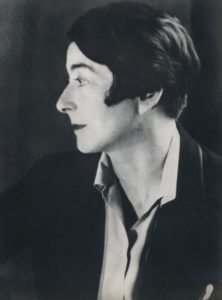

Eileen Gray (1878-1956)

Art Deco Furniture Design, Part Two

The story of Eileen Gray, who vanished from history, leaving behind some of the most famous and iconic designs of the early twentieth century, is a strange one. She possessed many names, Kathleen Eileen Moray Gray, but used only two. Marked by fame, followed by erasure, this Irish designer shifted from Ireland, her home country, to England, to Paris, back to London during the Great War, and finally back to her expatriate life in Paris. Unlike the British Isles, Paris was the best city for an ambitious designer and one of the few cities open-minded enough to support a business run by a woman. Although Gray worked with several men, she was not overshadowed by them nor, on the other hand, was she connected to a fellow artist. Therefore, unlike Sonia Delaunay, for example, there was no masculine fame to connect her to art history and gradually, she slipped from view, barely living long enough to be rediscovered. And yet, in her own time, Gray, like Delaunay, was a success, running her own business and designing for the wealthy and famous. The peak of her career was the decade before the Great War and the decade after the War, the period when she transitioned back and forth between design and architecture. By the 1930s, Gray was beginning her withdrawal from a world where she once led in innovation. Her furniture was left behind, part of elegant homes of the famous, and it was the fame of the clients that assured the survival of the art of Eileen Gray.

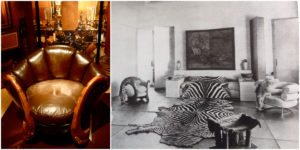

One of her early clients was Madame Mathieu Lévy, who designed the “Suzanne Talbot” line of couture dresses, hats, and other accessories. Today Lévy’s name is rarely uttered, and her work is displayed under “Suzanne Talbot,” a brand connected more to hat designs in the 1920s, she was one of the best-known couturiers of her time. Like Eileen Gray, the fashion designer was very interested in non-European cultures and her objects and clothing were difficult to “place” in fashion history. Madame Mathieu Lévy’s work was not obviously Art Deco in that it was not connected to late Cubism, but, in common with some aspects of Art Deco, her response to the culture of the twenties was one of global eclecticism. Ironically, like Gray, history has left Lévy stranded, and today she is one of the lesser known designers. But, in her own time, Lévy was among the numerous famous female designers of the years before the Second World War. She commissioned Gray, who also did not quite fit into a precise slot, to furnish her apartment on rue de Lotta. Because Gray designed labor intensive lacquer pieces for the apartment, this project took several years, with various sources citing periods from 1917 to 1921 or from 1919 to 1922. The time period of the commission was an unexpectedly fraught one, for a disruptive war would change the world of design from one of handcraft and art to one of industrial design, making it a challenge for Gray to fulfill the client’s brief: to make the apartment as up to date, as modern, as cutting edge as possible.

Today the most famous of her early hand-made works for Lévy is the Dragons Chair (Fauteuil aux Dragons) that dates from 1917 or 1919. The Dragons (or Dragon) chair took two years to craft. This small chair was only twenty-four inches tall and, when the brown leather chair came up for auction, Christie’s described it as “small.” Once owned by Yves St.-Laurent and sold from his estate for $28 million, the arms of the Dragons armchair are a pair of carved and spotted wooden snakes which wind around and become the feet of the chair. Christie’s described the complicated and unique chair: “In the form of unfurling petals, upholstered in brown leather, the frame in sculpted wood, lacquered brownish orange and silver and modelled as the serpentine, intertwined bodies of two dragons, their eyes in black lacquer on a white ground, their bodies decorated in low relief with stylised clouds.” The Dragons Chair had an equally unexpected companion: a dug-out canoe, its exterior lacquered in brown and its interior covered in silver leaf, repurposed into a day bed standing on twelve pointy feet. This Pirogue sofa bed, created after the Great War was made of brown lacquer with a tortoise shell overlay. The animal-like bed made sense of the arms of the Dragons Chair which were also brown lacquer, animalistic in that the arms wound themselves up and down the sides of the chair, becoming its legs. These very special pieces of furniture were homage to the client’s interest in Tribal Art in Africa, and frequently the so-called Dragons Chair is called the Serpents Chair. But during and immediately afer the War, the art scene shifted decisively. Gray had returned to England in 1915 to serve her nation and she had come into contact with the waning movement of Vorticism. Dedicated to machines and asserting the primacy of the British claim to the Industrial Revolution, Vorticism was a preview of the post-war machine aesthetic.

