The Fate of Fonts

Typography in the 1920s, Part Two

Printing and its old-fashioned fonts had long been viewed as problematic, and, in the nineteenth century, the English designer, William Morris, set out to revive what had once been an art form with the famous Kelmscott Press. His “reform” of mass-produced books was a prelude to the modern movement in typography that actually originated in England before and after the Great War. As Robin Kinross wrote in Modern Typography: An Essay in Critical History,

The movement took up Morris’s fight for high standards and for an awareness of aesthetic qualities in printing: as at least one of its leading members reported, the sight of a Kelmscott book had provided the shock of excitement that started a life-long engagement with typography. But the reformers dissented from Morris on the question of the machine..Furthermore, the legacy of Kelmscott, as taken up by the private presses, had, there, become ossified in the cult of the ‘book beautiful’ or had degenerated in weak imitations of the original conception. The advent of Art Nouveau, and its degeneration, had brought further confusion, especially to a trade printer trying to keep up with fashion. In the face of this situation of decline, the compromise made by the reformers was to accept the machine and provide it with good typefaces. For the book-centred reformers, ‘the machine’ meant above all the Lanston Monotype composing machine, which in Britain was dominant in the sphere of book-printing; line-compos- ing machines predominated in newspaper production..

Kinross was right in pointing out that the task of printing books had gone beyond the scope of the printer and, by the twentieth-century had to become part of the work of designers. The newness of the emerging field can be traced by the uncertain nomenclatures surrounding a new need that no one knew how to name. “The post-war reformation was to be largely the creation of such ‘advisers’, bringing to the printing trade the elements of design. ‘Design’, that is, both in the sense of an aesthetic awareness and in the sense of rational coordination of production,” Kinross stated.“The difference was between the merely modern, seen against a backward trade or ossified bibliophile context, and the consciously modern or the modernist.” In other words, in England and in Germany, the old tradition of hand lettering, which had been replicated in old fonts, was being replaced by a rather belated admission of the role of the machine in printing. The hand had to be banished. By the early twentieth century, another element was presenting itself: the role of typeface in presenting what we would term today as “branding.” In other words, there were some products or services that were difficult to present visually, such as the London Underground.

The massive subway system needed to be united by more than rails under the Underground Group. As Oliver Wainwright explained in The Guardian, the subways, plural, were united into one, under a single “brand,” and in 1916, a calligrapher Edward Johnston (1872-1944) was asked by Frank Pick, head of the Group, to create a typeface that was modern, distinct and yet unobtrusive. The result was a font that was based on the sharp-edged lettering on Trajan’s column, the capitals the artist considered “held the supreme place among letters for readableness and beauty,” as “the best forms for the grandest and most important inscriptions.” The stripped down, lightweight and legible capital letters were san serif, something a bit new in the early twentieth century. In his article, “London to the Letter: Meet Edward Johnston, The Font of All Tube Style,” Wainwright credits Johnston for drawing attention to the way in which such clear and clean fonts could be read with ease. The London Underground script, as it is known today, seems to lift and fly with the speed of the cars rushing past, a prime example of a brand fitting the function of what it represents. One hundred years later, this font is still timeless and irreplaceable–just like Trajan’s column.

Johnston had a close associate, the younger designer Eric Gill (1882-1940) who was inspired by the trim look of the sans serif font to create his own font, known as Gill Sans, in 1928. A bit thicker than Johnston’s Underground lettering, Gill Sans is one of the best-known fonts today and was recently redone in 2015 for the contemporary eye, redesigned as the Gill Sans Nova and the Joanna Nova series. As the owner of these fonts, the Monotype corporation explained, “These are contemporary digital typefaces – with a wide range of weights, alternate characters, and extended language support – that pay homage to Gill’s original designs.” The creative director of Monotype, James Fooks-Bale, said, “The Eric Gill Series is what I’d like to refer to as a living narrative, not static and we’re a small part in its evolution since the 1920s.” Like Johnston, Gill’s font would become part of English transportation when Gill Sans was adopted by “London & North Eastern Railway in 1929 as its official typeface for publicity and posters, later appearing on trains themselves. Then Gill Sans really spread its wings, because at nationalisation in 1948 it was adopted by the British Railways Board for its station signage, rolling stock lettering, timetables, and publicity.”

As a 2013 article at UK Time explained, “The British Railways station signs worked so well because Gill Sans is a very dictatorial font, ordering you about in a no-nonsense way. As such, the signs were perfectly suited to the post-war period in Britain, the last time that men in bowler hats were in charge of everything before the 1960s came along and the whole structure of society was blown apart. How reassuring it must have been for a train traveller of the 1950s to know that when arriving at Barnstaple, or looking for the Way Out, they could be in no doubt at all that they were indisputably at Barnstaple, or the Way Out would be precisely where indicated.” Gill Sans was used until the British Railways were privitized in 1965 and Gill’s work was replaced by the Rail Alphabet.

