Controlling Women In Italy

Designing Submission, Part One

Any authoritarian regime, of any age, regardless of location on the globe will move immediately to control the uncontrollable: women. The first step is always to take away as many of the pre-given rights granted to women as possible, whether, in the modern era, could be the right to vote or the right to control her own body. The second step is to disenfranchise women and to push them out of public life, removing them from jobs, taking away their independence and then placing them back in the domestic realm and under the rule of their husbands, fathers and brothers. But there is a third element that immediately arises from the first two steps taken by authoritarian states–women separated from society are women who have no stake in that society. Stripped of the right of expression and barred from creating their own cultural expressions, women are reduced to muteness and, without being allowed to participate in public life, they have no interest in supporting that which has excluded them. In other words, the State has created an enemy inside the gates. The famous painting by Jacques-Louis David, Le Serment des Horaces (1784) makes a compositionally clear divide between the men and the women.

Jacques-Louis David, Le Serment des Horaces (1784)

The black Tuscan column on the right acts as a signifier stressing that the upright phallically enabled males aggressively occupy two-thirds of the painting. Their swollen and straight-lined ridigity contrast with sloping and limp lines of the women who are without phallic glory and have hence been relegated to the marginalized positions of wife and mother and sister. As the bearers of the young, women went beyond their prescribed roles, that of childbearing, and became attached to the children they raised, came to love their husbands and brothers. Contrasted to the red-cloaked father at the center of the painting, a father who freely sends his sons to their deaths, the women, invested in their emotional attachments, weep and mourn the losses sure to come. The surviving son of the triplets of the Horatii returned home only to slay his own sister who had the misfortune of being betrothed to a son of the enemy family, the Curiatii. The values of the males clearly do not include love or loyalty of compassion–such “virtues” cause weakness and, in a warrior culture, men had to be strong and overcome inconvenient sentimentality.

Le Serment des Horaces, a tale from early Republican Rome, is an interesting work of art when considered in the context of Italian fascist culture in the 1920s. Like ancient Rome, modern Italy had become or at least aspired to be a militaristic culture, preparing for war with the aim of rebuilding an empire. When Benito Mussolini (1883-1945) came to power as a young prime minister in 1922 under the definition of the modern dictator: “a man who is ruthless and energetic enough to make a clean sweep,” his intentions were to put himself and the fascist party in power–the “ruthless and energetic” part and to remove the troubling elements of socialism and Communism causing unrest in Italy–the “clean sweep” element. However, Mussolini, a former anti-war socialist himself, kept the traditional trappings of the Italian establishment, the King Victor Emmanuel III and the Church in place, albeit bent to his ends. Although Mussolini, in his youth had not been a friend of the Catholic Church, in fact, his was nicknamed the “priest eater,” the Vatican was in Rome and religion was a powerful unifying force, transcending politics. The Pope Pius XI cast a wary eye on Mussolini remarking, “if there is a totalitarian regime – in fact and by right – it is the regime of the church, because man belongs totally to the church.” However, the Pope allowed himself and the Church to be co-opted by Mussolini, linking religion to fascism in ways that would later compromise the legacies of two Popes. In her interesting article on the relationship between the Church and State in Italy, Lucy Hughes-Hallett wrote that Mussolini concluded that “It was easy to manipulate the church, he told his new allies in Nazi Germany. With a few tax concessions, and free railway tickets for the clergy, he boasted, he had got the Vatican so snugly in his pocket it had even declared his genocidal invasion of Abyssinia ‘a holy war.'” In fact, the fascists designed rituals reminiscent of ecclesiastical ceremonies and appropriated the aura of the sacred to their own cause. For the faithful of Italy, it was therefore easy to slip between the sacred cause of Il Duce and devotion to religion.

For Mussolini, the union with the Church brought him an unexpected ally in his struggle to control women and their ideas of “emancipation.” But Il Duce faced an unprecedented problem. No other dictator had to deal with an entire population of women liberated by their independent role in Great War, out from under the shadows of men. No other authoritarian ruler had to contend with young women who were enjoying the rewards of new standards of morality which had drifted down from France, not to mention the sweeping changes in fashion–skirts half as long as they had been, short cropped hair and colorful makeup, not to mention smoking and drinking and driving. As David’s painting suggested, in France, even under a Revolution in 1789, social change would never include women. In the early nineteenth century, it was easy enough for Napoléon I to strip women of whatever rights they thought they deserved after the Revolution and put them back in their place. One hundred years later, Mussolini was faced with a population of women out of control, who needed to be put in the service of the State. The Pope would be invaluable in lending the opinion of religious teachings to suppress women. In her review of The Pope and Mussolini: The Secret History of Pius XI and the Rise of Fascism in Europe by David I. Kertzer, Lucy Hughes-Hallett noted that the Pope Pius “fretted over inadequately dressed women – backless ballgowns and the skimpy outfits of female gymnasts were particularly worrisome. Mussolini played along, solemnly declaring that, in future, girls’ gym lessons would be designed only to make them fit mothers of fascist sons. He was accommodating in aiding the Pope’s war on heresy – banning Protestant books and journals on demand.”

