Matisse at War

The Dark Period, Part Two

The Great War proved to be an important transition for Henri Matisse (1869-1954), out of Fauvism, an excursion into Cubism, a walk through dark despair and, finally, a breakthrough into the sun. For any artist, finding the next act is always a difficult endeavor. One one hand, Matisse had established a recognizable signature style, and a very specific view, but on the other hand, by 1913, the artist had begun to feel the need to separate himself from the surrounding Fauves and to seek new territory. When Matisse wrote his famous manifesto, Notes of a Painter, in 1908, he was already thirty nine years old, a mature artist, writing a philosophy that would come to define him:

What I dream of is an art of balance, of purity- and serenity, devoid of troubling or depressing subject-matter, an art which could be for every mental worker, for the businessman as well as the man of letters, for example, a soothing, calming influence on the mind, something like a good armchair which provides relaxation from physical fatigue.

If one reads Notes of a Painter in context, Matisse is clearly attempting to distance himself from radical artists who would, perhaps, make a succès de scandale and then fade. Being a “Fauve” had paid off but now he had to reassure prospective patrons such as Sergei Schchukin the an artist who caused sensations was also a serious artist. It was during this year, 1908, that the Russian collector commissioned Dance, one of the great works of the early twentieth century. Pablo Picasso, who would later emerge as an artist who might be Matisse’s equivalent in statue, was but an up and coming Spanish expatriate searching for his own style. Matisse became known for his luxurious works of art, denoting an indolent lifestyle of decorative opulence. His color range, from bright to soft, rippled across is canvases, like the textiles of his native town, Bohain-en-Vermandois.

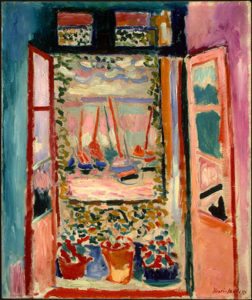

Henri Matisse. Open Window (1905)

The artist, however, was far more conservative in his practice than the Fauve reputation would suggest and Matisse carefully managed his career, attempting to control his reputation. As Catherine Bock-Weiss pointed out in Henri Matisse: Modernist Against the Grain,

In the early years, 1905-1914, Matisse’s reputation as a fauve, or wild beast, resulted from his experimentation with strong color, willful distortions, and reductive simplicity. he was accused of being a madman, fraud, or at the very least an irresponsible “bohemian” (Parisian graffiti had it that matisse’s paintings along with drinking absinthe and using leaded paints, caused insanity,) As soon as his work first began to receive attention, Matisse granted interviews to a carefully chosen few. The resulting articles stress his long apprenticeship in traditional modes, his trusting to instinct while always being guided by a tradition-sanctioned principles, the continuity and logic of his successive styles (to answer critics who accused him of fetching novelty) and especially his absolute sincerity in seeking to realize his own personality. Each interview was timed to comment on the latest exhibition of his most difficult new work..Each pre-1914 article utilizes an identical trope: the author interviewer expects an eccentric or morbid artist, and behold! he or she finds a handsome, wholesome bourgeois gentleman, his speech is seasoned and articulate, in an elegant home and spacious studio, Matisse controls the entire encounter by receiving these interviewers i his home or studio, by walking them through his collection of art and artifacts, as well as commenting on the development of his own recent work from early examples to the most recent. The artist’s scandalous reputation creates a repoussior effect against which the description of the artist’s appearance and environment is all the more striking..

But five years later, Picasso was a major competitor and four paintings by Matisse had been burned in effigy by angry art students in provincial Chicago. Matisse, who had shocked Paris now sparked outrage at the 1913 Armory Show. For an established artist, well on his way, these reactions were annoying. It was time to move on.For a four year period, Matisse seemed to be engaged in a series of experiments with Cubism, perhaps due to his friendship with Juan Gris. The year the Great War began, 1914, was the year of a shift towards a more rigid structure with diagonal and vertical lines, with a more monochromatic range of hues. Matisse did a series of five canvases on a bowl of goldfish in his studio at the quai Saint-Michel. He was revisiting, redoing, a topic he had painted previously and endowing it with a dark rectangle dividing the center of the canvas.

