PORTRAITURE REBORN

The Likeness as Blank Parody

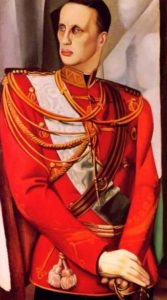

Portraiture had its greatest days in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries–think of Thomas Gainsborough’s proud aristocrats and of Thomas Romney’s posed nobility–consider the magnificent likenesses by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, whose female sitters wore the most stylish gowns of their time–recall the causal bravura brushwork of John Singer Sargent uplifting the nouveau riche into mortality. One might even consider the merits of a photographic likeness, which, when well done, could be iconic for the subject. But what all these examples have in common is the goal of establishing a place in society. Portraiture was always a joint project, between the artist and the client, in which the pair collaborated on a project of self-fashioning. There was no reason why modern portraiture could not have continued in this vein during the early decades of the twentieth century. In Paris, Tamara de Lempicka, one of the great portrait artists of the century, gave new identities to the displaced aristocrats set adrift by the Great War, living precariously in France. But, in Germany, the question of, indeed, the very need for portraits was in question. After a war which was lost, the nation became a Republic and the long-suppressed demand for socialism emerged and the client base for traditional portraiture, the ruling class, was damaged by defeat and shame. And yet, it was during the Weimar Republic that modern portraiture emerged, shorn of its traditional raison d’être.

Tamara de Lempicka. Portrait Of S.A.I. Grand Duke Gavriil Kostantinovic (1927)

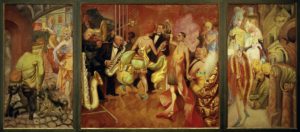

In one of those odd coincidences that remind one of the futility of war, at the Battle of the Somme, there was a gathering of luminous minds and talents, albeit on the opposite sides of no-man’s land. English writers, Siegfried Sassoon, C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkein faced the German artist, Otto Dix (1891–1969). Another day and another time, these soldiers would have been friends. Dix spent almost ten years after the Great War purging his system of his memories, of his suffering as a soldier while expressing his sympathies towards his fellow veterans. He evolved from the brave patriot who had served his nation honorably to an artist of this new and novel post-war period. The last great painting of his recovery period was Gross Stadt (Metropolis) of 1928 in which Dix shows the Weimar Republic in all of its dubious glories. The work is a triptych, mocking an ecclesiastical altarpiece, which used to reveal religious truths to the illiterate. The truth of Gross Stadt is that life has moved on, leaving the war and its casualties aside. On the left and right panels, the war wounded, still not cared for a decade later, still wearing their uniforms, are begging in the streets. But dogs bark and the crowds pass on with distaste and indifference. The central panel is full of the full-blown cultural explosion that enlivened the dark days of the Republic. One could get lost in the pleasures of a jazz band from America and dance to the music, mingling with an exotic cast of characters. Despite the gravity of his paintings, Dix himself loved to go dancing with his wife and the two were so good with the modern dances that they toyed with the idea of becoming professionals. Clearly, the painting as a whole is an indictment of a careless society which has decided who to throw away–honorable soldiers–and who to celebrate–sexual adventurers and hedonists. The “cast of characters” referred to earlier provide a clue to the future direction of Dix: his self-imposed mission of portraying the new people populating the Weimar Republic.

Otto Dix. Metropolis (1927-28)

In his review of Peter Gay’s seminal book Weimar Culture. The Outsider and Insider, Walter Laquer wrote, “There was no place like Berlin in the 1920’s. The capital of the modern movement in literature and the arts, pioneering in the cinema and theater, in social studies and psychoanalysis, it was the city of “The Threepenny Opera” and “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari,” the cradle of the youth movement and the haven of unheard-of sexual freedom. The Mecca of a whole generation of Isherwoods, it has entered history as the center of a new Periclean age.” As Laquer noted in his 1968 article “Berlin, Brecht, Bauhaus and a Whole Generation of Isherwoods,” the achievements of the culture was not appreciated by the “ordinary” Germans. “The advocates and the enthusiastic followers of this avant-garde movement came from a small unrepresentative layer of German society; left-wing or liberal, largely Jewish, it was concentrated in Berlin and a few other big cities. It had no popular success at the time; in the list of contemporary best sellers one looks in vain for the famous names of the twenties..” In a memorable sentence opening his book, Peter Gay described the Republic in terms of “Its tormented brief life with its memorable artifacts, and its tragic death–part murder, part wasting sickness, part suicide–have left their imprint on men’s minds, often vague perhaps, but always splendid.” Speaking of the remarkable achievements of this post-war wounded world, Gay stated, “But it was a precarious glory, a dance on the edge of a volcano.”

