Dada Émigrés in Exile

The Disintegration of Kultur, Part Two

Today the city is called Leuven but one hundred years ago, the university town was called “Louvain,” and it was the site of an atrocity, a war crime against property, against culture, against human beings that attracted international attention. On August 25, on its way to France, the German army angered and delayed by the defiant troops of Belgium, took out its rising wrath on an innocent civilian population, composed of professors and towns people standing between Liege and Brussels, in the way of the imperial progression to victory. In Dynamic of Destruction: Culture and Mass Killing in the First World War, Alan Kramer described the march of Germany through a neutral nation:

The German troops arrived in the town in the morning of Wednesday, 19 August, to find a peaceful population frightened by the news of German cruelties perpetrated along their invasion route since 4 August. In the area around Liège, closest to the German border, some 640 civilians had been killed by 12 August, but no precise numbers were known at the time. The town of Aarschot, only some ten miles north-east of Louvain, was the scene of mass killings on 19 August, with 156 dead; in Ardenne, further south, 262 were killed the next day. The Louvain civic authorities had confiscated all weapons in private hands in early August, to prevent any spontaneous individual acts of resistance the might provoke reprisal, and published warnings that only one regular army was entitled to take military action.

Propaganda Poster

Louvain had heard of how Germans had treated other cities and had subdued themselves accordingly while the army marched in and the German military itself considered the town sufficiently secure to make it the headquarters of the 1st Army. But something spooked the occupying army on the evening of the 25th sending the German soldiers into a frenzy of of wrath and retribution, seeking mythical French “franc-tireurs” of free shooters, civilian snipers encountered during the Franco-Prussian War, resurrected in Belgium. While assaulting the civilian population, executing and torturing townspeople, setting their houses on fire, damaging a fifteenth century Collegiate Church of Saint Peter in the process. The famed University Library was singled out for special treatment. As Kramer wrote,

Using petrol and inflammable pastilles, they set it on fire. The library burned for several days, but within ten hours, little remained of the building and its collections apart from blackened walls, stone columns, and the glowing embers of books..the killings continued the next day and night, Wednesday 26 August..In all, 248 citizens of Loubain were killed. Some 1,500 inhabitants were deported to Germany on a long journey in railway cattle-wagons, including 100 women and children and were forced to endure the harsh conditions in Munster came until January 1915.. Still the misery was not over. On Thursday, 27 August the German army announced that the town was to be bombarded, because its citizens were allegedly firing at the troops..Most of the destruction had been caused by arson.In a town of 8,928 houses, 1,120 were destroyed, including some of the wealthiest properties, in addition many public buildings and commercial premises. Not only university library and archive also the personal libraries, research papers and professional documents of five notaries, 14 solicitors, 5 judges, 15 medical doctors, and 19 professors were lost..witnesses testified to pillage on a large scale.

The University Library, Louvain

The town of Louvain was thoroughly sacked. The British press sprang into action. As Troy R. E. Paddock explained in his book A Call to Arms: Propaganda, Public Opinion, and Newspapers in the Great War, what we would consider war crimes today were so novel a hundred years ago that they were hard for the public to believe. Reporters were caution in their account, apparently concerned they would not be believed. Nevertheless from the early weeks of the war, a steady flow of accounts of German “misbehavior” appeared in English and French newspapers. And each atrocity report was countered by the Germans with charges of lies by the enemy and by counter narratives that were falsehoods aimed at neutral nations and at the German public. In the Daily Mail, a journalist Hamilton Fyfe used the terms “Barbarity” and “Sins Against Civilization” and “savage” and “uncivilized” and “barbarous,” terms that had a tendency to sensationalize accounts that were utterly truthful. In the growing accounts of “atrocity propaganda,” Louvain, as the author reported

