GERMAN ARTISTS AT WAR

Part One

The Art of Lying

In 1928 Edward Bernays, the American nephew of Sigmund Freud, wrote on a newly significant topic–Propaganda. Bernays was well acquainted with his uncle’s theories of human psychology and injected tools of manipulating minds by putting pressure on emotional tender spots into his chosen field public relations. In the early twentieth century, Freud’s theories were new and the idea that the subconscious mind could be prodded by subliminal signals would have been unfamiliar with most people, even the educated. As a nephew, Bernays, however, had a privileged position and used his insider knowledge of the human mind, and, as a young member of the Committee on Public Information, he helped America during the Great War by convincing the population to support the effort. America came into this worldwide conflict late in the game, during the final year in 1917 and set up the CPI in imitation of London’s Wellington House to disseminate controlled information. While working for America, Bernays had ample opportunity to observe the tactics of other nations and how these countries persuaded their people to fight the war. Ten years later, Bernays wrote Propaganda, one of the first books on the subject. Even at that time, Bernays, who had transitioned into advertising, regarded propaganda as a positive. It is surprising to read his opening sentences:

The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country. We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of. This is a logical result of the way in which our democratic society is organized. Vast numbers of human beings must cooperate in this manner if they are to live together as a smoothly functioning society.

Bernays acknowledged that propaganda had acquired a bad reputation, but he also understood that, because of the newly omnipresent mass media, the fine art of persuasion had penetrated and permeated the social fabric:

The minority has discovered a powerful help in influencing majorities. It has been found possible so to mold the mind of the masses that they will throw their newly gained strength in the desired direction. In the present structure of society, this practice is inevitable. Whatever of social importance is done to-day, whether in politics, finance, manufacture, agriculture, charity, education, or other fields, must be done with the help of propaganda. Propaganda is the executive arm of the invisible government.

In the same year, 1920, a Labor member of the British Parliament, Arthur Ponsonby wrote, Falsehood in War-Time, Containing an Assortment of Lies Circulated throughout the Nations during the Great War: Containing an Assortment of Lies Circulated throughout the Nations during the Great War. The strangely long title indicated that, in his opinion, all nations told lies to their people, especially in war-time. He wrote,

Falsehood is a recognized and extremely useful weapon in warfare, and every country uses it quite deliberately to deceive its own people, to attract neutrals, and to mislead the enemy. The ignorant and innocent masses in each country are unaware at the time that they are being misled, and when it is all over only here and there are the falsehoods discovered and exposed. As it is all past history and the desired effect has been produced by the stories and statements, no one troubles to investigate the facts and establish the truth.

He added,

The psychological factor in war is just as important as the military factor. The morale of civilians, as well as of soldiers, must be kept up to the mark. The War Offices, Admiralties, and Air Ministries look after the military side. Departments have to be created to see to the psychological side. People must never be allowed to become despondent; so victories must be exaggerated and defeats, if not concealed, at any rate minimized, and the stimulus of indignation, horror, and hatred must be assiduously and continuously pumped into the public mind by means of “propaganda.”

As previous posts have pointed out, when the Great War began in August of 1914, England had an interesting problem–with only a small professional army and a scattering of territorials, how to fight a war that required millions of men? The answer had to be two-fold, first, shame men into fighting for their country and second, keep the truth of the conditions of the war itself from the public and from future soldiers. The Manchester Guardian newspaper was opposed to the War, but quickly realized the danger posed by German aggression and the editor C. P. Scott wrote, “Once in it, the whole future of our nation is at stake and we have no choice but do the utmost we can to secure success.” Apparently, Prime Minister Lloyd George trusted Scott for in 1916, he confided about printing true accounts of the War, “If people really knew, the war would be stopped tomorrow. But, of course, they don’t know, and can’t know.” England refused to allow journalists report from the battlefields unless they were closely watched and under total government control. Once blanket censorship descended upon the War, the distance from the actual fighting allowed the government and its multiple agencies to suppress dissent and oppress true accounts of trench warfare. While individual soldiers must have confided somewhat with their friends and families, mass media was effectively muzzled. For the good of the nation at war, the state of the psychology of those who must fight had to be maintained. High spirits and high hopes on the home front were as valuable as munitions.

