Modernity and Military Painting

François Flameng

It is one of the ironies of the first modern war that the oldest of artists painted the newest of things–the first airplanes that flew combat missions in the Great War. French academic artist François Flameng (1856-1923) produced one of the most extensive visual accounts of the first modern conflict, and yet art history has passed this artist by. There is very little research done on this artist, who, in his own time, was famous and well respected; but historically, the academic artist was a casualty of changing tastes for art and new expectations of audiences. However, Flameng died at the peak of his reputation and would not know that his very real accomplishments during the War would be slighted. Indeed a French source noted the immediacy of his obscurity by stating, “Rares sont les artistes à avoir été aussi connus en leur temps, et aussi oubliés par la suite, que François Flameng.” Flameng, who had been a young man and marked by the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, studied under Alexandre Cabanal, a leading academic artist and became a history painter, best known for his military themes. For the bulk of his career, with the exception of portraiture, the artist lived in the past. Flameng was the Meissonier of his day, celebrating the heritage of Napoléon I in particular, reliving the glory of the era when France dominated Europe.

Edmond Bénard. François Flameng (1880-90)

And then, when he was in his sixties, this mature artist was suddenly thrust into the twentieth century when the Great War ended his extended dream of Napoleonic drama and valor on the battlefields. Flameng rose to the occasion and visited battles without valor and recorded the rise of an entirely new branch of the French military, the Aéronautique Militaire, depicted the frightening gas masks worn by soldiers, watched the new tanks roll across the battlefields. At the same time, he watched the modern soldier slogging across the muddied fields of Verdun and the Somme, and watched battles shorn of anything glorious or exciting. As a witness to the twentieth century, François Flameng was confronted with a reality he was expected to record and report back to a curious and anxious French public.

The change in the artist’s approach to military painting could not have been more extreme, and, indeed, in the career of this one artist, Flameng, it is possible to watch the death of the traditional depictions of war inherited from the nineteenth century and the struggle artists had with showing the truth of a modern war. Flameng grew up doing those decades after the 1870s, while the French were dreaming of revanche or revenge against the German invasion and occupation of their soil. Somehow, the French narrative of the Franco-Prussian War elided the inconvenient fact that the French began the war and moved directly to the humiliating defeat at the hands of their foes, that must be answered in the future. Although some academic artists, such as Detaille, as was discussed in earlier posts, were able to find small incidents of valor in defeat during the humiliating war, other artists, Flameng being one of them, reached further back in time to the glorious days of Napoléon I. Under Napoléon, France experienced victory after victory, dominating Europe, just as Great Britain dominated the seas. Flameng shows the heroic aspects of Napoleonic rule, from the brilliant red uniforms, the glittering gold braids, and the celebratory mood under the young Emperor. Josephine’s Château de Malmaison is shown as a place of carefree and fashionable family life in the halcyon days before her husband’s ambitions cast the army and the country into chaos. Flameng did not shirk from painting the Emperor in defeat, pondering his fate after the decisive Battle of Waterloo. For the public who came to the academic salons, such history paintings were like visual textbooks told from the French perspective of nostalgia for victories. When Flameng was reaching his peak in his career as an artist of the past, the romance for the old century was a symptom of an underlying sense that modernity was intruding and demanding that the national mentality about war needed to get in step with the progress proffered by the twentieth century.

François Flameng. Napoleon and his staff reviewing the mounted chasseurs of the Imperial Guard before the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel (1901)

François Flameng. Reception at Malmaison in 1802 (1892)

François Flameng. Napoléon at Waterloo (date unknown)

Nothing could be more different from the Napoleonic Wars, wars that consumed the first two decades of the nineteenth century, than the Great War in its dour colorlessness, its lack of adventure and glory, than its suffering condition as a lingering bloodbath. In contrast to the antique settings of the early nineteenth century which stressed the combatants rather than weapons, the paintings Flameng made of the four year war chronicled the new weaponry, brought forward by the increasingly urgent desire to break the stalemate on the Front. The military, perhaps remembering Napoléon’s genius with artillery, assumed that the big guns, which could fire over long distances, would solve the problem of the immobilized armies by pulverizing the German lines. However, the big guns, on both sides, did as much damage to the landscape as they did to human beings, with little result for the massive amount of shells fired and the extreme destruction they wrought–destruction that is still unhealed today. The guns fired but the soldiers used the trenches wisely in order to survive.