was significant for two reasons. The first was its particular cultural resonances..Louvain was an undoubted cultural jewel, a perfect site for proposing a powerful thesis that the German army was a real enemy of civilization. The second was that after the German army committed its crime, the town was briefly recaptured, giving a rare opportunity to verify what had occurred..The relative caution of earlier editorializing is being replaced by a certainty of German bestiality. Louvain seems to be a turning point..It seems likely that it was the combination of verifiability and visual impact that made this particular town so important. The physical destruction visited on Louvain was massively emphasized during the final week of September with photographs at the back of the newspaper..It is in this context that the initial use of the word Hun in the Daily Mail needs to be understood. Rudyard Kipling’s poem, “For All We Have and Are”had used the line “The Hun is at the gate,” and its first use in the Daily Mail is a direct echo of this, immediately after the news of Louvain..The use of Hun began to emerge in this very specific context, that of an assault on the physical manifestations of civilization..this was the worst act of cultural destruction in more than a century, involving a university town the equal of Oxford or Heidelburg. For this reason Louvain has been described as the Sarajevo of the European intelligentsia, leading to a widely reprinted exchange between British and German academics.

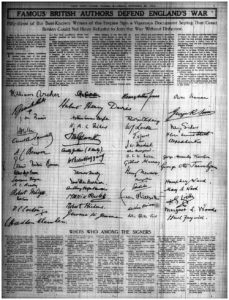

The first salvo was delivered by the artists mobilized by the well-organized arm of British propaganda, Wellington House, in the form of an “Authors’ Declaration” in September 1914. The fifty-three signatories noted that

We observe that various German apologists, official and semi-official, admit that their country had been false to its pledged word, and dwell almost with pride on the ‘frightfulness’ of the examples by which it has sought to spread terror in Belgium, but they excuse all these proceedings by a strange and novel plea. German culture and civilization are so superior to those of other nations that all steps taken to assert them are more than justified, and the destiny of Germany to be the dominating force in Europe and the world is so manifest that ordinary rules of morality do not hold in her case, but actions are good or bad simply as they help or hinder the accomplishment of that destiny.

Signatures of British Authors

In response to the denunciation of German “barbarism” in the name of Kultur, ninety-three German intellectuals and artists published the “Manifesto of the Ninety-Three” but first appeared as “Aufruf die Kulturwelt!” a deliberate word choice, no doubt, in all German newspapers. Written in probable good faith, patriotism and complete ignorance of the actual events, the document declared,

It is not true that our troops treated Louvain brutally. Furious inhabitants having treacherously fallen upon them in their quarters, our troops with aching hearts were obliged to fire a part of the town as a punishment. The greatest part of Louvain has been preserved. The famous Town Hall stands quite intact; for at great self-sacrifice our soldiers saved it from destruction by the flames. Every German would of course greatly regret if in the course of this terrible war any works of art should already have been destroyed or be destroyed at some future time, but inasmuch as in our great love for art we cannot be surpassed by any other nation, in the same degree we must decidedly refuse to buy a German defeat at the cost of saving a work of art.”

Historian Stefan Wolff pointed out that the manifesto, translated into ten languages and distributed to neutral nations, was a complete failure and that physicist Wilhelm Wien attempted to provide “the facts in the way he believed to know them” and, disbelieving all accusations against the German military,” writing “None of the accusations our enemies are spreading against us are true.” A month later in November 1914, Thomas Mann, author of Buddenbrooks, published “Gedankem im Kriege” in Neue Rundschau. As Mann pointed out in a letter to Richard Dehmel in December 14, 1914, many manifestos had appeared in Germany defending Kulutr and denying the reports of destruction of cultural monuments and property, and he wrote, “Not that I deluded myself that writing it was any special achievement. I am not one of those who think that the German intelligentsia “failed” in the face of events. On the contrary, it seems to me that some extremely important work is being done in spelling out, ennobling, and giving meaning to events, and I feared that my little piece of journalism would make a miserable showing alongside these other things..” Several important points need to be made: first the German scientists and artists and intellectuals were, with few exceptions, united in their support of Kultur and therefore were defending their nation’s innocence and, sadly, bound together in their completely unquestioned belief in the deliberate lies of their own government, distributed through mass media. Mann, himself, renounced his early naïve patriotism, but not until 1918. The blindness to German behavior during the first months of the War was not universal and surely led to the recoil felt on the part of thoughtful people, from Albert Einstein to the artists who withdrew from the conflict.

