Adolf Loos

Experimental Architecture and the Question of Windows

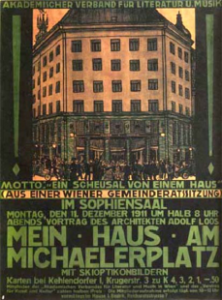

Before the Great War, Vienna was the city of Otto Wagner, and Loos would have to wait a decade before he would be allowed to build to his own standard of “purity” or lack of inauthentic decoration. Like Wagner, Adolf Loos (1870-1933) wrote a great deal before he could bring his theory and his actual architecture together. However, unlike Wagner, Loos was not embedded in mainstream Imperial culture but was part of the avant-garde. As a result, he had a bit more freedom. For one shining moment, he was given an opportunity—a chance to materialize his theories—that resulted in scandal and city wide ridicule. In 1910, the city of Vienna was horrified by the radical design on Michaelerplatz, a project Loos designed for Goldman & Salatsch, a firm dedicated to clothing fashion conscious men. In “Ornament and Materiality in the Work of Adolf Loos,” Brian Andrews discussed the wide range of materials, even luxury materials, used by Loos on this public facing building.

The Looshaus on the Michaelerplatz was another project where Loos used marble in an ornamental fashion. He used Skyros marble in the interiors in the same way that he used it on the exterior pillars of the Karntner Bar; as a graphic device. On the base of the exterior façade, Loos employed Cipollino marble in a different manner and as a direct reference to Rome. The Romans had made extensive use of this marble and Loos attempted to draw a connection to the Romans by using this marble and also by using classical forms. Since Loos rejected the ornament of the 19th century that was so prevalent in Vienna, he was again facing a design dilemma; how was he going to dress the bottom of this building in a way that worked with its consumer function. Loos, having spent time in Chicago, was very aware of the ornamentation that Sullivan had used as an attention getting device in the Carson Pirie Scott building. He realized that something similar would be required in the Looshaus. Loos chose a marble that on one hand was as graphic as Sullivan’s ornament, and on another connected the building directly to Rome and Roman Culture. Essentially, by embracing historical forms and materials, Loos was able to leap over the problems of new invented ornament.

Looshaus, Michaelerplatz 3

By 1910, Loos had been pondering the very concept of architecture and was considering the possibility that a work of architecture could also be a work of art. Indeed, it can be said that the Michaelerplatz building was a unique creation, sitting in an open site, served up like a sculpture on a pedestal, begging the question of artistry. Perhaps those who had been following the past twelves years of Loos literature, the sudden statement that a building was just a building and not a work of art might not have been a complete surprise but to the general public that walked through Michaelerplatz every day, the place of business was strange indeed. But what alarmed the spectators was not the presence of art but the absence of ornament. Without ornament how could a building be art? At this point, Vienna is in the grips of Art Nouveau which is the very definition beautiful ornament and elegant decoration. In 1910, the exuberant exterior of Otto Wagner’s Majolikahaus seemed like an elegant solution to the long standing problem of historicism. But Loos could not consider the compromise to be “modern,” and “Looshaus,” as the business was called, introduced to an unprepared public what a building without ornament or a completely nude structure looked like. At first the street level seems conventional enough, with its four Tuscan or Roman Doric columns suggesting an entry into a temple of tailoring. From street level, there was a comforting conventionality and even a nod to tradition. However, it was the upper sections, strikingly white—the color for modernism in the future—with three floors marked by plain unadorned windows starkly outlined in black trim that roiled the judgmental public. Loos expressed his preference for what he called “smooth and previous surfaces,” in which the structure becomes both surface and design. The unmarked plastered “smooth and previous surface” for these apartment floors of the lower public entrance were adorned with green marble and structurally useless and mockingly illogical columns, quite unlike from the consistency of the plain white private floors above.

