Georges Braque Post-War

Return to Cubism

The question both during and after the Great War was the fate of Cubism. The forward thrust of the pre-war avant-garde in Paris was abruptly halted by what Barbara Tuchman called “The Guns of August.” Conflict and disruption are never helpful to artists who need peace and prosperity to contemplate their art, find collectors and make a living. The War, however, divided the leading pre-war movement, Cubism, in half: the Cubism before the War and the Cubism after the War. After the War Cubism acquired a totally different character, evolving from an armed rebellion assaulting the sensibilities of the public to a historical movement supported by a new generation of art dealers with respectable clientele. Before the War, Cubism, as a movement, had been divided into two different intellectual concepts, two separate aesthetic visions, one public, the colorful and, according to some, conservative, Salon Cubism, and the other private and studio based, the experimental projects of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Although both strands of Cubism could be traced back to Paul Cézanne, it was the Salon Cubists who emerged as the main “Cubists” after the War. Art history tends to neglect the Salon Cubists, such as Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes, and also has the habit of skipping over the way in which Cubism was established as a major force in the art market by these Salon Cubists after the War. In contrast to the Salon Cubists, after expanding its possibilities for his ballet designs with Parade, Picasso abandoned Cubism in a bid for wider acceptance. While Picasso developed a strategy to build his reputation as an ever-flowing artist, moving with each tide, each style and mastering it before moving on, his former partner, Georges Braque took a different road.

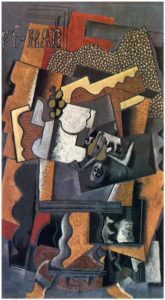

Braque, who had been wounded during the War, had almost died but struggled to recover and return to painting. Although Picasso had been solicitous and had visited him in the hospital during his rehabilitation, Braque became aware that their paths had diverged during the War, and, as he contemplated his comeback as an artist, he apparently made the decision to continue develop Cubism. Part of Braque’s transition out of the army and back into painting were two celebratory events, one to honor the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who seemed to have narrowly escaped death, and then a party honoring the painter, also recovering from a head wound and wondering if he would ever paint again. These parties in 1917, marking survival, marked the return of two prominent figures to the art world in the same year as Picasso’s Parade debuted. Picasso’s use of Cubist painting as costumes and sets in this “surreal” ballet were his swan song, his farewell to the style that made his reputation. For him, Cubism provided a way out, an exit to new artistic frontiers. For Braque pre-war Cubism beckoned to him as a way forward. As with Picasso’s work on Parade, Braque’s post-war paintings bear the memory of papier collé, with areas of strong color that were painted instead of large blocks of pasted paper. And, as with Picasso, these paintings use the old subject matter of Analytic Cubism and its characteristic sharp diagonal likes which now emphasize the shapes of the objects rather than fragmenting them. Rather than floating above the support, the segments of color build upon each other, locking each other down.

Georges Braque. Glass, Pipe, Newspaper (1917)

Interestingly Braque relied upon the audience’s ability to “read” the “clues” of Cubism, a skill that had been developed before the War and not necessarily in Paris. What the potential Parisian collectors could see, however, is a style called “Cubism” as interpreted by its inventor, Georges Braque. As several of his transitions works made during 1917 and 1918 demonstrate, the artist relied heavily upon the papier collé works he was doing at the end of the summer of 1914, especially those which introduced a textured surface.

Georges Braque. Rum and Guitar (1918)

Perhaps, however, when it comes to the choice of color, a more informative comparison of Braque’s paintings he made during his recuperation would be with Henri Matisse, for, like the former Fauve with whom he once exhibited, Braque went dark. In comparison to the monochrome paintings of the so called “Analytic” stage, these paintings are dark and brooding. In comparison with the open structure of the floating segments of “Synthetic” Cubism, the canvases are filled and closed in. Braque also announced, if you will, the new work with a new motif that would appear for decades in his work, the Guéridon, a small side table dating back to the era of Louis XIV. The top is round, a site where Braque would crowded bits a pieces familiar to those who knew his early studies–musical instruments, sheet music, newspapers, things to eat and drink, all the comforts of home. The Guéridon had made an early appearance in 1910 and then in 1911, with its characteristic curved top was clearly visible as an edge barely supporting a plethora of disintegrating objects.