The Great War was unique in its own time–it was the first modern total war, requiring the mobilization of men of military age and the support and participation of the entire public. It was France that began to practice of total mobilization of the army and the public during the French Revolution. The crisis was a very real one–revolutionary France was surrounded by enemies that were hostile and determined to crush the rebellion against the divine rule of monarchs. The entire nation rose to its own defense and the Revolutionary government instituted a novel idea, the levée en masse, referring to a draft or mass conscription and to the rising of the population to fight as a totality. The levée en masse was continued under Napoléon and after the fall of his nephew’s Second Empire, the Third Republic used the idea of total participation as a tool of national honor. After the stinging defeat of the Franco-Prussian War, France kept its national identity intact with the hope of revanche warming the heart of the body politic. Germany, however, emerged from their stunning victory strangely unsatisfied and the two nations crouched into defensive postures that predicted and eventually precipitated a new war. The distinction between Germany and the other European nations was that Germany wanted to go to war, meaning that Germany had to prepare the people for war and that the nation had to give those people a good reason to go to war. Enter propaganda.

All countries go to war with a set of beliefs and an array of assumptions. Germany believed it was directly threatened by enemy nations, mostly France and Russia, now arrayed together into an Entente Cordiale. Germany also believed as a consequence that it was entitled to a preemptive attack and would find any excuse to strike at France. Germany assumed that it could surge towards France through Belgium, which would obligingly lie down and allow the German army to march unmolested through their helpless borders. The Schlieffen Plan had been in place since 1905 and its mastermind, General Count Alfred von Schlieffen himself based the plan upon two major misconceptions: that Russia, France’s ally, Russia, would be slow to mobilize and that Belgium would prove to be no obstacle to its military might. He was convinced that France was Germany’s greatest enemy and that when Germany marched through hapless Belgium and defeated France in about six weeks, England would be cowed into staying out of the fray. The Schlieffen Plan became not just a German strategy but also a mindset upon which all their policies would be built and all the wartime plans would be based. The problem for the Germans was that, under this plan, Germany would appear to be the aggressor and the one condemned for starting a war. In order to seize the first available opportunity to start a war, Germany had to prepare the nation to believe that France was at fault, justifying their role in the conflict. The assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajavo on July 28, 1914, provided the long-awaited pretext. Germany goaded the Austro-Hungarian Empire into attacking Serbia, the site of the tragedy. Russia, treaty bound to defend Serbia, sprang into action, and France, treaty bound to aid Russia also declared war. The stage was set and the drama could unscroll, according to the preexisting script.

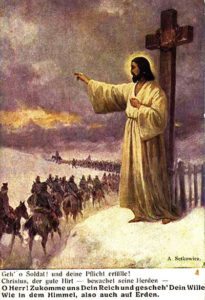

Everyone involved assumed that the war would be over by Christmas. And of course, regardless of whatever Plans that had been laid, God was on the side of the Germans, a strongly held belief system that could be held only as long as the people believed that right and morality were owned by the Germans.

As Jeffrey Verhey pointed out in his 2000 book The Spirit of 1914: Militarism, Myth, and Mobilization in Germany, the August 1 entry into the war apparently resulted in an overwhelming surge of nationalism on the part of the German people, whose minds were seized with patriotism, the “spirit of 1914,” which had to be harnessed and maintained. Whether or not the entire nation lost itself to this fervor is perhaps beside the point because as Verhey noted it was the myth itself that counted as the six-week war stretched into years. “In German propaganda, the myth of the “spirit of 1914” was a means of mobilizing enthusiasm. The successes of the German army against a numerically superior opponent were interpreted as the product of a greater faith against an over a rational opponent, a victor of “faith over disbelief..As morale declined and “enthusiasm” faded, propagandists repeatedly invoked the “spirit of 1914..”

