British Propaganda

The Psychology of Posters

When the Great War began in August of 1914, Great Britain was at a distinct disadvantage. Although it was expected that Germany would be aggressive at some point, this was not a war the English wanted. The British Isles were not a military society and the monarchy was not surrounded by a martial presence of sword rattling. Regardless of their individual capabilities, the guards at Buckingham Palace were ceremonial in appearance, appearing publicly in splendid uniforms that dazzled the eye. But behind the diplomacy and the ceremony was a vast Empire that was offshore, so to speak, supported by an extensive professional army stationed in more or less remote outposts, from India to China. The Empire was patrolled by the equally professional Navy, the most powerful in the world, guarding the vast territories that were the foundation of England’s wealth and power. The most dominant Empire, the most important nation on earth, was protected by a military that was voluntary and its members considered their lifetime of service to be a desirable profession. But the role of this military had been limited to fighting small wars, putting down internal rebellions in a colony, not taking part in a “total war,” but the First World War was aptly named and changed everything.

In his 2003 article “War and the Public Sphere. European Examples from the Seven Year’s War to World War I,” Richard Stauber wrote that by the Great War, the press and war correspondents were censored and were considered to be agents of the government, rather than representatives of freedom of speech and information. Because the urgency of selling the war to the public was greater on the German side, Berlin allowed war correspondents to go to the Front/s and then, apparently, lie to their readers back home. France and England eventually followed suit but these nations also controlled content as mass media became part of a vast propaganda campaign designed to justify the war and to keep the spirits of the public high and positive. As Stauber wrote of the German, French, and British press, “They had to prove themselves committed ‘patriots’ before they could be accredited as journalists. They had to allow themselves to be ’embedded’ in the pool system organized by the military. They had to submit to censorship. And they had to accept that in general they would stay on the fringes of the action.” Given those conditions, it was no wonder that one of the main sources of “information” was propaganda posters.

According to Pearl James in the introduction to her book, Picture This: World War I Posters and Visual Culture, posters were everywhere, a vital part of the communication between the press and media and the public. The war, she stated, “..unfolded in an essentially nineteenth-century cultural landscape.” This insight helps explain the shock of citizens in Belgium, France, England and finally American at German tactics in the new modern “total war. Posters were part of the modernization of the Great War, she wrote, “..they reached mass numbers of people in every combatant nation, seeing to unite diverse populations as simultaneous viewers of the same images and to bring them closer, in as imaginary yet powerful way, to the war. Posters nationalized, mobilized, and modernized civilian populations..It was in part by looking at posters that citizens learned to see themselves as members of the home front.”

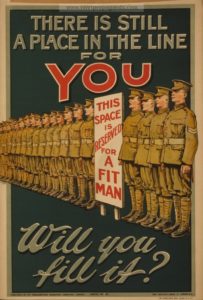

As early as 1908, the government realized that, faced with constant German bellicosity, the military had to be built up. The male population of Great Britain had always relied upon the Regular Army, but they were suddenly needed to participate in a war that would mobilized millions of men. Alone of all the participating nations in 1914, England relied upon volunteers. Without a compulsory “draft,” the nation had to persuade the eligible young men to serve. After serving for a period of less than ten years, a volunteer for the Regular Army became part of the Army Reserve, where he could be called up when needed, for five years. By 1914, there were some 350,000 men standing by, and, as a result of the changes of 1908, they were joined by the newly established Special Reserve. The Special Reserve was “special” because unlike the Territorials, the local part time forces, they could be sent abroad when needed. But both the Territorials and the Special Reserve could be called upon during time of war. It seemed that England was well prepared for any eventuality but no one could imagine a war that could consume an entire army in a month.

The brutality of the fighting in France and the undeniable carnage on the Western Front meant that whatever enthusiasm might have existed in the late summer had vanished by the winter of 1914. While the conventional wisdom asserted the customary “the troops will be home for Christmas,” Field-Marshal Lord Kitchener, a veteran of wars in Africa, correctly predicted that this would be a long and costly war. When Kitchner became the Secretary of State for War, he urged the male population of Great Britain to volunteer to serve their country. As Peter Simkins noted the high point of volunteerism was September. By the new year, it was evident that mere appeals to patriotism would not be enough. According to Simkins in his article, “Voluntary recruiting in Britain, 1914-1915,” “Though 2,466,719 men joined the British army voluntarily between August 1914 and December 1915, even this enormous total was insufficient to maintain the BEF at a strength which would enable it to fight a modern industrialised war involving mass conscript armies. Declining recruiting totals led to increasing calls for compulsory military service throughout 1915. On 27 January 1916, the first Military Service Act introduced conscription for single men of military age, this being extended to married men by a second Military Service Act on 25 May 1916.” These recruits were required to remain in service until the war was over. Depending upon their individual luck, the recruits would spend years in the trenches.