Georges Braque. Le Guéridon (1911)

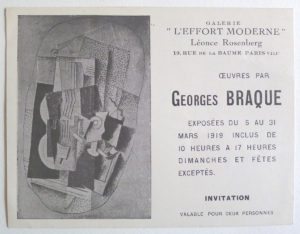

The side table still life paintings would be the center of Braque’s comeback in 1919 at Léonce Rosenberg’s gallery L’Effort moderne, but they were also his version of continuing to develop Cubism. Picasso abandoned Cubism during the post-war years and wandered off, exploring new styles, slipping from one look to another, as if traveling. Once settled in his darkened and sober color scheme, blacks and greens and browns, once he had returned to the comfort of still life motifs, Braque settled back into his own trajectory and stuck with his darkened Cubist perspective. It is possible to read the deep tones as elegiac for all that was wiped away by the War–human lives ended, an entire world of international avant-garde art halted, the nineteenth century itself–for a new century was well and truly underway.

Georges Braque. Guitar and Glass (1917)

However, unlike Fernand Léger, Braque did not let his experience as a machine gunner penetrate into his art. Instead, his art was about being back home, at home, safe in a charmingly cluttered interior, surrounded by timeless and familiar objects. The three legged table symbolized peace and safety. Although Braque returned to the familiar stacking technique of Cubism, in which space was flattened by the tilting forward of the objects which offered themselves to the viewer, the confrontation with building blocks of color and pattern might take on a different significance post-war, becoming signifiers of an urge to recommit to all things familiar and insignificant and close to hand. In a very interesting article, ‘Trench Warfare on the Western Front, 1914-18,” Dorothee Brantz wrote of the odd vantage points and the unusual experiences with space and landscape for those, who, like Braque, lived in trenches:

Trench warfare forced soldiers to develop a new relationship with space, including intensified sense perceptions. To some soldiers, going to war, might initially have looked like an adventure, but they quickly realized the life at the front was nothing like tourism. For one thing, there was little to see. Trench warfare no longer privileged sight,particularly when it came to locating the enemy. Not only was the landscaper increasingly unrecognizable due to military destruction, most soldiers spent large amounts of time close to or even below ground, where their field of vision was limited to the boundaries of the trenches, creating a particular perspective. As a result, battlefields looked empty even thought they were actually saturated with bodies, both living and dead. Even inside the trenches, soldiers often could not see very far because of the trenches’ zig-zag construction. The view across no-man’s land was obstructed by barbed wire and upturned earth, and during a barrage this field of vision was even future reduced with smoke or poison gas filled the air.

This landscape had been were Georges Braque had spent almost two years of his life. It is no wonder that he surrounded himself, wrapped himself in traditional still lives, places at a distance where he could see them, study them, and revel in their simple existence. In contrast to the semiotic fragments of early Cubism that provided a narration of a visit to a café, for example, the post-war still lives are rendered in full, redolent with decorative, celebratory details. The verticality now takes on a different connotation when contrasted to the dangerous flatness of a non-landscape stripped of all identifying markers but dead bodies and barbed wire. The new distance, allowing for a full view of a still life on a graceful table or even including the table itself, allows for a verticality, indeed, even the possibility of the act of standing upright-a posture that would mean instant death for the inexperienced soldier.