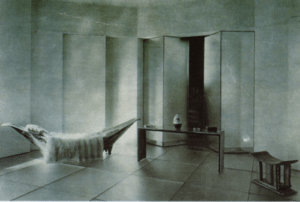

The dedication to handwork and the insistence of Eileen Gray that household furnishings could be works of art changed after the Great War. Once the fighting stopped and the Treaty of Versailles was finally concluded, the international arts community regained contact with one another and the ideas of the new Russian Avant-garde and the Dutch De Stijl, not to mention the new German movement of the Bauhaus, began to circulate. Although Eileen Gray altered her aesthetic completely, the change was gradual. In 1922, she opened her own shop to show her own unique products. The elegant store, named Jean Désert was optimally located in the fashionable street, Rue )Fauborg Saint Honoré. At the 14th Salon des Artistes Décorateurs in 1923, Gray unveiled an entire room, a boudoir, with walls, ceiling, and sets of folding screens covered in white lacquer. The canoe daybed reappeared, complete with a fur throw for a texture contrast, placed near a long low table bearing ornaments and, on the other side of the room, a low carved wooden stool, called a “console,” with a concave seat that played off, curve for curve, with the swooping day bed. All three pieces of furniture appear to be floating on a white floor as if Gray had created a dream taking place in a cloud. By the mid-twenties, we see a fully mature artist not only changing her style but also hitting her creative stride.

Interior of Gray’s Rue de Bonaparte apartment

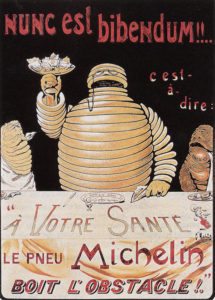

At this point, Gray was still making her lacquer designs but she was also transitioning to the new technology of bent stainless steel. In the photograph of the Lévy apartment, the new modern post-war chair was on right side the fireplace, opposite the Dragons Chair and the size difference is apparent. Making furniture by hand with laborious craft techniques is easier on a small scale while putting together a manufactured elements meant that the chair could be significantly bigger. In 2014 Richard Storer-Adam explained the origins of one of Gray’s early industrial pieces of furniture, the Bibendum Chair. He wrote, “The Chair’s back and armrests consists of two semi-circular, padded tubes encased in soft, black leather. The name that Gray chose for the chair, Bibendum, originates from the character created by Michelin to sell tires. The Michelin Man is called “Bibendum”, a word taken from the slogan “Nunc est bibendum” meaning “Now is the time to drink”. In this particular case, to “drink”, or absorb, bumps and obstacles found on the road. He was originally shown depicting bicycle tires, so he looked quite mummy-like.”

Marius Rosillion. The original Michelin Man (1898)

The author continued, “The frame of the Bibendum Chair, including the legs, are made of a polished, chromium plated, stainless steel tube. Stainless tube was a new highly innovative material. The first stainless steel was created in 1913 by Harry Brearley who created a steel with 12.8% chromium and 0.24% carbon.” The fact that Gray had created a chair designed from bent steel tubing in 1926 puts her chair squarely into the time period when Marcel Breuer and Mies van der Rohr were designing their tubular steel chairs, between 1926 and 1927. The Bibendum Chair is dated 1926, and yet Gray’s design is usually left out of the histories of modern chairs. Perhaps the two plump enveloping rings, stacked half-circles framing the round equally comfortably padded seat, was simply too comfortable. Chairs by Mies and Breuer were stunning to look at, but, like the famous Red and Blue chair of Gerrit Rietveld, were hard to sit in. The platform of the chair, which does not have the traditional legs, is another version of the E.1027 side table: two verticles resting on a half circle.