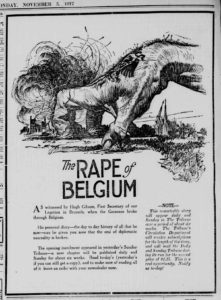

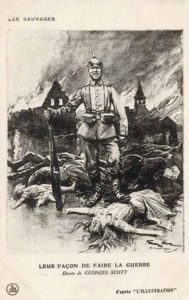

The first wave of recruits were stirred by the inspiring sight of posters, featuring the imposing Lord Kirchner pointing his finger in their direction, reading “Britons” above the stern faced Lord, beneath which were the words “Wants You.” “Join Your Country’s Army. God Save the King” was printed below. The image was simple and compelling and personal with the military hero directly addressing hopefully patriotic young men. The direct gaze and the pointing finger of a national symbol would be copied in America by James Montgomery Flagg who would change little in his poster of 1917, needing to state only “Uncle Sam Wants You.” Enough said. In England, men joined the army by the hundreds of thousands. But one hundred thousand was not enough. Two hundred thousand was not enough. The maw of war was open wide. By 1915, a vast propaganda machine was beginning to roll and it used, as its first fodder to convince young men of the dangers presented by the Germans, the “atrocities” committed in Belgium and northern France against civilian populations. Previous essays have discuss the way in which the Germany army attacked and massacred peaceful civilian populations in Belgium and have discussed the willful destruction of cultural property and architectural treasures. Rape and looting and atrocities were widely reported by the mass media, by now fully developed and devoured by a largely literate population. Posters of the suffering of Belgium, the nation that angered the Germans by resisting being invaded, focused on the bravery of the nation and of the suffering of the inhabitants at the hands of the “barbarians” and “savages.”

In May 1915, the British government produce the Bryce Report, or The Report of the Committee on Alleged German Atrocities, which was undoubtedly part of a pattern of the government participating in the production of propaganda in its sensationalist description of lurid details. Despite the emotional content, the amounts were accurate and correct and well suited to the public mood during the war, but, after the war, the vividness of the descriptions seemed distasteful and not objective enough in a world that wanted to forget and move forward. Nevertheless, much of the material came from captured diaries belonging to German soldiers. As the Bryce Report stated of these primary documents, “They have been translated with great care. We have inspected them and are absolutely satisfied of their authenticity. They have thrown important light upon the methods followed in the conduct of the war. In one respect indeed, they are the most weighty part of the evidence, because they proceed from a hostile source and are not open to any such criticism on the ground of bias as might be applied to Belgian testimony.” The team of investigators and lawyers who listened to the depositions of eye witnesses went from town to town, chronicling the atrocities at each location. An entire segment of the Report detailed the terrible treatment of women and children, the innocents of war:

The officers ordered the houses to be set on fire, and straw was obtained, and it was done. The man and his wife and the child were thrown on the top of the straw. There were about 40 other peasant prisoners there also, and the officer said: “I am doing this as a lesson and example to you. When a German tells you to do something next time you must move more quickly.” The regiment of Germans as a regiment of Hussars, with cross-bones and a death’s head on the cap. Can anyone think that such acts as these, committed by women in the circumstances created by the invasion of Belgium, were deserving of the extreme form of vengeance attested by these and other depositions?