As Joseph Masheck wrote in his book, Adolf Loos: The Art of Architecture, “Purportedly, it was the shamelessly unadorned simplicity, as if undressed, of the unrelieved, gridded fenestration of the whole upper façade that had everybody in a stir. A well-known journalistic cartoon could liken it to a flipped-up storm drain grate in the street in front of it only because, to most people, it looked ignobly lacking in bourgeois grandeur that made for serious architecture, architecture worthy of the the name. But despising historicism–the parasitic dependence on historical stylistics–is not the same as denying art history..the building has quite decent art historical ancestors in its own right..Particularly Sullivanian, however, seems the crisp, unmodulated conjunction of cylindrical-columnar and boxy-beam forms in the lower commercial part of the Looshaus, with, between the shorter bay windows of the entrance hall, each square pier between bays answering a column immediately beneath.” Masheck made case for Loss nodding to Roman roots combined with the linear arrangements of Louis Sullivan, suggesting that the building was an extended and subtle commentary on the history of architecture but using a vocabulary that would have gone over the heard of the average passerby.

Public outrage ensued and was directed especially towards the windows. In a backwards fashion, the bewildered town fathers were astute in noticing the revolutionary aspects of the windows. Once ornamentation is removed from the façade, one might ask, what is left? The answer would be windows. Loos therefore had to pay intense attention to the treatment of the overall fenestration and the placement, size, and proportion of each window became a heightened decision because, suddenly, the plain white façade was punched with a series of openings. Once surrounded by decoration, windows are now stark and naked. Now that they are freed from larger patterns, the windows can become patterns in their own right. These finer points of the newly significant role of fenestration in modern architecture was not considered by those in charge of the city. Such were the objections to this building that the construction was halted in 1910, largely due to the lack of “eyebrows” or architectural embellishments for the tops of the windows. Loos was forced to compromise and added bronze window boxes so that the steel and concrete building could be completed in 1912. The metal rectangles bursting with flowers were placed below and not above the windows, a stubborn gesture that did not go unnoticed by the ancient Emperor Franz Joseph, who, due to an astonishing lack of zoning in Vienna, lived across the street in his Hofburg palace. The old man refused to look at the ugly house, used a rear entrance to enter and exit the palace, and closed the curtains of the windows that overlooked the establishment of bespoke suits. In truth the windows, those that can be appreciated without the interference of the flower boxes are simple and symmetrically elegant: three vertical panes topped by a horizontal lintel capping the glass “columns,” each pane of the same size. The lightness of the overall structure is give a necessary weight by the dark recess at the top of each window. Today the building, flower boxes and all, is called the Looshaus, its distinctive upper stories predicting a century of modernist architecture to come—no window boxes, just the smooth white surfaces of a purified structure, stripped of unnecessary ornamentation.

After thirteen years of lecturing and writing, Loos had finally acquired a major commission, but he would have to wait for the final development of his theories, which he would realize in a series of groundbreaking houses. According to Panayotis Tournikiotis, this Looshaus was placed in a site that included Saint Michael’s Church, which had a classical façade, the entry to the imperial palace that served the court of honor, designed in the 19th century by Fischer von Erlach, the Herberstein mansion, three middle class homes. With these surroundings, the author stated that “It symbolized the meeting of the medieval town and the modern city, and the meeting of memory and of creation. Loos intended to create a building well integrated with the urban fabric.” The biographer quoted a letter the architect wrote “The House that Faces the Hofburg,” stating, that he had “..conceived the house in such a manner that it would be integrated as such as possible into the plaza. I derived my cornice lines form those of the church.” In explaining the design of this business establishment, Loos continued, stating that he wanted to integrate the clothing establishment with the Medieval St. Michael’s church and the Emperor’s palace with his design. “I derived my cornice lines form those of the church,” he wrote and said that the infamous windows were designed to allow the maximum of air and light to pass through. His intentions were to be harmonious, deferring to history, and to be practical within the new modernist credo which stressed functionalism. In point of fact, what he set up was the demarcation between the past and the future, igniting an intense dialogue between supporters and detractors. A war would intervene, stalling architectural modernity, but the years of delay would end with the definitive arrival of modernism in art, design, and architecture in the 1920s.