Alexander Gardner: The Last of the West

Once it was customary, in less sensitive times, to refer proudly to “winning the West,” a triumphalist trumpeting of conquest and colonialism in which “we,” the authors of history, white people, pushed into “virgin territory” (places not populated by whites), which was “penetrated” by settlers (a mild term), who brought “civilization” (death and disease) to a “vanishing race,” the “Indians” (misnamed), that had outlived its usefulness. The blank and flat prairie, once barren of proper homes and suitable crops, now bloomed under the tender care of the new inhabitants. The early family farms were punctuation marks in a sea of grass stirred by cattle ranches which stretched for miles. Hovering dangerously around the edges of this expanding tide of taming were the original inhabitants of the West, perhaps its rightful owners, indigenous tribes who attacked and burned, protesting the seizure of their ancestral lands. Linking the growing number of towns and cattle market were the railroads, the new lifeblood for the settlers. The purpose of the railroads, crawling across America, running from east to west, was to unite both ends of the nation, tying newly minted California to the old world colony of Maryland. As the railway lines pushed relentlessly forward, they presaged tide of destruction of a way of life hundreds of years old: that of the Plains Indians. Far from being the “vanishing” tribes of the collective white imagination, the Sioux and their relations were not fading not the imperial sunset but were a thriving society at its peak. The untouched beauty and freedom of this nomadic life was captured by the artist George Catlin, perhaps the last outsider to record the Native Americans before contact with European immigrants would begin to change them forever. Caitlin recorded the proud chieftains and the warriors chasing buffalo and the women working in the villages, but, within a generation, the children that the artist met would be involved in a long war for their own survival.

Bull Dance, Mandan O-kee-pa Ceremony (1832)

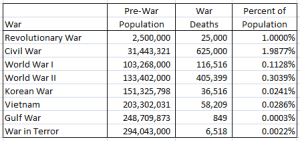

Between George Catlin and Alexander Gardner, a Civil War had raged, and its aftermath brought renewed impetus to the urge to conquer and settle the Wilderness west of the Mississippi. For idealists, America had been the New Promised Land, a supposedly virgin territory where the European who had fallen from grace could find redemption by creating, as the Puritan leader John Winthorop desired, “a City on the Hill,” a place where all actions were to be seen and viewed and judged in the name of God, a height from which no one could be invisible, or as Matthew (5:14) promised, “You are the light of the world. A city set on a hill cannot be hidden; nor does anyone light a lamp and put it under a basket, but on the lampstand, and it gives light to all who are in the house.” But the Puritanical city on the hill had known sin and after the Cain and Able conflict, it was necessary for the nation to begin again. The casualties for the Civil War are today still in contention, but the numbers remain staggering: an entire generation killed or maimed or wounded, and a future uncertain for those left behind. A 2012 BBC News report suggested that the war casualties had been undercounted by some 130, 000. Based on the research of Professor J. David Hacker of Binghamton University, the actual number, counting civilian casualties, is somewhere around 750,000. In an interview on NPR, Hacker explained that he had calculated his number from census records in terms of what was not present: the difference between the men counted in the 1860 census and the number counted in the census of 1870. But the Civil War Trust does not accept Hacker’s 2011 study, considering it too broad and all inclusive and prefers the older number of 650,000. Less important than the actual numbers is the mood of the newly United States of America which then turned to the West, toward the possibility of a new and clean start. Understanding how and why the conquest of the West turned into a bloodbath should be linked to the effects of the War upon the population that moved beyond the Mississippi. Most of the military personnel in charge of the territories during the 1870s were veterans of the War, battle hardened and schooled in the ruthless tactics suitable for modern war. Unfortunately, these attitudes were carried over and directed against an unfamiliar and ancient culture with undeniable claims on the land, a nomadic and free way of life was in the way of the needs of the nation: to renew itself. The photographer Alexander Gardner found himself standing on contested ground at the intersection of conflicting narratives, a place where another tragedy would spill out and another original sin would be added to that of slavery.

United States military casualties of war

When Alexander Gardner arrived in 1867 in what is called today the Midwest, the Kansas Pacific railroad was on its way to the Pacific coast, crossing into the lands beyond the mighty Mississippi, and the Plains tribes were being forced to concede to the white settlers and ranchers in the face of an inexorable rush towards Manifest Destiny. In the twenty-first century, it is hard to fathom the mind set of the mid-nineteenth century person, which to a more modern sensibility seems racist and sexist, leaving us with a gap where questions rather than understanding exist. What was Gardner thinking when he confronted these proud and humiliated and doomed Native Americans? Was he curious? Sympathetic? Or merely a professional doing his job, displaying normal curiosity towards new subjects? This is a man who, as a photographer, had photographed a terrible war, still among the worst events of the nation’s history, and the executions en masse of the assassins of Abraham Lincoln. We can assume that Gardner was the consummate professional and that his new commission, to follow the building of the new railway along the 35th parallel and the final negotiations for a treaty among the Sioux nations and a newly assertive America, might have well been a respite from the violence of the previous years. After years of war, railroad construction would have seemed therapeutic. The open hot windy plains, the methodical making of a straight iron path, the diligent workers, the reassuring presence of the blue uniforms and gold buttons of the military, busy with guarding forts, settlers and keeping the “natives” at bay–all of this activity signifying building and a future could have been an order, a renewal after years of chaos.

