AFTER THE GREAT WAR

Artists in Germany:

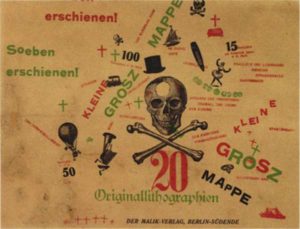

George Grosz and John Heartfield in Dada

Georg Groß was so horrified at the idea of doing his patriotic duty for the Kaiser and country that he went quite mad. The idea of descending into the hellish landscape of what would be called “The Great War” was unsupportable and he proved to be a man who could not be turned into a soldier. Faced with the choice of shooting him or releasing him, the German Army eventually released the artist. In his biography, written in the 1950s, the artist, who renamed himself as “George Grosz” to shake off his German identity, recalled his militaristic Prussian upbringing in Pomerania. His school years were laced with beatings, or what Grosz called ‘the approved principles of education,” and, predictably he was expelled from his school. Along the way, he gathered up a catch-as-catch-can education as an artist in Dresden, Berlin, and Paris. These adventures of a young man were interrupted by the War. “..my fate had made an artist of me, not a soldier. The effect the war had on me was totally negative.” Instead of being flooded with the so-called enthusiasm or steeled by a sense of duty, Grosz was filled with disgust. He wrote, “Belief? Ha! In what? In German heavy industry, the great profiteers? In our illustrious generals? Our beloved Fatherland?” He continued, “What I saw filled me with disgust and contempt for people.” These sentiments of distaste for humanity would guide the attitudes and art of George Grosz for the rest of his life.

Like many young men, Grosz had enlisted, but he quickly turned against the War, which, after a promising beginning quickly devolved into a stalemate. Like many of these young men, he had interrupted his new career as an artist, cobbled together from studies in Dresden at the Art Academy, a school that was part of the Museum of Applied Arts in Berlin, and a stay in Paris. From these solid beginnings in art schools, Grosz honed his abilities as an observer, carrying a sketchbook with him, jotting down all that caught his quick eye. As one might expect of a young man, who had been expelled from school, the military life did not agree with him. The tumultuous years in uniform were paused when Grosz was sent on a leave or a furlough in 1916. It is at this time that he met his lifelong friend and artistic collaborator, Helmut Herzfeld who would change his name that year to “John Heartfield” to protest the war machine. Heartfield and his brother Wieland Herzfelde (who later added the letter “e” on the end) were admirers of the left-wing pacifists, Karl Liebknecht, leader of the Spartacus League, and Rosa Luxemburg, political figures, who were later murdered during the uneasy post-war Weimar Republic. As a follower of these leaders, Heartfield also became a pacifist, and he and Grosz were united in their hatred of German nationalism, which was being pushed forward to justify the war and to bolster the “spirit of ’14.” After Georg became “George” and Groß became “Grosz,” both Heartfield and Grosz found new identities as political artists and as social critics. But being against the war did not prevent Grosz being recalled to the Army, and his reactions to confinement within the military structure became more intense. The Army put him in a military mental asylum, but Grosz was rescued from a firing squad by Count Harry Kessler, an important supporter of avant-garde art. The artist was finally discharged in 1917, declared to be “permanently unfit.”

Having seen too much of the War and its grotesque horrors, Grosz was filled with rage. This intense anger permeated his early paintings, which look like circles of Hell as imagined by Dante. The paintings glow as if populated with fiery coals glowing in a swirling darkness of fear. Structures collapse into a reddened center, a glowing vortex that sucks everything into its baleful center. Explosion was typical of the paintings Grosz made during the War depicting cities in chaos, desperate people, running for their lives, as though he fantasized the consequences of the conflict that Germany began being visited upon the people who supported the Kaiser and his aggressive invasion of Belgium and France. Ironically, Germany would never be invaded during the Great War; its capital would remain untouched, and yet the war was lost. The self-imposed task of Grosz was to shake off the remnants of Expressionism and take up a more precise style, devoid of emotion, better suited to the shock of defeat and humiliation and the consequences of ill-starred War.