The E. 1027 house, which will be discussed in the next post, was an important site for Gray’s post-war chrome, glass and lacquer furniture that is multi-purpose and adjustable in ways that was unique in modern furnishings. The beautiful and spare Rivoli tea table of 1928 is a case in point. While Gray’s chairs are perhaps better known, this tea table allows us to view Gray’s work in its own right, without reverting to the inevitable and diminishing comparisons to Mies or Rietveld. The tea table, designed for her own home, was imagined from the point of view of functionality as the starting point for the components. The components or the elements of the table were then stripped down the bare minimum necessities, free of decoration and of opulence or of craft. Imagine the table as a drawing, a blueprint, with the ruled lines being transformed into a chrome structure that could slide to open wider or slide to become more compact. These are the verticals and horizontals but, in a move, now familiar in Gray designs, she imposed contrasting circles, in this case. two round serving trays mounted on rotating arms at two levels, so that those standing and those sitting could reach over and retrieve a tea sandwich or a petit-four. The Eileen Gray website that sells her furniture today described the tea cart in its alternative function, as a “Small dressing table. Polished chromium plated tubular steel frame. Cabinet fitted with two pivoting drawers and one hinged door. Top and cabinet in high gloss lacquer in various colours..Eileen Gray decided to have a special table to serve her guests tea in her new house E1027. She wanted to do this ‘elegantly while standing; serving tea sifting at a low table is rather awkward’; while at the same time displaying the cakes, tartes or fruits in an ‘interesting way.'” When folded in half, the lacquer panels of the table drop down and form what is now called a “waterfall” effect with the top lacquer panel. Few modern designers thought in terms of function in the sense of actual functionality. In other words, since, Louis Sullivan said, “Form ever follows function,” form has always come first, with function, as its supposed impetus, following along behind. Gray reversed the formula and based her form upon her own experience as a user–this is the kind of table she needed. The tea table could serve in a bedroom as a dressing table, in a bathroom as a toiletries table or in a living room to serve tea. It could be as accommodating or as compact as the room or the occasion demanded. The main surface was obviously for the tea service and the adjacent narrower surface was for the food. The host could preside over the table or s/he could let guests help themselves. Louis Sullivan’s assistant, Frank Lloyd Wright, in contrast, would fix furniture to the floor so the owners could not disturb his placement. Gray invited the client to invent uses for her designs, which are statements of functional modernity.

As was noted, the laborious hand-made art objects that were one of a kind gave way over time to the machine moderne of the 1920s, but her penchant for repeating shapes continued for the furniture she designed for mass production. But as shall be noted, Gray did not share the adherence to architectural theory or modernist philosophy that drove her male colleagues. She used standard geometric shapes that were universal, like the radical architects, but her thought processes were quite different. It is possible to conjecture that Gray’s decade-long experience in working with individual clients and responding to their needs gave her a very different understanding of the role of modern design in a machine age. Her new post-war products were sold out of her own store, Jean Désert, named after an invisible male who supposedly was the owner and desert because Gray admired North African landscapes. However, in her old age, Gray gave Zeev Aram, of the Aram Store in London to reproduce her furniture. The authorized editions of the table are always manufactured in chromium plated steel tube and always have a signature stamp and an identification number. Both the chair and the table can be seen in the newly restored E. 1027 home, completed in 1929 and, after decades of vandalism, was brought back to its original condition in 2015. The next post will discuss this re-discovered architectural masterpiece.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.