Henri Matisse. Goldfish with Palette (1915)

In her book on Matisse, Carolyn Luncher suggested that the black stripe which divided the goldfish, the observed, from the observer, the palette of the artist, that Matisse was paying homage to Picasso’s Harlequin. But the painting of a harlequin mentions and pictured by Luncher was not painted until 1915, a year after the goldfish series, therefore, it seem far more likely that Matisse was re-reading one of Braque’s papier collés. His greatly simplified color palette changed to dark grays, black, green and blue, as seen in Vue of Notre-Dame (1914).

Henri Matisse. Vue of Notre-Dame (1914)

This color scheme appears in Portrait of Woman on a High Stool (1914) of which Alfred Barr, Jr. said, “Except for a few touches of reluctant colors, all these austere forms exist in grey monochrome,” and Portrait of Yvonne Landsberg (1914). In July of 2010, Blake Gopnik pondered these dark works:

His “Woman on a High Stool” has just that gray-and-watercolor range, as does his “Bathers.” His “Goldfish and Palette” has a sense of having first been composed in black and white, as many Matisses from this era literally were. And then you can imagine Matisse, the retoucher, picking out its most important details in their iconic colors — in “goldfish orange,” “sky blue,” “tangerine orange” and “leaf green.

Henri Matisse. Woman on a High Stool (1914)

Henri Matisse. Portrait of Yvonne Landsberg (1914)

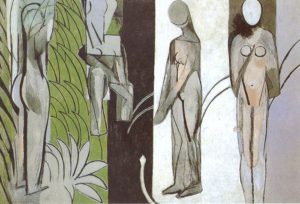

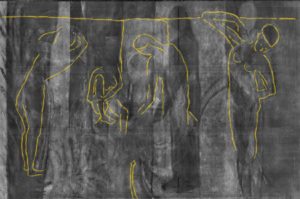

Carried over to his monumental re-examination of Cézanne’s Bathers, Bathers by a River (1909 to 1917). In the previous post, the way in which this canvas was altered from graceful bathers to geometric rigid bathers and pre-existing vivid colors painted over to be recovered through incisions and scrapings on the part of the artists himself.

Bathers by a River (1909 to 1917)

Earlier version recovered by X-ray

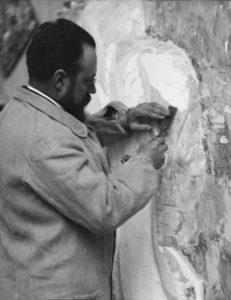

Matisse gouging into the surface

This four year period is so odd, such an outlier, in the oeuvre of Matisse, that art historical accounts of his career often skip over these unexpectedly dark paintings, moving quickly on the his 1917 trip to Nice. It was here, despite the bad weather, the failure of the battles of the Somme and Verdun to end the Great War, that Matisse was able to pivot to the mature work of his middle years. In writing in The New Yorker on July 18, 2016, of the seaside city in the wake of the terrorist attack on its citizens, Peter Schjeldahl recalled,

Nice is a city smitten with the sea. If there were more sea, there would be more Nice. As well, there would be more ways to relax if more ways existed. Walking the esplanade becomes strolling, the rhythm of a general letting go..Nice is associated with artists who have gone there, but that’s happenstance. With one major exception, the greatest minds and talents are no more immune than the less great to being unstrung by the city’s lazy raptures. Ambitious work happens elsewhere. The exception is Henri Matisse, whose reward for his years in Nice and thereabouts, from 1917 until his death, in 1954, was precisely a relaxation of spirit that harmonized peak achievements of modern style—strenuously realized in Paris—with unrushed rhythms of sea and air.

