by the time, he was in Rome, had died in battle. Between tours of Rome and Naples, viewing works of ancient and classical and Renaissance art that would inform his work of the 1920s, Picasso began to make Parade his own, boldly changing Cocteau’s ideas, including stripping spoken dialogue in favor of pantomime. He added three Managers and a Horse, challenging the poet at every turn. Picasso took over the curtain that was to be closed during a rather long prelude composed by Satie, realizing that it had to be more interesting than Cocteau’s ideas that the drape be emblazoned with the names of the performers, like a still in a film. Indeed the entire ballet is an homage to popular culture, the circus and the music hall, vaudeville, Wild West shows and even American silent films, especially those of Charlie Chaplin.

Satie wove in ordinary songs sung by everyone, popular ragtime, all punctuated by unexpected noises, trains, dynamos, planes. Picasso was fascinated by puppet shows and street theater in Italy, particularly in Naples, and began including local Italian elements. As Satie, his collaborator in thwarting Cocteau, wrote, “Parade is changing, for the better, behind Cocteau! Picasso has ideas that please me better than those our Jean! And Cocteau doesn’t know it!” Of course, Cocteau did not remain in the dark and came to accept Picasso’s perspective on his libretto which, to be truthful, really rested upon the vision of Picasso.

The now-famous curtain was a case in point. When the ballet finally opened in Paris at the Théâtre du Châtelet, in May, the news from the Western front was terrible. The battles of the Somme and Verdun had caused massive casualties and France was bleeding young men, as an entire generation was being wiped out. In such an atmosphere, the audience, already hostile to Cubism and to Picasso, expected to be disrespected and confronted with a style they had been taught to hate. Due to the nationality of Cubism’s dealer, Kahnweiler and his main clients, Cubism was thought of as not French, but German, and the audience in wartime were bristling in anticipation. But the rideau surprised and calmed them. The great drop of cloth recalled a French circus poster, referenced Edgar Degas, Georges Seurat, and Toulouse Lautrec, who were on the verge of being acceptable to mainstream culture mavens. Instead of a Cubist assault, the audience was treated to a fairy tale version of an enchanted circus, like the Cirque Médrano, something loved and remembered from their childhoods. In fact, Parade, as the name suggested, was inspired by the fête foraine, an annual event in which a group of circus performers would execute a few short scenes, according to musicologist Nancy Perloff, on a platform or small stage, a parade. Although this kind of entertainment was long extinct, it had survived in the form of advertising and the word “parade” implied a spectacle, a concept that inspired Cocteau, Satie and Picasso. So at first, the audience could enjoy a comforting nostalgia, the faint perfume of the past.

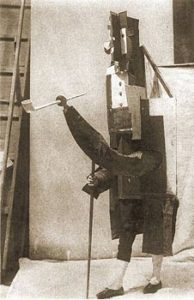

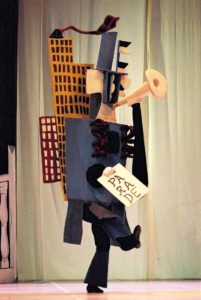

However, once the curtain rose, Cubism, accompanied by Satie’s now lively music, laced with modern sounds, such as typewriters and refrains borrowed from jazz, appears. The three Managers, so large they constituted moving scenery, asserted themselves. The ballet dancers inside were miserable, and the audience, outraged at the Cubist designs, found their worst fears realized. Shouts of “Go back to Berlin” and accusations of “Shirkers” and “Draft dodgers” rocked the theater. Massine’s deliberately awkward choreography did little to calm the outraged reactions, and the audience threw oranges.

When Apollinaire rose in his sky blue uniform, his head bandaged in the honor of France and pleaded for calm, some order was restored. The plot itself was simple: a Chinese magician, a young America girl, inspired by Mary Pickford, and an acrobat from the Rose period, street performers, worked onto boulevard to lure the public into the circus.

The Managers, with skyscrapers on their heads, were their exploiters and the villains of the piece. For Cocteau, the meaning was symbolic, for the audience the meaning was lost in the presence of the dreaded Cubism, for the critics, Parade was shark meat and they spiritedly attacked in a pack. Satie, who had been slapped by a member of the audience, was accused of bochisme (being German) and his exchanges with his critics resulted in lawsuits that bankrupted him.

The accusations of being a traitor to France were unjust for Satie’s music included and consisted of the sounds of modern Paris itself. As Barbara L. Kelly noted inMusic and Ultra-modernism in France: A Fragile Consensus, 1913-1939,

Parade confirmed Satie’s central role as a harbinger of the new. It marked a shift in musical priorities from a focus on sonority and exoticism to a search for inspiration in the mainly Parisian everyday. In common with many of his peers, the ballet also represents a move away from narrative towards abstraction, a tendency that was becoming increasingly important in the dramatic ventures of Stravinsky and Diaghilev..

Of course, in time, Parade would become recognized as one of the great avant-garde ballets of the twentieth century, a classic, the first Cubist theatrical event, but on the 18th of May, 1917, once again, only Apollinaire was capable of rising to the defense of the collision between fine art and popular culture, France and America, sophisticated music and ordinary sound, poetry and farce, delivered in the spirit of the new visual invention, film. As he wrote for L’excelsior, contemplating his own notes on the program, about the idea of “surrealism,” which he understood in terms of a Gesamtkunstwerk, or a new realism:

From this new alliance, for until now stage sets and costumes on one said and the choreographer on the other side had only a sham bond between them, there has come about, in Parade, a kind of super-realism (sur-réalisme), in which I see the starting point of a series of manifestations of this new spirit (esprit nouveau), which, finding today the opportunity to reveal itself, will not fail to deuce the elite, and which promises to modify arts and manners from top to bottom for the wold’s delight, since it is only common sense to wish that arts and manners reach at least to the same height as scientific and industrial progress.

The result was a layering of literature, painting, dance, and music, each coming from a different sphere, far removed from the traditions of classic ballet. Parade dragged dance into the modern world, laid the foundation for artists like John Cage to reconsider the role of noise, and provided Picasso with the caché in world of the Right Bank. He was now a suitable match for the highly ranked Olga. For Picasso, Parade had served its purpose.

The bad reviews, the elimination of the ballet from the repertoire of the Ballet Russes, Satie’s quarrels with his detractors were mere backdrops to his eventual marriage to Olga and his entrance into bourgeoisie life. Apollinaire died two days before the Armistice, and Parade would be revived in 1920. According to Mary E. Davis in Classic Chic: Music, Fashion, and Modernism, Americans loved Parade and, even after its disastrous Parisian premier, the young nation responded positively to a ballet that displayed such unabashed love of American culture. Unlike his former partner, Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso emerged from the War, a prominent artist, ready to preside over the post-war art world, an old master before he was forty. His dealer was Paul Rosenberg, who found him and his elegant wife suitable lodgings in the rue de la Boëtie. By the end of the War, the Spanish avant-garde artist had found his place in Paris at last.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.