As has been established in earlier posts, the Germans were waging war for the honor of German Kultur, attacking inferior French Zivilization, and, in doing so, the out of control military played directly into the hands of British propagandists. With atrocity propaganda, convincing the British population of the dangers posed by the “Hun,” Belgium was gendered as female. A helpless woman, Belgium was “raped,” and Germany became a brutal male animalistic rapist, both symbolically and literally. Thus in the space of a few terrible months, Belgium had gone from being the brave David holding off against the German Goliath and had became the helpless maiden ravished by an impeccable and vengeful hyper-masculinized foe. The propaganda posters, however, elided the fact that, once the nation was thoroughly conquered and subdued, it was further raped, plundered for supplies for Germany’s war efforts. Thanks to a stubborn British blockade of German ports, considered an “atrocity” by Germany, the Belgiums starved, so that the Germans could eat. The Belgiums would be fed by an American organization, the Commission for Relief in Belgium, headed by Herbert Hoover, because the British refused to help the Germans by feeding the hungry women and children that appeared in their posters.

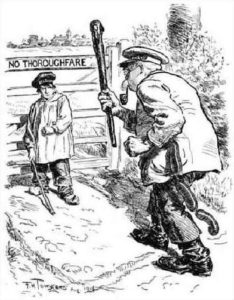

Germany replied to the Bryce Report with their own account of the conduct of the Belgiums against the occupying Germans. The White Book, an infamous document not to be confused with the earlier White Book, a justification for starting the War. The new White Book was issued in May 1915, in keeping with the habit of issuing “books” or documents under the title of a color. The White Book was described by Sophie de Schaepdrjver as a compendium of lies and justifications: “At the same time, May 1915, the German government produced its own report (the so-called German White Book) which claimed that the Belgians had conducted a premeditated ‘People’s War’, with sadistic excesses, against its army. This report relied on hearsay and heavy editing, omitted evidence from within the German army that contradicted its claims, and suppressed depositions by civilians for the same reason. In response, the Belgian government-in-exile published a detailed refutation (the so-called Belgian Grey Book) with lists of civilian victims; and the Belgian sociologist Fernand van Langenhove invalidated the ‘People’s War’ thesis in his 1916 study The Growth of a Legend, which proved on the basis of German documents that the franc-tireur story had been a mass delusion, a ‘cycle of myths.'”

The war of words was not just between Germany and England but both salvos from both sides were directed to an American audience, to a neutral nation that must be persuaded to take a side in a conflict a continent away. Accordingly, the White Book reported (totally without fact) on the conduct of the people of Bruges: “Men, women and children opened such a frightful fire on the enemy that the first ranks tumbled one on the other. The Germans nevertheless entered the village streets, cavalry in front, infantry behind, while the exasperated populace did not cease to overwhelm the enemy with its fire. The women poured boiling oil and water on the German soldiers who rolled on the ground howling with the pain.”

It has been established beyond doubt that Belgian civilians plundered, killed and even shockingly mutilated German wounded soldiers in which atrocities even women and children took part. Thus the eyes were gouged out of the German wounded soldiers, their ears, noses and finger-joints were cut off, or they were emasculated or disemboweled. In other cases German soldiers were poisoned or strung up on trees; hot liquid was poured over them, or they were otherwise burned so that they died under terrible tortures.

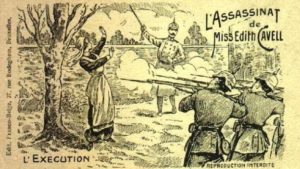

One of the most important poster campaigns galvanizing the British, the French, and the Americans mourned (in rage) the execution of the British nurse Edith Cavell. A respectable middle aged woman, doing her patriotic duty for her country, Cavell died because she helped British soldiers escape from captivity in Belgium. Following on the heels of countless atrocity stories over an entire year, the tragic death of Cavell on October 12, 1915, shocked the sensibilities of those who considered women the revered and sacred gender. Her death stood for all the other women whose honor had been assaulted by the Germans, daily demonstrating their lack of civilized behavior. The use of women in propaganda as helpless victims, no matter how brave they were in real life, was exaggerated in mass media. from posters to films, all depicting Cavell as much younger than her actual forty-nine years.