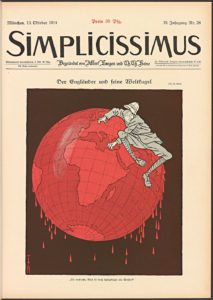

The Germans feared and envied the British Empire and yet the Kaiser did not expect the English to come to the aid of the French, much less immediately set up a blockade hemming Germany into its own coastline. To the Germans, Great Britain was a bloodthirsty and greedy presence, dominating the globe and was a menace to Germany’s desire to expand its own comparatively small empire. Some of this empire was European, including Silesia, East Prussia, West Prussia, South Prussia, Alsace-Lorriane and a slice of Belgium. The rest of the empire in Africa–Togo, Nambia, Tanzania and territory north of the Congo River–were acquired of the Scramble for Africa. In 1884 through 1885, thirteen nations in Europe and the United States were summoned to a conference in Berlin by Otto von Bismarck. The conference carved up Africa among them and established “rules” for the colonization of an entire continent, deemed to be “Dark.”

Despite a growing economy and a large navy, but the beginning of the War decade, Germany was uneasy and presented to the German people an image of a new and valorous nation beset by ancient enemies whose values were alien to Germanic peoples. Thus, in propagandistic discourse the myth of “Germany” not only described the community that the soldiers were dying for, it also discussed eternal, transcendent, religious questions, offering hope to the believers. In other words, it valorized a mythological as opposed to a critical epistemology. Faith was opposed to rationality, belief to critical thought.” The German artist, Freidrich August von Kaulbach painted this “community,” a nation of people molded together with one spirit as “Germans.” Germania, clad as a valkyrie, one of Odin’s warriors, tapped into the belief that the German tribes were different, holding themselves apart from their Romanized neighboring tribes. This nationalistic purity was the deep bond that held the German people together during the worst of times.

The propaganda posters produced by mostly nameless German illustrators reflected this mystical, magical and religious belief system. An important gear of the propaganda machine was the righteousness of the German cause. Germany was innocent, Germany was provoked, Germany had no recourse but to invade Belgium, which, in fact, did resist, Germany was on the side of all things good and right. In the poster below, the Kaiser himself insists he did not want the war.

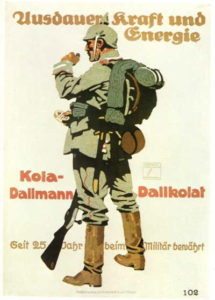

The military is always noble and brave and the artists showed the soldiers as clean and strong and idealized, all mud and blood wiped away lest the sights of fighting offended the German people. One of the major purposes of propaganda was to subdue underlying political and social problems with a call to arms that would knit the German people, regardless of class into a “national community” or Volksgemeinschaft. However, as David Welch wrote, that despite the fact that Germany had an early and “sophisticated notion of propaganda,” “..the eventual collapse of Germany was due less to the failure to disseminate propaganda than to the inability of the military authorities and the Kaiser to reinforce this propaganda, and to acknowledge the importance of public opinion in forging an effective link between leadership and the people in conditions of ‘total war.’ Those in power were unable and unwilling to reform German society along the lines demanded by public opinion.“