The site of Gardner’s new missions was none other than “Bleeding Kansas” itself, ironically the nexus of a whole host of dubious political concepts, from the permissibility of slavery under the doctrine of “popular sovereignty” or the right of state to decide its own political destiny, to the powerful lure of Manifest Destiny, described by the Philadelphia Public Ledger as the impetus to spread as far as “East by sunrise, West by sunset, North by the Arctic Expedition, and South as far as we darn please.” This expansion of America was to take place through or via railroads that would cut deeply into the territories of the Native Americans. Under the law pushed forward by the future opponent of Lincoln, Senator Stephen A. Douglas, the newly carved out Nebraska territory, which included the future state of Kansas, should make its own decision about slavery. From 1854 on, Kansas, which bordered on the slave state of Missouri, “bled,” as opposing factions fought over expanding slavery. This mini mid-century preview of the Civil War surprised those who assumed that the so-called Missouri Compromise of 1850 would settle the question of slavery. But the Kansas-Nebraska Act four years later poured salt on a wound widened by leaving the decision about human property to the territories and absolving the federal government of responsibility. While in retrospect, it seemed that Douglas had paved the way for the Civil War with its bloody prelude, his real motivation for organizing the western territory was to open it to railroad development with the idea that the rail line would extend to his home town of Chicago. The “right” to own slaves in the new territory was an add on, designed to increase his political popularity with the Southern states, states Douglas had to win when he ran for the presidency.

A decade later, the best laid plans of Douglas and other men lay in the ruins of the South, where in 1863 slavery ended and the Compromise unraveled. During the Civil War, which was later called “The Railroad War.”, Gardner had photographed the extensive destruction of train tracks by the Union to prevent trains from supplying the South. The conquest of the South by the federal army depended upon pulling apart its mode of transportation, and, while the photographer was in Kansas, a large project was simultaneously underway to reconstruct the destroyed rail lines in the South. Technology may be neutral but its use and disuse is never neutral; and, as William G. Thomas pointed out in The Iron Way: Railroads, the Civil War, and the Making of Modern America (2011), the great irony of the new railroads in the South was that the white population manipulated the law to restrict the movement of the former slaves on the trains and the bitter irony of the new railroads moving west was that they were designed to have the effect of making the Native Americans “vanish.” Before and after the Civil War the expansion of the railroad through the Kansas territory was fraught with fraud. The Native Americans, who ultimately signed over fifty treaties in the midwest, were robbed of their lands and their freedom, corralled onto reservations, and under a strange arrangement termed “severalty,” tribes such as the Delaware, the Kickapoo, and the Shoshone would “eventually” be allowed to control their own affairs only when the President was sure that they were “intelligent” and “prudent” enough to take care of themselves. So much for “popular sovereignty.”

The back story of the Kansas Pacific Railroad is an ugly one, but it may have given Alexander Gardner some satisfaction to witness a building project, dedicated to construction rather than destruction, and to record what seemed at the time to be a peaceful end to a dispute over land. As Jane E. Simonsen pointed out in her article “On Level Ground: Alexander Gardner’s Photographs of the Kansas Prairies,” the photographer had been hired to promote the railroad as a frank manifestation of the conquest of the West which would link the vast continent into one healed whole. The idea of binding the sundered nation into one was a powerful one that gave the imperialistic Manifest Destiny a moral patina and provided an ethical impetus to the intrusion of the covered wagons into the vast plain. Simonsen stated that one of Gardner’s stereoscopic sets was titled “Westward, the Course of the Empire takes its Way,” a nod to the 1860 light-filled mural of the same name by Emmanuel Leutze located behind the western staircase of the House of Representatives. This aspirational mural, which was a naïvely optimistic view of American imperialism, can be considered a prelude to the post-war continuation a long-held dream, one once held by the photographer himself. Gardner, who had immigrated from the lowlands of Scotland, had first planned to settle in a cooperative community in Clayton County, Iowa, midwestern territory. Although he ultimately migrated to the East Coast instead, mentally, Gardner was not a stranger to the promise of the west, but the reality of Kansas was open and untouched country that was being marked by lines of iron, ur tracks on virgin sod. Without mountains, without mountains or hills, the endless flatness mirrored the featureless and open sky and seemed, to the European mind, to invite if not demand landmarks and sites of claiming. One could piously wish for new beginnings through renewal in a landscape unsullied by spilled blood, but the maddeningly flat expanse offered little of the uplifting grandeur that would be found further west. The drama of Gardner’s methodical record of his journey from St. Louis to San Francisco lies not so much in what we see today, but in what we know these photographs portend: the deliberate attempted extermination of wild animals and a free people in the name of commercial exploitation of a territory and its resources.

Alexander Gardner. Laying Tracks West (1867)

Thanks to his many contacts, Gardner had been hired by the Railway as an experienced professional documentary photographer to replace the amateur photographer William Bell, who subsequently published in 1870 an album of images, New Tracks in North America. A Journey of Travel and Adventure, using, without crediting, the work of Gardner on the project. The task of photographing on the plains was a daunting one: the wind blew constantly, whipping up clouds of dust which wreaked havoc with the fragile photographic equipment and the wet plates and interfered with the views, but Gardner’s images were far superior to those of Bell. It is quite possible that Gardner took his brief–to promote the westward movement of the railroad–quite literally, explaining the concentration on the impact of the Kansas Pacific on the 35th parallel. This was contested territory where one could meet with African Americans seeking a new life of freedom, displaced Native Americans being herded onto reservation lands, European immigrants desiring the open spaces of property that could be their own, and the Army that was to sort out all the corporate and private and governmental claims on the Empire, but Gardner kept his counsel. The Kansas Pacific Railway was originally intended to extend to San Francisco, Gardner’s destination, but stopped in Denver. Although the tracks themselves never reached their intended destination, Gardner followed the projected route, carefully recording the novel landscape and capturing the Native Americans as they existed on the edge of an extinction planned by the new occupiers.

The Next Post will discuss Gardner’s images of Native Americans.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.