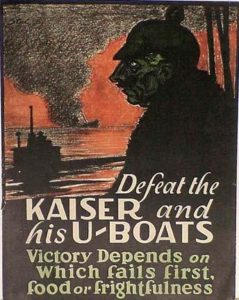

From the propaganda posters and the newspaper accounts published by America, it was clear whom the citizens of the United States eventually believed. There were many German Americans very sympathetic to the home country but the sinking of the Lusitania by a German submarine in 1915 caused a shift in public opinion. America wanted to remain neutral but its sentiments began to shift towards the beleaguered Belgiums and towards the French and British fighting in the trenches. The attack on the Lusitania, full of innocent civilians, including women and children, many from America, on May 7 caused Americans to develop the British attitude towards the “Huns” and the French contempt for the “Boche” as being “uncivilized” in conducting a stealth war, hidden below the waves. The year 1915 was the year in which Germany with its Zeppelin raids over London fully demonstrated its “frightfulness,” a uniquely British phrase, on the battlefields of the land, sea, and air.

Although the luxury liner, flying a British flag, had been warned that any such ship would be liable to attack by Germany, the attitude was as one survivor stated, “I don’t think anyone took very much notice of this because they thought, well, no nation would dare go to the point of sinking a passenger liner and especially a liner so famous as the Lusitania.” To the German submarine commander, Captain Walther Schwieger, the Lusitania was flying the wrong flag and, in keeping with the German position of “unrestricted submarine warfare,” must be sunk. One hundred twenty-four Americans, including ninety four children, died, dealing a blow to German hopes of American neutrality. As the First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill expressed it, “The poor babies who perished in the ocean struck a blow at German power more deadly than could have been achieved by the sacrifice of 100,000 men.” For decades it was not confirmed what the German knew, that the liner was carrying arms, concealed in its cargo hold and therefore the Lusitania was “fair game.” After the entire “civilized” world expressed outrage and horror, Germany prudently halted “unrestricted” submarine warfare and in 1917, without mentioning the Lusitania, Schwieger received the “Pour Le Merite” medal, or “Blue Max” but six weeks later his ship struck a mine six weeks later and the man who sunk the Lusitania was killed.

William Lionel Wyllie. The Track of the Lusitania (1915)

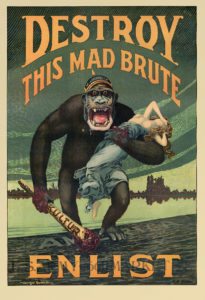

When America finally joined the Great War in 1917, its own propaganda machine began to print posters. Easily the most famous and most notorious was the “Destroy This Mad Brute” enlistment entreaty by Henry Ryle Hopps. Designed well before the 1933 film, King Kong, the poster depicts the by now well-developed idea of Germany. Wielding club with the word “Kultur” on it, the “mad brute” is carrying a supine and swooning woman, breasts exposed, and is wearing a Pickelhaube or spiked helmet. The ape is sporting the mustache of the Kaiser with the jaunty upturned ends but this civilized style is clearly and pointedly not in keeping with the beastliness of the Germans. Americans had always associated the “savage” with Africa and the inherent racism in the nation and its long struggle with slavery, still a living memory in many of its citizens, makes this poster a racist proposition. Its imagery is drawn directly from Southern attitudes towards black males who were apt to rape white women, a representation that was easily transferred to another uncivilized being, a German ape. It is doubtful that the Americans or the artist understood the complex meaning of “Kultur,” but the main point of the poster was that the Germans were “brutes” who raped women in Belgium and sunk ships carrying babies and fought unfairly with poisoned gas. Their uncivilized behavior had, from the very beginning of the conflict, had stripped the Germans of their most prized possession, “Kultur.”

For the French people, the menacing presence of the Germans at the gate was “frightful.” The French army had fought off the German invasion into France, a thrust inward that came so close to Paris that the Eiffel Tower itself seemed to cower. But then the German army had to pause and regroup, giving the French a chance to push back so that they “won” the Battle of the Marne. But in this first month of the War, the French lost so much of its army that the nation would literally not recover from that blow. Literally on its knees, every day, the army fought in the trenches to keep the “Boche” at bay. For their part, the British realized that the Battle of the Marne had been a close call for the French and thus for the British Empire and brought in the Navy to blockade the German ports as part of what was becoming a war of attrition. The first year of the war had shown the full extent of the German “beastliness,” and the people of the British Isles were well and truly alarmed. The posters depicting Germans as ape-like creatures on the loose echoed the fears of both the French and the British, feelings of terror exacerbated by reports of widespread rapes, looting, massacres, and destruction of property in Belgium. The next post will continue the discussion of the psychology of posters during the Great War in relation to the role of women at War.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.