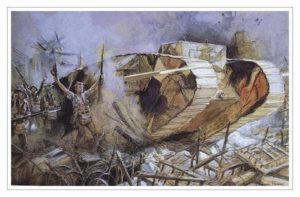

François Flameng. Batterie 400

Tanks were another new invention, a British innovation, designed to end what had become a battle of mutual annihilation and bring the War to a decisive end. Since the fall of 1914, the Germans had been dug into defensive trenches that cut into Belgium and French territories, leaving the onus upon those nations to attempt to push the Germans back and out of their homelands. But nineteenth century battle tactics, artillery bombardment, followed by infantry advance, resulted in high casualties and, no matter how many times, the time honored strategy was tried, it failed. Even poison gas and flamethrowers, horrific weapons, did little to change the stalemate created by trench warfare. Previously, trenches had been dug prior to and in preparation for siege warfare, but with the Great War, the zig-zag ditches became the defining feature of the Western Front and the Eastern Front. The plan then became to see which nation could kill the most young men–there seemed no other way out. There were two decisive moves that finally ended the War, without changing the status quo. First, was the arrival of the Americans in 1917. Badly trained and ill-equipped to be sure, but there were many, many Americans, an inexhaustible supply, compared to the depleted German generation, spelled an end to the Kaiser’s hopes of victory. The second change, also debuted in 1917 was the new tactic of using the tank to push into no-man’s land ant to break through barbed wire and, with the infantry following closely behind, taking the German trenches. The first major battle in which the tank, a lumbering beast of an armored vehicle, played a decisive role was a British offensive at the Battle of Cambria between November 20 and December 8th. At first the British advanced, surprising the Germans and forcing them to retreat but the Germans counterattacked before the Army could fortify and solidify its initial gains. Flameng’s depiction of a tank shows what a tank could do–crush everything in its path–but is rather bloodless, compared to Muirhead Bone’s powerful drawing, which positioned the viewer in the frightening position of being under a tank which is rearing up, poised to pounce.

François Flameng. This is a painting of a British Mk 1, sporting 1916-camouflage, and followed by cheering infantry; surely an attempt to recreate the Tanks debut on the Somme, and the taking of Flers: “A tank is walking up the High Street at Flers, with the British Army cheering behind.”

It is difficult, from the vantage point of a century later, to grasp just how primitive the machines of the first modern war really were. Airplane pilots had no seatbelt and the seat was so shallow that there was no room for a parachute. Tanks did not have rotating turrets until the French tank, the Renault FT combined the rotation from an earlier model with Faible Tonnage or low weight. In contrast to the heavier tanks of the past, this 1917 model was nimble and lightweight and could attack in numbers as opposed to intimidating by size. The “female” version was armed with a machine gun, and the “male” model had a howitzer. By the war’s end, Renault had produced almost two thousand tanks, an extraordinary accomplishment.

If one compares Flameng’s military paintings set in Napoleonic times with his work during the Great War, it is clear that he considered himself as an illustrator. There is little in his work that goes beyond the mechanical reportage. This distanced approach is odd, considering Flameng’s imaginative take on life during the nineteenth century, a history he did not witness. Confronted with a genuine history, the artist wrung pathos and empathy from the sights he observed, as if by eliminating feeling he could present the view with a dry dissected version of a painful war. Flameng always kept his distance. Comparing his watercolor of the dead, sprawled near a barrier of barbed wire with those of Nevinson or Orpen, discussed in earlier posts, the emotional divide is clear.