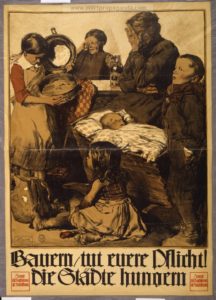

This book, Germany and Propaganda in World War I: Pacifism, Mobilization and Total War, published in 2000, argued that, although the authorities failed to pay heed to public needs, the mere presence of propaganda during the War, acknowledge the need for public support of the War and, at the end of the War, public opinion emerged as an important element in politics. If the Great War was the total war that ended the “cabinet wars” of the previous century, in which war was confined to designated battlefields to be fought by professional soldiers at some distance from civilians, then the public and its reaction to a prolonged struggle became a powerful player to be ignored at the leaders’ peril. The British blockade of German ports meant almost immediate shortages that brought misery and hunger to the German people during the War. While the propaganda poster correctly blamed the British for the starving children but left the question of how patriotism could feed the people unanswered. David A. Janicki described it the blockade was a “Weapon of Deprivation.” “Without it,” he wrote, “the war could have potentially gone on even longer, but because of it, the world’s preeminent land force was left with no other choice than to surrender as the seeds of revolution brewed among its population.”

As Welch wrote, “The duration of the conflict, the Allied blockade, food shortages and the failure to introduce social and political reforms eventually wore down the German people. It is a measure of the effectiveness of the propaganda machinery–which appealed to traditional German values of obedience, duty, and patriotism–that a consensus (of sorts) was maintained for so long.”

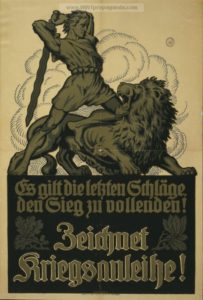

To raise the money to fight the War, the Germans had almost ten separate campaigns, more than France or England, but all the money could not help a nation mired down in an apparently endless war. When the Russians pulled out of the War, freeing the German soldiers on the Eastern Front to fight on the Western Front. The German military was deliberately waging a war of attrition, with the intention of bleeding France and England white and now they had the edge in men. Their last push, the “Kaiser’s Battle,” was their last chance. If the Germans lost, there were no reserves to fall back on, while the ranks of the Allies were being swelled by a young, healthy and apparently endless American army, new to the war. The spring offensive of 1918 came within fifty-six miles of Paris but there the Germans were held in place. And then almost exactly four years after the War began, the end came for the German on August 8 when the Allies broke through the German lines in Amiens. The German troops, faced with enemy tanks, their own lack of supplies, the first signs of an influenza epidemic in their ranks, surrendered in the thousands. Without hope, the morale of the German soldiers broke down on “Black Friday.” Despite warnings shouted in posters, such as the one below: ‘This is how it would look in German lands if the French reached the Rhine,” the army and the navy would not and could not fight any longer.

Six weeks later, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and General Erich Ludendorff broke the news to the Kaiser that the army could go on no longer. In the confusion that followed until the November Armistice, the German people reacted in shock. Their nation had not been invaded; they had never seen an enemy soldier. The German military, the only intact entity not completely discredited was quick to blame the politicians and later the Jews for the “stab in the back,” never admitting their own responsibility for the disaster. The propaganda machine had been all too successful in creating a myth of rightness and goodness and had shielded the German people from the slow deterioration of the military efforts over the four years of the War. After the War, the German people, duped by the propaganda campaigns, were shocked to learn of their “war guilt,” (“sole guilt” or Alleinschuld) that they had started the War and that, in their name, atrocities had been committed. Fortunately, for Germany, atrocity stories had been so exaggerated, that the defeated nation could hide very real war crime behind the wild stories for the rest of the century. For the German people in 1918, the war ended in a long-awaited revolution that drove the Kaiser from his throne and a swirl of social turmoil, laced with shock and disbelief and bewilderment. This public shock not only leaves the impression of an impressive propaganda campaign but also laid the groundwork for the refusal to accept the loss. Contrary to the advice of the American General John Pershing, France and England did not force Germany to admit to the defeat, leaving the door open for conspiracy theories, namely the Dolchstosslegende–the stab in the back–that, according to David Welch, acquired an “almost mystical power. It is therefore not surprising to discover that when the Nazis came to power in 1933, one of the first government departments to be established was the Ministry for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda.”

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.