George Grosz. Explosion (1917)

After the War ended, Grosz who was primarily a drawer, more comfortable with pen and ink than with brush and paint, joined a like-minded group of artists as angry as he, inspired by the Dada phenomenon in Zurich. Berlin Dada, like all of the Dada movements, was short-lived but provided an important post-war outlet that allowed German artists to react to the difficulties of adjusting to being defeated after a long and grinding war. The city had been abandoned by the government, which fled the turmoil of competing factions, from unemployed soldiers, dangerous Freikorps, and Communists seeking their chance to seize control of the vacuum left by the abdication of the Kaiser. The government moved out of range of the street violence and settled into the small town of Weimar, hoping to stabilize a nation stunned and starving. As was pointed out in earlier posts, the Kaiser’s regime had systematically lied to the people, who were convinced, despite the fact that they were beings starved by the blockade of their coast by the Royal Navy, they were winning. Once the truth of the failure of the last-ditch Ludendorff Offensive, thought to be a success, came to light, and the army collapsed and the navy mutinied, the German people were shocked. By the time Berlin Dada came together, the German people were living under the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, a punitive document which would cripple the recovery of the nation. The Weimar government could not cope with the needs of the desperate citizens, and it seemed that the only people who had come out of the war unscathed were the war profiteers.

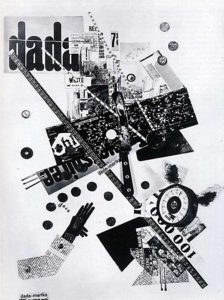

As Dada artist, Richard Huelsenbeck, pointed out, “There is a difference between sitting quietly in Switzerland and bedding down on a volcano, as we did in Berlin.” John Heartfield and George Grosz had created a unique and potent weapon to critique the failures of Germany–the photomontage–a combination of collaged images and typography, appropriated lettering. Later Grosz said that the pair had “..invented photomontage in my South End studio at five o’clock on a May morning in 1916, neither of us had any inkling of its great possibilities, nor of the thorny yet successful road it was to take. As so often happens in life, we had stumbled across a vein of gold without knowing it.”

Grosz and Heartfield. Page Four from Neue Jugen (New Youth) (June 1917)

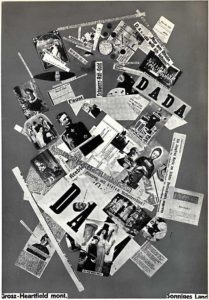

There has been a dispute over who “invented” photomontage, Raoul Hausmann and Hannah Höch or Heartfield and Grosz, but the practice of altering photographs had been practiced by the German propaganda machine to falsify information and to mislead the public. The Dada artists were merely taking up a practice of lies and using it to tell unpleasant truths. The mood was anti-personal and anti-expressionist. Cutting and pasting from anonymous sources and turning the media against itself suited the purposes of the Dada artists in Berlin. Heartfield, for example, considered himself to be an engineer and called himself “monteur.” In his 2012 book, John Heartfield and the Agitated Image: Photography, Persuasion, and the Rise of Avant-Garde Photomontage, Andrés Mario Zervigón referred to what he termed the “agitated image” produced by Heartfield in which the photomontages, composed of borrowed photographs, which were assumed to be tellers of the truth, but, under the Kaiser’s government, were forced to tell lies. The collaborations of Heartfield and Grosz produced photomontages as vehicles for a trenchant criticism of a social system in a meltdown. The two years between their collaborative work at their journal and the Dada collage ironically titled “Sunny Land,” shows a significant growth and development of their play with images and text. The early sprawl has coalesced into coherence, which is expressed with a chaotic assemblage.

Grosz and Heartfield. Sonniges Land (1919)

There is an intensity of frantic motion in the joint work of the collaborating artists that was absent from the more structured and legible work of Haussmann and the sense of “agitation” is approached only occasionally by Höch. Life and Times in Universal City at 12.05 Noon, 1919 on the left and Dada-merika on the right are dense and thick with layered dis-ease, symptomatic of a struggling Republic. As Heartfield warned, as a Dada artist, he was prepared to go to war with “..scissors and cut out all that we require from paintings and photographic representations.”