François Flameng. Prise du Plateau de Californie. Chemin des Dames, Aisne, 15 mai 1917 (1917)

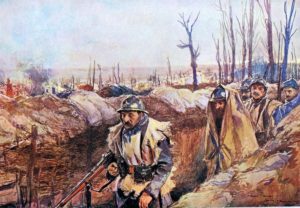

And yet, there is something to gain from this comprehensive view of a war and its many battles. Flameng shows a war that is impersonal, death is done at a safe distance for some, and for those for whom death comes hand to hand, face to face, their demise is not individual, merely numerical. His studies of soldiers in groups has the same frozen look of alienation, one of the major themes of this War. One of the new rules of this War with such high casualties is to not get close to the men with whom you serve for any friend is likely to be dead the next day. This cool tone from Flameng, buttressed by the colors he selected for this bleak conflict, may have been necessary, considering that by the end of 1915, France had lost two million soldiers, half of whom where dead–a million dead in one year. The nation was literally on its knees, broken but unbowed, and not allowed to weep.

François Flameng. Near Peronne, 1916 (1916)

In his previous works set in the nineteenth century, Flameng tended to concentrate on the leaders or officers, but for this very new war, it was the common soldier who captured the country’s attention and sympathy. The humble infantry, the pioupiou, mired in the trenches, trudging wearily towards almost certain death, became the symbol of the futility of the War, the cry of which was attaque à outrance. Only the airplane, a relatively new invention, a mere decade old, offered escape from the mud and an opportunity for personal glory. Interestingly, after making a career celebrating military drama, Flameng divided his attention evenly, showing men below the ground and the magnificent airplanes, built by French technology, which soared high above the earth.

François Flameng. Artois, 18 décembre 1915 (1915)

The French Air Service is considered the world’s oldest air force, but very little writing on the topic of this air force, to use American terms, has been either done in English or has been translated into English. Even one hundred years later, it is difficult to find an objective account of its history. As Alphonse Nicot wrote in 2015,

L’aéronatique pst une science entierement français; c’est en Allemagne, grâce à l’effort persévérant des pouvoirs public, due l’aétonautique militaire a trouvé son plus grand development..L’aviation, elle aussi, pst uno science français. Ses débuts, ses progress not en lieu en France, et ce sont des aviators français qui établirent tour les “records du monde..” De sort due l’aviation, créée en France par la génie français, fut surtout utilisée par les Allemands au point de vue des applications à la guerre moderne.

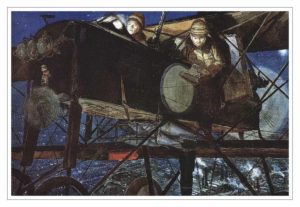

Nicot’s writing indicates a lingering enmity towards the Germans and an insistence upon the primacy of the French “genius” in aeronautical sciences. It would be pointless to note the accomplishments of the Wright Brothers in America, because it was indeed the French who realized the military possibilities the air plane as early as 1910 when the Aéronautique Militaire was set up under the French Army, where it would be ‘housed” until 1934. When the War broke out, the French were ready with twenty one squadrons or escadrilles. However, the first uses of the airplane at the beginning of he War was largely for reconnaissance. Pilots, sometimes accompanied by another crew member, would fly over the trenches and photograph the landscape below. One of those pilots was a young German named Herman Goring.

As Spencer Tucker pointed out in his book The Great War, 1914-1918, “The most important aircraft of the First World War were two-seaters used for reconnaissance, aerial photography, and artillery observations..Control of the air over the battlefield soon became vital, with most aerial combat occurring over or near the trench lines where the bulk of reconnaissance and spotting took place.” At first, pilots on opposing sides merely waved at each other in passing but then, the significance of the aerial photographs became clear, they began to shoot at each other with side arms or rifles. Fighter planes, designed with the idea of protecting the reconnaissance operations, did not emerge until 1915. Bombing, however, began in 1914. In his essay, “The First Air War Against Noncombatants. Strategic Bombing of German Cities in World War II,” Christian Geinitz wrote,

At the beginning of the war Britain’s ally, France, possessed the most modern military planes in the world. With them the French sought to spot the mobilization of German troops while they were still on German soil. Haphazard strikes against points of German mobilization gave way in the autumn of 1914 to a strategic concept of bombing military targets and the infrastructure of the German war economy..the first strategic bombing squad, the “Groupe de bombardement Numero 1,” formed in Belfort.