British Railway Car with Gill Sans signage

In Just My Type: A Book About Fonts, Simon Garfield wrote, “Oddly enough, Gill Sans is itself a curiously sexless font..In his autobiography, Gill explained that sans serif was the obvious choice when ‘a forward-minded bookseller of Bristol asked me to paint his shop fascia.’ The long wooden sign in question, for Douglas Cleverdon, led to something else–after seeing a sketch of these letters, Gill’s old friend Stanley Morison commissioned him to design an original sans face for Monotype. Its impact was instant and is still reverberating..It was the most British of types, not only in its appearance (spare, proper, and reservedly proud), but also in its usage, adopted by the Church of England, the BBC, the first Penguin book jackets and British Railways (where it was used on everything from timetables to restaurant menus). Each showed Gill Sans to be a supremely workable text face, carefully structured for mass production.It wasn’t the most charming or radiant, and not perhaps the most endearing choice for literary fiction, but it was ideal for catalogues and academia. It was an inherently trustworthy font, never fussy, consistently practical.” However, to return to the beginning of this paragraph, why did Garfield use the unexpected phrase, “oddly enough” to comment on the sexlessness of Gill Sans?

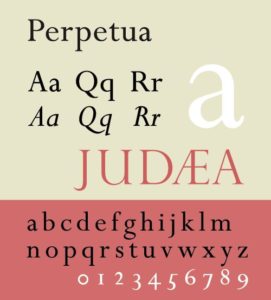

Perpetua, unlike Gill Sans, has serifs

The great design historian, Steven Heller, reported for Wired Magazine that Gill wrote about his penchant for bestiality and incest and produced pornography, even while designing the Perpetua font, in his diary. The combination of creating elegant fonts and exotic sexual tendencies, which, as the author observed wryly, earned “him posthumous scorn.” The author of the biography, Eric Gill: A Lover’s Quest for Art and God, that revealed Gill’s most interesting life, Fiona MacCarthy, considered the link between the artist’s work and the artist’s personal life: should one be judged by the other? For her article in The Guardian, she discussed a less known aspect of this work, his sculpture. Gill was as adventurous in his public sculpture as he was in his personal life. By 1910, a decorous time in the British arts, the sculptor and soon to be famous font designer, was exploring forbidden topics and producing heretofore rare subject matter. As MacCarthy wrote,

He was already working at the extremes of the domestic and the risqué; his placid mother and child carvings contrasting with the sheer effrontery of such works as Votes for Women, an explicit carving showing the act of intercourse, woman of course on top. Maynard Keynes bought the carving for £5. When asked how his staff reacted to it, he replied: “My staff are trained not to believe their eyes.” This was also the period at which Gill was making the almost life-size sculpture he entitled Fucking. This carving was over protectively rechristened Ecstasy when bought for the collection at Tate Britain, having been discovered abandoned in a boathouse at Birchington-on-Sea. Is it relevant or is it a distraction to know that the subject of the carving is Gill’s younger sister Gladys and her husband Ernest Laughton, entwined in a position of – well – ecstasy, and that Gill’s own incestuous relationship with Gladys was then in progress, continuing for most of their adult life? To me it is significant in stressing the artist’s dependence on the known and familial: his passion was the personal, he would not use outside models. It certainly deepens understanding of the element of voyeurism in Gill’s work.

The biographer’s 2006 article, “Written in Stone,” discussed Gill’s fonts only briefly, but mentioned that, during 1924, he created the Gill Sans series in a “ruined Benedictine monastery at Capel-y-ffin in the Black Mountains of Wales. Here he designed his brilliantly workmanlike typefaces for Monotype, typically throwing his reservations about machine production to the winds. Gill Sans, the sans serif typeface used on the covers of pre-war Penguin books, is rightly lauded in the current V&A Modernism exhibition as the first British modernist type design. What is striking,” MacCarthy wrote, “is that once the immediate commotion over Gill’s sexual aberrations had died down, there was a new surge of interest in his work.” in fact, the reissue of an updated version of Gill Sans, took place ten years later. Like the recent renovation of Gill Sans, the Underground font was also slightly altered. As the London Transport Museum reported, “In the 1970s, London Transport looked into the suitability of using Johnston or its replacement with a more modern letter form. In 1979, Eiichi Kono, a young Japanese designer working for Banks and Miles, revised the original Johnston with slight changes to the proportions to some of the letters and created bold and italic fonts. The New Johnston type is still in use across the network today.” Whatever one might think of Gill the man, it is clear that he followed the creed of his mentor, Johnston, that a font should demonstrate “Readableness, Beauty, and Character.”

But, for the purposes of this series, the question must be asked, why raise the issue of the artist’s life and Gill’s work in fonts? On one hand, there is an interesting contrast between the straightforward Gill Sans and the tangled life of the artist, but, on the other hand, the disturbance about his character underlines how important fonts are to our lives today. For German artists, fonts became deciding factors in their lives. At the same time, Eric Gill was working on his sans fonts in a remote monastery, his German counterparts were creating letters that would put their lives at risk. The next post will examine the dangers of making fonts for the wrong person–Adolf Hitler–at the wrong time.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.