Both Chuch and State wanted the woman of the Jazz Age, wearing Chanel outfits, and asserting herself in public settings to be reigned in. In fact, in her 2015 book The Crisis-Woman: Body Politics and the Modern Woman in Fascist Italy, Natasha V. Chang stated that the modern woman far from being admired by the Fascist and religious rulers had a name, “donna-crisi.” This “crisis woman” was, according to Chang, “in the fascist imagination a dangerous type of well-to-do modern woman with an extremely thin and consequently sterile body that purportedly confirmed her cosmopolitan, non-domestic, non-maternal, and non-fascist interests..the crisis-woman was neither gentleman nor lady–that is neither male nor female but an incomprehensible third sex. In fascist Italy, the thinness and sterility of the crisis-woman were viewed as a deviant masculinization of the naturally curvaceous and fertile female body.” The negative donna-crisi was the counterpart of the positive donna-madre, a traditional female figure, not from the city, site of all things artificial and cosmopolitan, but from the very soil of Italy itself, the countryside. Donna-madre was full hipped and full breasted, an image of fertility with her pink-cheeked plump face. However, as with all “sweeping changes,” revolutions always attract women who hope to find a new point of view and longed for gender equality. As Gigliola Gori wrote in her book, Italian Fascism and the Female Body: Sport, Submissive Women and Strong Mothers, “The Fascist regime dressed the female members of its organizations in appropriate and fashionable clothes. In the years 1926-29, for example, members of the Piccole Italiane and the Giovani Italiane, then controlled by the Fasci Femminili, wore black short skirts, black ties, and long straight white blouses that made their hips and breasts look small, and their hair, cut à la garçonne, was held away from their eyes with colored ribbons.”

Gruppo di Piccole Italiane della GI

The hopes of women that Fascism would be truly revolutionary and forward thinking towards them were quickly dashed. Revolution in politics was one thing, but a revolution in gender roles was an entirely different prospect, especially when women seemed to put men in a secondary place in their lives, living independently and delaying motherhood, a situation almost guaranteed to reduce women’s ability to be free. Therefore, once in power, Fascism had to determine exactly what to do with these women, what kind of roles they would have in society and what they should wear while performing their tasks. Their decision was to be reactionary and to drag women back to their traditional positions. As the article “Contrasting Image of Italian Women Under Fascism in the 1930’s” by Jennifer Linda Monti pointed out, “Although a “revolutionary” movement, Fascism still maintained strong and traditional beliefs, especially with regard to the role that women played within their families and society. While attempting to modernize Italian society, Italian culture and Italian fashion, Mussolini also wanted women to remain in the traditional role of mother and wife, central to the nuclear Italian family.” For years, Italian women had been caught between the repressive dictates of the Church and the oblivious isms that followed the war, from socialism to fascism. As Monti continued, “During the Socialist and Fascist years as well women were never granted the suffrage and political power they were promised. Socialism was more concerned with class issues, rather than gender, and Fascism, although promising female suffrage during its first years, quickly revoked the promise after 1925, when the dictatorship was established, and when Fascism created the title of podestà in all Italian cities.” The podestà would, of course, be male.

A parade of the Giovani Italiene, a fascist organization for young women Italy (1935)

Far more than in other European nations, women in Italy had been marginalized and repressed for centuries had no protection from the government unless one was a prostitute and then the state would be in charge of the body in the service to the male. The Lega Promotrice degli Interessi Femminili, organized by educated women, was established in 1880 but concerned itself with middle and upper-class women only, and, much like the feminist movement of the 1970s, paid less attention to rural and/or lower class women. Although the experiences women of all classes had during the Great War changed the way they led their lives and altered the way they thought of themselves as women, the men in power regarded their brief independence as an aberration and were intent on pushing their wives, mothers, and daughters back where they belonged, subservient to the male. Ignoring the contradiction between being a “revolution” that would sweep the past away, Fascism, like Futurism, took a dim view of women and Mussolini declared that women should be “submissive women and strong mothers” like the strong peasant women of the countryside, simple, modestly dressed, and hard-working. However, inspired by American films, foreign fashions, and lives more interesting without men, many Italian women ignored Mussolini’s desire that they dress like peasant women from the farms. Urban women read Parisian fashion magazines, and, as the 2009 book, Fashion at the Time of Fascism: Italian Modernist Lifestyle, 1922-1943 by Mario Lupano and Alessandra Vaccari pointed out, women of all classes had access to a thriving industry of patterns and sewing machines. When they sat down at these machines, Italian women who couldn’t afford to go to Paris and shop–like Mussolini’s daughter–were copying the outfits they saw in magazines, not those costumes worn by the peasant women.