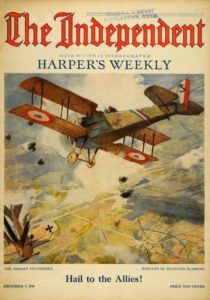

Despite the premier position of France in developing air craft and tactics and strategies for aerial warfare, it was not until 2007 that René Martel’s 1939 account of L’Aviation Française de Bombardement (Des Origines au 11 November 1918), a history of aerial bombing was translated into English. Although strategic bombing would have long reaching and controversial consequences, public fascination, then as now, fixated on the fighter planes and the dashing pilots, the Knights of the Air. As Tucker noted,

..the best way to shoot down enemy aircraft was to arm one’s own planes..In April 1915 Frenchman Roland Garros, a stunt pilot before the war, mounted an automatic rifle on the hood of his monoplane and installed a primitive synchronizer gear designed by Raymond Saulnier that allowed bullets to pass safely through the plane’s propeller. Because the device was imperfect, Garros also fitted the propeller with metal cuffs to deflect stray bullets that might hit the blades. Although crude, the process was effective and over the next several weeks Garros shot down several enemy planes before he was shot down by anti-aircraft fire during a bombing run on a German train. Dutch aircraft designer Anthony Fokker, working for the Germans, took it a step farther. He developed a truly effective cam-operated synchronizer that allowed bullets to miss the propeller altogether. He combined his synchronizer with the Spandau or Parabellum machine gun mounted on an Eidecker. In August 191 there began an eight-month period known as the ‘Fokker Scourge,’ when the Germans dominated the skies over the Western Front before the Allies developed their own effective synchronizer gear.

François Flameng. Magazine Cover

The two sides were locked into a race for the most lethal technology. The airplane was but one weapon the combatants had to learn how to develop as a machine in its own right and how to deploy the new apparatus for War. This history of the airplane–on both sides–is instructive because the story that is told is one of learning on the job, how to build the craft–monoplane, or biplane or triplane–how to mount the engine–back or front–how many seats–one or two–how to fly–in a straight line or in circles or in curves–all of these interlocking elements had to be worked out independently and together. And yet the myth of the fighter pilots captured the imagination of the public. Writing about the Americans who served with the French during the War, Kyle Nellesen discussed this glamorization of the air war:

Fighter pilots took to the skies alone in their planes, engaging the enemy in combat which would end with one’s death. The image created around these men was essentially a revival of the warriors of antiquity. The ideals of chivalry and gallantry were manifested in the public’s view of the “knights of the air.” The elevation of the aviator as a hero comes largely from the nature of the ground fighting during the war..From the very beginnings of air combat, fighter pilots were seen as heroic figures.

François Flameng. Combat aerien’ L’avion ennemi s’abattant en flammes (1918)

The Germans were the first to celebrate their pilots. Kaiser Wilhelm personally awarded the Pour Le Merite, or “Blue Max,” to pilots Oswald Boelcke and Max Immelmann in January 1916. The award was the highest military honor of the Prussian kingdom, and from this point on it was almost exclusively awarded to high-scoring German pilots. Consequently, fighter pilots became extremely popular in Germany, even appearing on collectible cards. The French government followed suit by mentioning successful pilots in nationwide press releases. The term “ace” comes from the French, as they would refer to pilots with five or more victories as “the ace of our aviation” (“l’as de notre aviation“). The press attention garnered by pilots had an enormous effect on popular opinion, and the public invested their new-found heroes with the same qualities as the heroes of old.

François Flameng. Champ d’aviation, février 1918 (1918)

Interestingly, Flameng’s view of the air force in which the Allies flew a variety of planes shows a more pedestrian standpoint. His view, again, is not about the pilots but about the aircraft themselves as major actors in the War. His role as an artist in this war was, first of all “official,” in that he was acting for the French government and second, he was working within a mode of distribution that was based upon prints, not paintings that would be shown at exhibitions.

François Flameng. La Grande Guerre. Vue par les poilus

The fact that the audience for Flameng was the general French public no doubt explains his sanguine matter of fact approach. As honorary President of the Société des peintres militaries français, his art is important because each work is a carefully researched and observed historical document. One learns from viewing a reproduced work by Flameng–one learns about the patriotism of the soldiers, not their spirt or their élan, but that which gave them to the will to continue fighting, the sense of duty that it is right to die for one’s country.

François Flameng. Le défilé de la Victoire, le 14 juillet 1919 (1919)

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.