In other words, the outstanding individuals of the Republic, the artists and writers, who fabricated the post-war society, were new people, who, in earlier years, would have been marginalized and on the fringes or even suppressed and locked away in a closet. With non-traditional ethnicities and origins, these strong-minded highly individualistic Berliners came from the middle class where a nice photograph would serve as a family portrait. Otto Dix seemed to have decided to update portraiture, pulling the practice away from gentle flattery and aggrandizement and pushing the exercise towards the period proclivity for “New Objectivity.” The meaning of this umbrella phrase which covers unrelated but like-mind artists brought together in a 1925 exhibition in Mannheim. The director of the Kunsthall, Gustav F. Hartlaub, coined the term “Neue Sachlichkeit” to describe what he saw as a tendency towards a new modern realism that stressed objectivity. But Felix Roh found a term he thought better fit the disconcerting loss of the familiar when ordinary objects were subjected to prolonged scrutiny: “magic realism.” The term, then, was a curator’s creation, designed more to provide an alternative to Expressionism and to hopefully to call attention to a new movement than an attempt to describe a new era or a new way of thinking. Since then art historians have struggled with the translation and its meaning, and a long list of possibilities unfolded. In her book, All Consuming: The Tiller-Effect and the Aesthetics of Americanization in Weimar Photography 1923-1933, Lisa Jaye Young provided some of the scholarship on this topic, with descriptions of “function,” “thingness,” “practical,” “straightforward,” “conceptual rationalism” or “impartial.” In 1927, George Waldemar linked the movement to a particular kind of modernism: “The Neue Sachlichkeit is Americanism, the cult of the objective, the hard fact, the predilection for functional work, professional, conscientiousness, and usefulness.” A few years later, Fritz Schamlenbach, a contemporary of Hartlaub, insisted that the curator was referring to a “mental attitude.”

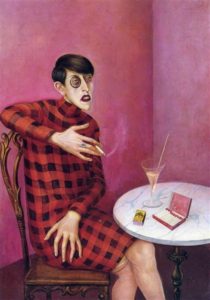

Dix was a native of the old Baroque of Dresden, where he spent most of his artistic life. Many of his portraits were of the citizens who were his friends and colleagues. But the artist also went to Berlin and lived there from 1925 and 1927 in the cultural capital of the Weimar Republic. How could he not? It was Berlin, not Dresden, that defined the period. In the exhibition catalog, Glitter and Doom: German Portraits from the 1920s, Sabine Rewald noted that Dix came to Berlin to paint the Weimar Republic as its people. Upon seeing the journalist Sylvia von Harden “when she left the Fomanisches Café, Berlin’s foremost literary hangout, one night in 1926.” “I must paint you,” he shouted because she “represented their era.” Von Harden, a woman, a lesbian and a journalist, a rather aggressive profession but perfect of the New Woman (with a new name), wrote of the encounter she had with the artist who made her famous in 1959, while she was living in England. Dix was fascinated with what Von Harden described as her “dull eyes, ornately adorned earlobes, long nose, thin mouth, long hands, short legs, and large feet..” In her oddities, Sylvia von Harden represented the Neue Frau simply because, as her monocle implied, she made her way in a world hostile to her through the power of her will and her intelligence. Many Germans disapproved of the New Woman, newly liberated after the War. Already emboldened by wartime work, these women began to push into mainstream society, leaving home and all of its domestic comforts behind and granting herself freedom from marriage by using birth control. Crossing her legs like a man, asserting herself in a red-checked dress, von Harden sports an Eton cropped hair cut (bubikopf) and flaunts her large and handsome hands, one of which is wearing a handsome ruby ring and holds a cigarette. She smokes, she drinks and she hangs out at cafés, wears hard red lipstick, accented by her dress the interior of her cigarette case and the corner walls of the bar. The only relief from the sea of red is the white marble table top and the yellow box of matches. Von Harden’s hose are rolled above the knees, just above her skirt, and would be invisible when she stood up, but Dix reveals her well-groomed and well-dressed knees, with a glimpse of a stocking.

Otto Dix. Sylvia von Harden (1926)

Although this is the most famous portrait that Dix made in his efforts to depict the times in which he lived, von Harden is unique in that she is the only respectable New Woman he painted. More often than not, for Dix, the New Woman inhabits the world’s oldest profession, prostitution. These are the women that fascinate Dix, who, like an early twentieth century Toulouse-Lautrec, must have spent a great deal of time in houses of ill repute. The viewer could be excused for concluding that, for Otto Dix, the New Woman was the prostitute, however, with the exception of his wife, all of the women studied by the artist were, by definition, on the margins and the fringes. In a society that regarded women suspiciously, the line that separated von Harden from prostitutes was a thin one. A professional woman, such as von Harden, were perceived as threats, looked up with resentment, as sources of destabilization. In a country where millions of men died, women filled one-third of the jobs in Germany: she was working, he was dead, she was taking a job that “belonged” to the now absent male. But as Dix recognized, these women were victims of the War as well as the men who would never come home or never recover. Many of these women were prostitutes, walking the streets freely and with great visibility because they had no male protector, no father, no brother, no husband. Fresh out of domesticity, forced on their own devices, without sufficient education to own a livelihood, women were soliciting. Had their lives gone the way they planned, these women would have never become prostitutes. It is with these women that Dix ventured into another phase of portraiture, group portraits, but his series of paintings of women who had fallen on hard times becomes an accumulation that coalesced into a critical mass.