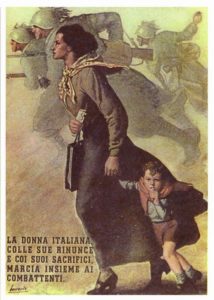

The war-time poster shows the idea Italian woman, modestly dressed, with a child in tow.

In 1925, hoping to inspire these reluctant women to their higher calling, Mussolini announced the “Battle for Births” or support for motherhood by the state under the auspices of the ONMI (National Organisation for Maternity and Infants). Supposedly an economic plan to encourage marriage and parenthood, the overall policy included taxing unmarried men, making it harder for women to obtain birth control and abortions. By 1927, expressing his desire to increase the birth rate, Il Duce provided financial incentives to have children and increased restrictions on divorce. Mussolini, with the coming war in the back of his mind, wanted to increase the population of Italy by twenty million people. That figure meant that somehow millions of women had to be convinced to have children they neither wanted or could afford. Although the entire nation was encouraged to celebrate Giornata della madre e del fanciullo–mother and child day–on December 24 and women with seven children were given financial rewards by the state, few women seem to have been inspired to go through multiple childbirths. Despite his best efforts, the goals of Mussolini did not seem to impress women, who continued to marry later, continue to be active in the workforce, and have fewer children.

Both Mussolini and the Church took a dim view of women who were, they believed, inferior to men in every way. On one hand, women should be dismissed as Mussolini said, “women are angels or demons, born to take care of the household, bear children, and to make cuckolds…” but on the other, they needed to be contained. In 1930, alarmed by out of control women, still not submitting properly to Fascism, Pope Pius XI issued the papal encyclical, Casti Conubi, reaffirming the rule of the male at home. The State joined in with efforts–during the Depression years–to keep half its productive labor force–women–out of the job market. Clearly, neither the Fascist regime nor the Catholic Church had practical ends in mind, such as improving the economic condition of Italy, in mind. Their mindset of misogyny and the general dislike of women, who were so difficult to control, by authoritarian elements overwhelmed any of the practicalities of building the strength of the new empire through full employment of women. Alarmed at the new thin women who were constantly dieting, the Fascist regime tried to re-educate the Italian woman on the desired shape of her new fascist body. Gori noted that Mussolini liked “feminine fat and encouraged physicians to convince women patients, especially those living in cities and therefore more likely to be in touch with dangerous foreign fashions, that slimness was unhealthy while being comfortably heavy was a sign of good health.” Efforts were made to stamp out images of fashionable women and Hollywood movie stars, but once again, there were internal contradictions. The regime also wanted women to be athletically fit and healthy. The Opera Nazionale Balilla was a huge and immersive Fascist youth organization, set up in 1926, with the aim of indoctrinating boys from the age of six into Fascist thinking and ideology. There were corresponding organizations for little girls, educating them in feminine pursuits of motherhood rather than readying them for a military future.

Mussolini was fighting against a tide of women’s aspirations he could not control. One of the obstacles in his desire to reshape Italian society in the image of fascism was the fact that Italy itself was multiple societies, practicing different cultural and social practices, a holdover from the ancient Italian city-states. Another obstacle was the division between the industrial north and the rural south, not to mention the gulf between the cities and the countryside. Fascism could only overlay like a skim these traditional divisions. Mussolini wanted to elevate all Italians out of “backwardness” but traditional societies fit in rather well into his own regressive attitudes towards women. But the dictator stressed modernism, a twentieth-century reality to be expressed militarily and socially but a modernity that also refused to grant women equality or a place in the world. Through a multitude of fascist organizations, women from all over Italy were gathered together, more or less willingly, to serve the cause of fascism. The 2011 article by Monti has an excellent discussion of the fascist efforts to control women through organizing them, but, in an interesting twist, Mussolini’s endless list of activities for women had the effect of bringing woman out of the isolation that the domestic home had imposed upon them, allowing women to come together on a mass scale for the first time in modern history.

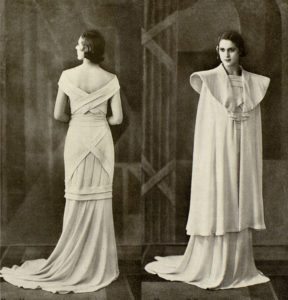

Haute Couture Fashion in Fascist Italy

Despite all of Mussolini’s efforts to remake the Fascist woman into his image, the fashion industry itself, a thriving enterprise in an otherwise poor nation, constantly subverted fascism. No matter how chic the black and white uniforms for Fascist women, the enforced conformity was offset by statements of individuality made through fashion. The next post will discuss one of the most famous Italian fashion designers whose fame and individuality seemed to push Fascist to the background.