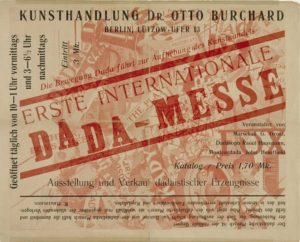

Even though Grosz and Heartfield both worked with photomontage in the early years of the Weimar Republic, their paths would diverge. Heartfield would remain with his collage critiques, becoming the consummate gadfly on the government, and Grosz would torment the authorities with cruel caricatures of a German people at their worst. Violence is always lurking beneath the surface of the works by the Dada artists in the 1920s, and as the installation of the First Dada Messe in Berlin in 1920 suggested, the rage had become an internalized attitude deliberately created by the military which taught its soldiers to kill and maim. No matter how much Grosz and his Dada colleagues mocked the Prussian mentality, the artists who returned from the battlefield had absorbed the lessons provided in the trenches. It is possible that today these suffering souls would be diagnosed as with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, whether or not they had seen active service. The entire nation was reeling from a severe blow and was uncertain of its future, and even the past had suddenly become unknowable. The grounds for truth had been dissolved and with it a possible historical discourse that would allow the country to come to terms with its fate. In light of the condition of Germany in 1920, the use of the word “Fair” to describe the assaulting exhibition in a Berlin gallery owned by Dr. Otto Burchard (an unlikely host, given that he was an expert in Song Chinese ceramics) was entirely mocking. A less joyous environment could hardly be imagined. Despite the obvious rebellious aspects to the exhibition, the show had a very respectable catalog with a cover by John Heartfield and the text written by Heartfield and his brother, Hertzfelde. The introduction named George Grosz as the “Marshal,” Haussmann the “Dadasopher” and Heartfelt the “Monteurdada.”

The invitation to the Messe was hardly welcoming, stating that “The Dadaistic person is the radical opponent of exploitation; the logic of exploitation creates nothing but fools, and the Dadaistic person hates stupidity and loves nonsense! Thus, the Dadaistic person shows himself to be truly real, as opposed to the stinking hypocrisy of the patriarch and to the capitalist perishing in his armchair.”

All of the major artists of Berlin Dada were present at the opening of the provocative Messe. The earlier presentation of Dada works in Cologne, Dada Vorfrühling, which had forced the attendees to step over a urinal placed at the entrance, set the nihilistic tone. The exhibition was a deliberate parody of a decorous academic art salon with the crowded and disorderly dis-arrayed works of art covering walls peppered with phrases about Dada–“Nieder die Kunst,” “Dilettanten, erhebt euch gegen die Kunst.” However, as Weiland Herzfelde explained in his “Introduction to the First International Art Fair,” the show of “Dada products” was also an attack on the art market, with the intent of jolting the public’s idea of “taste” as the reliable guide to purchase, even though all of the “products” (Erzeugnisse)were for sale.

Hausmann and Höch, who is sitting down, chatting with Dr. Burchard, while Baader, Herzfelde, Margarete Herzfelde, Schmallhausen face the opposite direction on the right and George Grosz sits with his with hat and cane near Heartfield

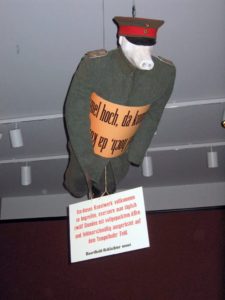

One of the most unexpected “products” was a “sculpture” titled Prussian Archangel, with a placard reading, “I come from Heaven, from Heaven on high.” The “on high” referred not to heaven but to the ceiling and, to the audience, the words would have been familiar, coming from a well-known German Christmas carol. The sign dangling from the Angel’s uniform was a solider’s complaint: “In order to understand this work of art completely, one should drill daily for twelve hours with a heavily packed knapsack in full marching order in the Tempelhof Field,” and the pig’s snout on the face of the officer was an act of contempt by former soldiers. The “sculptors,” John Heartfield and Rudolf Schlichter had succeeded in indicting the Prussian mindset as being responsible for the deliberate slaughter on the battlefields. A recreation of the floating sculpture can only approximate the effect upon the public which had been taught to revere the military. The reverence allowed the leaders themselves to elide the blame for the loss of the Great War and point a finger at those who had stabbed the army in the back–the Jews.