It seems as if Matisse went to Nice to be closer to his son, Jean, who was stationed at Marseilles. He arrived in Nice on Christmas Day. The “pig of a hotel” also known as the Hôtel Beau-Rivage, was cold, but, as Matisse later wrote, “When I realised that every morning I would see this light again. I couldn’t believe how lucky I was.”

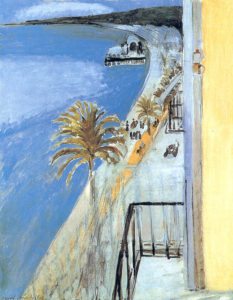

Henri Matisse. The Bay of Nice (1918)

Basking in the colors coaxed forward by the Mediterranean light, “soft and tender despite its brilliance,” as he said, Matisse would live in this hotel until April of 1918. It was here that he set up his studio and began a series of paintings that would define his oeuvre until 1930: undulating sensuous odalisques in decorative interiors. In her article “Painting the Light,” Dorthe Aagesen explained that

..his relocation to Nice was universally regarded as watershed moments in the artist’s development. Matisse had recently turned away from an experimental mode that had resulted in some of the most austere innovative compositions of his career..The change of scene and lifestyle afforded him the opportunity to reflect on his intense artistic efforts over the past few years, as well as a change to test a new course. A closely linked series of interiors dating from his first moths in Nice became a vehicle for this new outlook and direction.

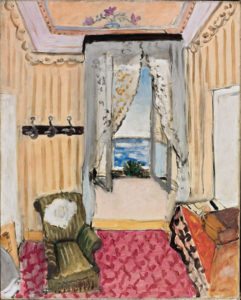

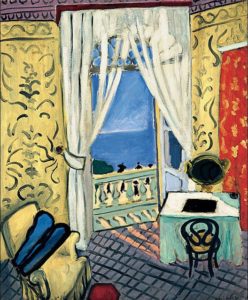

In her discussion of the sudden change in his work, Aagesen provided an interesting point of comparison with Matisse’s series of “window” paintings: In a letter to his wife, Amélie, dated December 31, 1917, he remarked ‘The weather..was very beautiful this morning so I quickly ran to my ’15’ canvas and did a view from my open window. I am not too dispelled with it.” After years in a Paris wreathed in funeral gloom during the war, Matisse had walked into a different world, existing adjacent to a port city at war but tucked away in a crescent shaped scoop in of the coastline. Confronted with nature at its most beautiful, Matisse stayed indoors. Compare to his early landscapes at Collioure, Matisse settled down to interiors, perhaps alluding to a domestic safety and ease. The artist gazed out of the tall open window of his hotel room, viewing the sea and the distant landscape, backed up to a central spot in his space. “Most people come here for the picturesque quality. As for me, what made me stay are the great colored reflections of January, the luminosity of the daylight,” he said.

Henri Matisse. My Room at the Beau-Rivage (1918)

But is was at Collioure twelve years earlier that Matisse presented his familiar Open Window in 1905. His open window in Nice returned to his Fauve roots, but Fauvism and its deliberate experimentation had gone through the same process as Cubism: it was tamed and contained and softened, shaped into new signature “Matisses.” One can only imagine how comforting this quite interior of white curtains fluttering in an ocean breeze would have been to a war weary nation. The solace sought and found by the artist is palpable in this interior/exterior motif. It would not be totally correct to assume that the change from dark to light was complete, for there are images he made during 1918 that bear lingering traces of the rigidity of Cubism and its darkened colors.