Louvain in 1915

Before the year 1914 was finished, the German military committee and denied war crimes, and the intellectuals of Germany were misled into defending the destruction of cultural property of the enemy, opening themselves to the charge of religious bigotry–Protestants attacking Catholic heritage and sites of learning. In “Kultur and Zivilization,” on the the best extended discussions of the origin and meaning of German Kultur, Arnold Labrie discussed the origin of the dichotomy between German Kultur and French Zivilization in 1784 with Emmanuel Kant, in which “Kultur results from an inner moral necessity; the truly cultivated person behaves in a civilized way, because he can not do otherwise. As Labrie stated, “This negative association between Zivilization and bourgeois society was to become an important part of German ideology, culminating during the First World War..” In order to understand the impact of the disgrace of Kultur it is important to understand to the extent to which Kultur was the “possession” of the class of people represented by the Dada artists who fled to Zürich. Labrie continued,

To a certain extent, this idealized vision of Kultur reflects the social position of the literary elite, the so-called Bildungsbürgertum, which more or less consists of people working in the liberal professions or other positions requiring higher forms of education (gymnasium and university). The Bildungbürgertum may be considered the social group supporting the German idea of Kultur.” According to the author, this class understood the Franco-Prussian war to be one of Kultur against Zivilization. “The same attitude was to return during the First World War,wen almost every intellectual considered it his patriotic duty to contribute to the ideological battle against Western Civilization by writing pamphlets and articles. In 1915, for instance, the prominent sociologist Werner Sombart published his book Helden und Händler. The heroes of this story are German soldiers, dying for the cause of Kultur, which now has found its political expression in the state. These German idealists are opposed against Western merchants, Händler, who was strictly interested in material profit..To a certain extent, Buildung and Kultur served as a surrogate religion which filled the spiritual void that was left when orthodox christianity gradually lost its hold on the literary elite during the nineteenth century..Kultur..originates in religious cultus and it this way refers to eternal, inner values of the individuals’s faith or Weltanschauung..

By the time the Dada artists and writers had arrived in Zürich and gathered together for comfort in the Cabaret Voltaire, German Kultur was under fire, German soldiers were considered “barbarians” and commonly called “Huns,” and in 1916, Germans were convicted of war crimes in the minds of everyone but the German people themselves. The visual and verbal propaganda from the British and French and Americans were both merciless and exaggerated, playing on fears and arousing hatred against the now “frightful” enemy. For an intelligent outsider, who could see the photographs of the smoldering ruins of the university library of Louvain and the bombarded ramparts of the Cathedral of Rheims, Germany stood tried and convicted of the destruction of cultural property, the desecration of literary documents and a lack of reverence for history itself. In addition, norms of civilized behavior, which were universally recognized, had been smashed and left behind in the dust and hysteria of total modern war. Kultur, an entire way of life which had, for two hundred years, had formed the basis for the inner life and for the intellectual raison d’être for an entire class in Germany, was no longer tenable. For any artist, writer or intellectual, especially those of German heritage, the choices were complex: one could defend the indefensible, as Thomas Mann did, or one could take the more difficult path–find a new way to create a new form of culture without the blinding idealism of the past. The Dada artists were of the class of people charged with creating and contributing to Kultur but they had lost Kultur and needed to make statements about their willingness to destroy Kultur the way that Kultur had destroyed Louvain.

The next posts will discuss the visual propaganda that depicted the German people, establishing an image that would lead to the humiliating Treaty of Versailles in 1919. The negative representation of the German people and of German Kultur was part of the back story of Dada, an important component of the anger of the artists against the War and its consequences.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.