Georges Braque. Still Life on a Table (1918)

Having survived when so many did not, Braque, according to Alex Danchev, regarded his former confrères who did not serve, such as Marcel Duchamp, or who managed to cut their service short, such as Albert Gleizes, with a certain contempt. Picasso, in his opinion, simply sold out and of his post war life, Braque said, “Je dos connaître ce monsieur.” The paintings of Braque demonstrated how cleanly the artistic break with Picasso had been: Picasso became a celebrity, Braque remained the historical champion of Cubism and its future; Picasso frolicked on the Cote d’Azur with movie stars and prominent members of the rich and famous class, Braque stayed at home and painted objects arranged and rearranged over the decades. Early on, as with Musician, his 1917 return to painting, and La Joueuse de mandolin of the same year, Braque insisted on continuity and these paintings, like the Guéridon, had previous versions in his former life.

Georges Braque. Musician (1917)

Georges Braque. La Joueuse de mandoline (1917)

Braque’s return to public exhibition at L’Effort moderne in 1919 and the review of his new work was penned by Blaise Cendres whose right arm had been amputated. Centers, a Swiss national, had served in the French Foreign and Cendres (Frédéric–Louis Sauser), like Braque, was recovering from his wartime experiences, as were Luigi Russolo, who also had a head wound that was trepanned, and Fernand Léger, who had been gassed. Raymond Duchamp-Villon died in the service of his country. It is in the face of the sacrifices of the avant-garde artists during the Great War that Cubism, once spelled “Kubism” with a “K” to damn it in its supposed German-ness, that Cubism finally became French, part of the French tradition. Braque chose to remain within this continuity, established by Léonce Rosenberg who was both taking advantage of the Cubist artists and promoting their art for mutual benefit.

In A Companion to World War I, John House quoted Fernand Léger, who said, “To all those idiots who wonder if I am a or will still be a Cubist when I return, you can tell them that, yes, for more than ever. There is nothing more ‘Cubist’ than a war like this one which splits a chap up more or less cleanly into several bits and flings him out to the the four points of the compass.” But how should we read these key transitional works from Georges Braque, a recovering veteran of a war he would seldom mention and seemed to repress? One hundred years after Braque was called into service, Karen K. Butler wrote of “Georges Braque. Artilleryman” in Nothing but the Clouds Unchanged. As she pointed out the working process of Braque was largely “internal” and that his philosophy of art was to divorce his work from the real world. In writing of his experience with trench warfare, Butler commented, upon a statement by Braque:

“Visual space separates objects form one another. Tactile space separates us from the objects. VS (visual space): the tourist looks at the site. TS (tactile space): the artilleryman hits the target..It is my position the some of the irreconcilable aspects of Braque’s war experience that are found in this statement–a kind of perceptual gap between distance and presence, as well as an emphasis on tactility and physical experience before the mechanization war–find a way into his post-war paintings.

Georges Braque. Still Life on Table (1918)

Butler concluded,

..it is difficult to connect these still lifes and interiors in any overt way wot the war. And yet it is worth considering whether the serial nature of these canvases ,which return again and again to the same motif with only slight variations in subject or perspective, is in some way suggestive of a psychological response to trauma–a response that is both a repression of the experience of war and an unconscious reiteration of its tactile space. For Braque, who, strives to hit his target like the artilleryman, I propose that his emphasis on the material qualities of the artwork is deeply tied to the devastating encounter with industrialized mass destruction that emerged in the trench warfare of World War I.

In 1996 the historian and art historian Philippe Dragen wrote Le silence des peintres: les artistes face à la Grande Guerre, taking an interesting stance, particularly when it comes to the French avant-garde artists. While the English artists rose to the occasion, looked the war directly into the eye of this first modern war and created, out of the avant-garde vocabulary, a language to express the death and devastation, the destruction of an entire swarth of landscape and the desolation that followed the loss of a generation upon which the future had once depended, the French artists looked away. As will be discussed in the next post, the vast bulk of French art was prints and posters, with almost none of the major pre-war artists approaching the war in any fashion expect indirectly at best. It is difficult to account for such a vast difference–eloquence on one hand and repression on the other, but it should be remembered during the first month of the War, France was delivered a death blow which was still bleeding in 1940, when on a fine day in June, the Germans once again marched down the Champs Elysees.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.