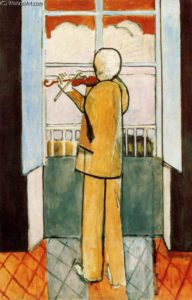

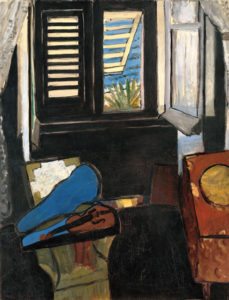

Henri Matisse. Violinist at the Window (1918)

Henri Matisse. Interior with a Violin Case (1918)

The images of the violinist seem to be a Parisian interior, the dour colors contrasting clearly with the soft bright Nice interiors. However, the Interior with Violin has two versions, with the first clearly a transition out of Cubism during the first months of the year 1918. The painting that spanned 1918 to 1919 was actually a third version of the hotel interior in Nice, transformed, as Aagesen noted, because “large areas of the surface were painted over in black. Light was pushed out of the room, which now harbored a darkness that contrasted with the brightness outside. At the same time, the light seemed to penetrate the room precisely because of the black color..paradoxically, the black proved to be the strongest means for expressing the brightness and clarity of light.” The author also noted that, while he was in Nice, Matisse took the opportunity to make contact with the venerable artist, Pierre Renoir. The two artists discussed their favorite topic: light and color; but they approached the problem of conveying light in very different ways. Matisse showed Renoir the early version of Interior with Violin and the artist was astonished at the copious and unexpected use of black. When explaining how black worked as light emanating from the interior of the canvas, Matisse said. “It is constructed with an ensemble of forces that has nothing to do with a direct copy of nature.”

Henri Matisse. Interior with Violin Case (1918-1919)

The last winter of the War was a turning point for Matisse, a time in which he began to see a way clear to his next stage, but then news from the Front was not good. The Germans attempted one last advance, using their huge guns to shell Paris and what was left of their army to subdue Picardie, where Matisse’s mother was copying with the German occupiers of her town. By Spring the danger seem to have dissipated and Madame Matisse and the children moved to Nice to be with Matisse, who, now that the weather was clearing up, took to exploring the new landscape of Cote d’Azure. His son Jean seemed safely out of danger and Pierre was coming into his own, but then the offensive recommenced and the Germans threatened Paris in May. It was at that point that the Hôtel Beau-Rivage was taken over by the military and the Matisses rented rooms in a house that overlooked the port but lacked a direct view of the sea. The artist would rise at dawn and, facing east, would watch the sunrise, spirit reviving in the light. The Matisses were safe in Nice, but Paris was still being shelled and Pierre signed up for what would be the end of the War, in time to serve in the Second Battle of the Marne. This would be the last battle, which would be part of the effort to halt Germany’s last attempt to win the War. By August, the lines were almost back to normal, at the stalemate formed at the end of 1914. But the cost of the final battles were high and Germany suffered 640,000, including Imperial stormtroopers, the Sturmtruppen, the last of the best and brightest in the nation. Using Hutlier Tactics, or striking at weak points only, these elite fighters succeeded in moving sixty miles towards Paris, but they moved too far too fast and the Allies began to press the Germans back, with Americans arriving in Paris at a rate of 10,000 a day, entering into the fray, on hand for the final kill. From August and on into September the Germans were surrendering en masse. As Stephen Tempest wrote,

The German army had pinned its faith on the Western Front on the Siegfried Stellung, called the ‘Hindenburg Line’ by the Allies. This was a purpose-made line of state-of-the-art fortifications, constructed in 1916-17 to act as a final backstop, a ne plus ultra of their defences. By the end of September the Germans had been forced to retreat back to this line, but they were confident they could hold it there. They were wrong. An attack on 29 September by British and Australian troops broke through the Hindenburg line at its strongest point, the St Quentin Canal. As at Amiens the previous month, thousands of German troops surrendered rather than fight to the finish.

It would take until November for Germany to admit, that there were simply no more young German men the nation was willing to sacrifice.

As Hillary Spurling explained in Matisse the Master: A Life of Henri Matisse, the Conquest of Colour, 1909-1954, when the War finally ended and the British finally liberated Bohain, the brave mother proved to be a hardy survivor. She hid her treasures, endured German requisitions and looting and sold her piano for food, but she had survived. The War was over, the survivors united. Although he would live in Nice the rest of his life, Matisse would a celebratory Paris to find himself, along with his friend Picasso, an old master, established and secure in his new direction.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.