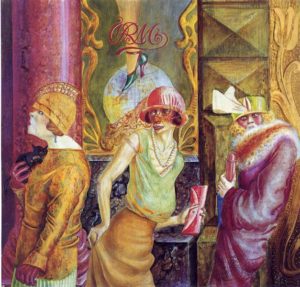

Today Otto Dix’s Three Prostitutes (Drei Dirnen auf der Strasse) (1925) is part of a private collection and rarely on public view. In 2014 the Courtauld Institute of Art posted a short article “The Neue Frau and Fashion in Otto Dix’s Three Prostitutes (1925)”, quoting the distrust with which women were viewed in the Weimar Republic:

Thomas Wehrling, a Weimar cultural critic. His essay ‘Berlin is Becoming a Whore,’ first published in Das Tage-Buch in 1920, explicitly aligns women’s interest in fashion and entertainment with moral debasement: “A generation of females has grown up that has nothing but the merchandising of their physical charms in mind. They sit in the parlors, of which there are a dozen new ones every week; they go to the cinema in the evenings, wear skirts that end above the knees, buy Elegant World and the film magazines…The display windows in the delicatessens are filled for these females; they buy furs and shoes at the most-extravagant prices and stream in herds down the Kurfurstendamm on Sunday mornings.”

Otto Dix. Three Prostitutes (1925)

It has been estimated that, after the War, Berlin had at least twenty thousand female prostitutes, who were a common sight. A contemporary publication put the figure at one hundred thousand, possibly an exaggeration born of the sudden openness with which the women plied their trade. As can be seen in Metropolis, Dix portrayed Berlin as a site of prostitution. Like the wounded and crippled soldiers, the women were the visible signs of the cost of War, and their visible blandishments towards their customers, their blatant immorality all signifiers of a society in shreds. It seemed as if everything was for sale and the “RM” inscribed on the shop window which frames the women, like a splendid portrait, indicated the 1924 introduction of the Reich Mark as the new currency for the Republic. The issuing of a new currency resulted in a re-evaluation of the value of money, and investors and those with savings accounts lost money. The hanging female leg clad in a green high heel shoe is hard to decode but its presence in a shop window almost certainly stressed the theme of commodification, condemning the streets as sites of exchange of flesh. Barbara Hales wrote an interesting article “Blond Satan: Weimar Constructions of the Criminal Femme Fatale” in which she related the way in which the female, both the middle-class shopper (the respectable woman) and the lower class commodity (the prostitute) were both representatives of the Americanized consumer society. “The German press often referred to Berlin as a whore..Berlin as sensual metropolis was a dangerous space where crime and death were associated with the prostitute. It was also a space in which money transactions, political struggles, industrial development, and perceived sexual perversions tore at the fabric of traditional bourgeois German society. The prostitute’s body represented this excess and chaos..” The Glitter and Doom catalog essay on the painting noted that many women dressed in an apparently average fashion in order to avoid being conspicuous but the prostitutes carried and wore recognizable items as codes, conveying specialties and services to their alert customers.

With cheerful vulgarity, Dix seized upon these and other telltale details. The prostitute on the right clutches a large, red phallus like umbrella handle that points to the vulva-shaped ornament on her green hat. Her emaciated colleague in the center trails a long transparent red widow’s veil, an accessory that had become a popular trademark of her profession during World War I, grasps a matching red pocketbook, and cups her hand provocatively on her hip, causing one of the straps of her chemise to slip off her shoulder. The older woman holding a tiny, ugly dog on the left has just passed hem; her disapproving smirk still distorts her sharp features. She is identified as a prostitute by little except her red leather gloves, which perhaps signal some special service.

The portraits by Dix of women have all the signs of a man observing women with fear and loathing, a gaze of the man who is both socially powerful and sexually intimidated. According to all accounts, he was also a man who loved his wife who encouraged his career, despite the controversial topics. If we put Dix in his own cultural context, his portraiture is typical of the period. In Germany, the 1920s was a golden age of portrait painting, as many artists, such as Christian Schad, sought to understand modern life in Europe through studies of those who inhabited the most advanced elements of society. None of the portrait painters of the Weimar period attempted to beautify their subjects. In keeping with the sobriquet “objective,” in all its many meanings, Dix was merciless. In some cases, it is possible to compare contemporary photographs of his subjects with his portraits. Working in tandem the same time as Dix, photographer August Sander also found Sylvia von Harden as an interesting representative of modern Germany. Like Dix, Sander focused on intriguing individuals, mostly of the artistic class, and, like Dix, Sander used the group approach to the lower classes.

August Sander. Sylvia von Harden (1920s)

Dix exaggerated the journalist as a character, a player in the theater that was the Weimar Republic, but, at the same time, as with his prostitutes, he captured the mood and feel of uncertain and disruptive times.Sander makes von Harden seem far less noticeable and far more assimilated into society, calling attention to the many shades and moods of “objectivity” as a mode of expression and examination and as a means of cataloging and classifying the people of Germany. In 1927, Dix was offered a job at the Academy of Fine Arts in Dresden and he returned home, ending his Berlin adventures. Out of an apparently simple genre, portraiture, a number of categories developed in the Weimar Republic. In the next post, the artist George Grosz explored the idea of portraiture as a study of type and as an expression of hate and disgust.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.