The Weimar authorities, as might be expected, were not amused by the artistic antics, and the artists were charged with defaming one of the few intact institutions left after the War, the German military. The artists were eventually acquitted but they were hardly the only ones to criticize the military and its post-war conduct. After the War, the soldiers, who had fought for their Kaiser and their nation, were abandoned by the people. Disabled veterans, human soldiers who had been changed to cyborgs, could be seen everywhere on the streets, begging. Otto Dix, a decorated soldier, was on hand with a painting that subsequently disappeared, War Cripples (45% Fit for Service) one of four paintings the artist executed featuring newly mechanized bodies in 1920. George Grosz and John Heartfield also contributed their recreation of the new unnatural beings with an assemblage of manufactured parts. The name of this sculpture, reconstructed in 1988 as part of a larger reconstruction of the original Messe is long and arduous: Der wildgewordene Spiesser Heartfield. Elektro-mecanische Tatlin-Plastik (Le Petit Bourgeois Heartfield devenu fou. Sculpture Tatline électro-mécanique). Like the painting by Dix, this object was completed in 1920 and in English means, The Middle-Class Philistine Heartfield Gone Wild (Mechanical Tatlin Sculpture.) In keeping with the primitive means with which wounded men were reconstructed, the humanoid was re-made of a tailor’s dummy, a revolver, a doorbell, a knife, a fork, the letter “C” and the number “27” sign, plaster dentures, an embroidered insignia of the Black Eagle Order on a horse blanket, an Osram light bulb, the Iron Cross, stand or a base for the mannequin, and what is described as “other objects.”

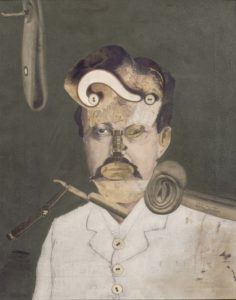

Working alone, Grosz produced a photomontage with a similar theme, a man turned into a mechanical apparatus in the frantic efforts to put the scattered pieces of shattered people together again.

George Grosz. Remember Uncle August, the Unhappy Inventor. Ein Opfer der Gesellschaft (1919)

The “Unhappy Inventor” referred to the defaced oil portrait of Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the Weimar Republic. The reconstruction/deconstruction of the President referred to the impossibility of holding competing factions together. As the head of the Social Democrats under the Kaiser, Ebert attempted to support the government but his party did not have enough power to force Germany to negotiate a peace and avoid a terrible defeat. During the War, the competing parties, including Ebert’s own and the Catholic Center Party and the Democratic (or Progressive) Party joined to form the Black-Red-Gold coalition in reference to the colors of the flag flown during the failed liberal revolutionary uprising of 1848. After the War Ebert established a coalition government of which he was the president, but the foundations of this fragile unity were unstable. The Communists had peeled off years earlier, and Prussia refused to join the new Germany, while the Freikorps organized to defeat the Communists. The Weimar Republic, then, was put together as precariously as a photomontage, without a strong center to hold the factions together. The Black-Red-Gold union was defeated in 1920, a year after Grosz completed the “portrait” that predicted the internal disunion of a collaged and dismembered government. The government, the society and the culture of Germany that gave violent birth to Berlin Dada was chopped up, amputated, and pieced together with tenuous joints.

Otto Dix. War Cripples (45% Fit for Service) (1920)

In examining the complete context of the early years of the Weimar Republic, during which the pieced together soldier now the detritus of a lost War, was all too present, it becomes obvious that there is a connection between the emergence of photomontages and the cyborg that had come to inhabit Berlin. As Matthew Brio pointed out in The Dada Cyborg. Visions of the New Human in Weimar Berlin, the word “cyborg” did not exist in 1920 but the concept of “..the cyborg as a figure of modern hybrid identity, was central to the practices of the Berlin Dada artists.” He continued, “Thus, when the Berlin Dadaists presented the cyborg as representing a new form of hybrid modern “identity,” they were influenced by a wide variety of conceptual systems already in place in their culture that modeled subjectivity as cyborgian, that is, as systematic, constructed, and mutable. Although the theoretical systems that various cultural practitioners cited in their works were different (as were their degrees of access to the same cultural systems), they were all fundamentally engaged with reimagining what it meant to be human in the modern world.” In this new world, a Germany without a modern identity, men without their original bodies, lacking a wholeness and offered only an incomplete hybridity, the bits and pieces of photos, and the montages of words and blizzards of letters were the legible entities of the Weimar Republic.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.