Robert Mallet-Stevens (1885-1945)

The Architect of Art Deco, Part Two

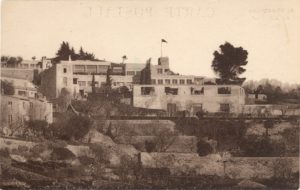

The semiotics of Robert Mallet-Stevens was completely different from those of the other modern architects, such as Mies van der Rohr. The radical modern architects were dedicated to building for the masses, providing affordable housing for them, buildings that, grouped together, became contemporary villages, prefabricated, assembled out of modules, they were meant to improve society as a whole. In contrast, the clients of Mallet-Stevens were avant-garde and wealthy and artistic and the villas he built for them were meant to display the elevated social position of the inhabitants. His architectural accomplishments were signs of privilege and elegance, shining in the sun, expansive in their display of distinction. Begun a year after the Villa Poiret at Mézy-sur-Seine, Yvelines, the Villa Noailles was started in 1924 at Hyères. the Vicomte and Vicomtesse de Noailles were close friends of Jean Cocteau and were the kind of owners excited to work with a cutting-edge architect who, not so incidentally, had no particular connections with socialism or Communism and no obvious desire to change the world. This large villa was also precisely situated on a hill with a magnificent view of the town below, stretching out towards the horizon. What is striking about both homes is their large and expansive size, the gardens that are enclosed within a structure where its grounds were carefully laid out in a grid pattern punctuated with lushly planted with trees and grass.

Villa Noailles in 1929 Photographe: Thérèse Bonney

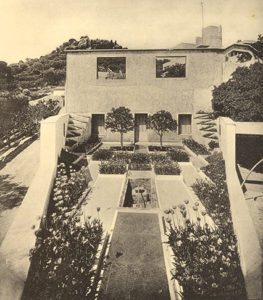

The most notable garden at Hyères, completed in 1928 was triangular cubist inspired design by Gabriel Guevrekian (1872-1970), who was one of the stars of the Paris Fair of 1925.

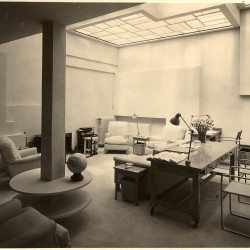

This villa is characterized by contrasting textures on the exterior slabs, some of which are rough and some are quite smooth in contrast. The Villa Noailles has expanses of blank unbroken walls, giving it a more closed in and shuttered look from the outside, keeping the openness of the interior spaces a secret. Inside, the architect was apparently unable to bear the blank wall and frequently used indents, created squared insets or niches to break up the flat expanse, causing long walls to be framed like cabinets. Robert Mallet-Stevens, also a set designer, had written an article “Le Cinéma et les arts: Architecture,” in 1925 explaining the idea of repetition in film. “Architecture plays,” he said, indicating that architecture had to be a “player” in the film by doubling the narrative or the reappearance of certain motifs throughout the film. In the movies, such reoccurrences were termed photogénie. It is clear that this idea of restating a theme was also the architect’s method of design–an eclectic and inclusive combining of modern art movements and modern architectural theories. For example, the ceilings are adorned with glass lit soffits with the De Stijl grids demarcating the light streaming down.

When he was asked in 1928 by the owner to make a film about the home, the repetition of obdurate cubic form inspired the photographer and sometime filmmaker, Man Ray (1890-1976). Ray, eying the tumbling squares, stilled by blank surfaces, thought of the famous poem by Stéphane Mallarmé, Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hazard of 1897, and reimagined that the poem with the die as a house. The idea of a thrown di, rolling across the landscape became the theme of his 1929 film Les Mystères du château du dé.

A Robert Mallet-Stevens interior was always more elaborated than one by Le Corbusier or by Gropius simply because there were more shapes, a multiplication of edges. An interior staircase allowed him to show off the zig-zag progression of the stairs rising up a straight ascent or, in a tight space, stairs could be tucked into a tight curve or folded into the side of a cone shape. The Villa Cavrois, a later work of 1932 of which more will be said later, had unique dining room furniture, a long wooden table, and many wooden chairs, resting on a parquet floor of zebra wood squares. The wall is broken with beams of zebra wood, reinforcing the theme of horizontal stripes, which fame a mural by his long-term collaborators the twin Martel brothers Jan and Joël. The commission for the Villa dated back to the Paris Fair of 1925 when the partnership of Robert Mallet-Stevens and the Martel Brothers came forcefully to the attention of the fairgoers when the concrete Cubist trees for the Garden of Modern Housing by Mallet-Stevens became the scandal of the event. The famous Cubist trees, designed by Robert Mallet-Stevens and executed by Jan and Joël Martel, were destroyed after the Fair was closed in October of 1925 and exist today only as maquettes.

Cubist Trees by Robert Mallet-Stevens and the Martel Brothers

Models wearing Sonia Terk-Delaunay Designs

The notorious Cubist trees were executed in concrete and sprouted from a garden was located next to the Pavillon for the twin cities of Roubaix and Tourcoing. Located on the Belgium border, a few miles from Dunkirk, and quite near Arras but dominated by Lille, these towns specialized in the manufacture of textiles. Roubaix was one of the first sites of French industry when in 1469 Charles the Bald gave Peter of Roubaix permission to manufacture cloth. Two centuries later, Charles the Fifth allowed the town to manufacture velvet, fustian, and linen for the common people. By the middle of the nineteenth century, Roubaix called the “Manchester of France” specialized in the spinning and weaving of wool and was the principal supplier of wool yarn for France. Like Roubaix, its twin, Tourcoing was the coveted site for the enemies of France and Belgium, being attacked and conquered by the English, the Austrians, the Dutch and the Saxons. This industrial town also specialized in wool manufacture but there was more of an emphasis on fine cloth and tapestries of mixed silks and mercerized or lustered cottons and “oriental type” carpets. Although today these towns have been deindustrialized, at the of time of the 1925 Fair, they were studded by smoking chimneys of the many factories.

Because both of these towns had been conquered by the Germans in the wake of the fall of Lille in October 1914, the presence of fabric manufacture at the Fair meant more than a mere presentation of the most recent textile manufacture. The area, the battleground of the Western Front would not be liberated until October 1918. Now fully recovered, the towns celebrated the end of a brutal occupation and their subsequent recovery. Designed by the Dutch architect Georges de Feure, the Pavilion for these twin towns was a small brick building, hexagonal in shape. De Feure copied the local architecture by selecting the local brick, which could be red, yellow, brown or cream as his building material. These native brick structures were traditionally capped with white accents blocks, that were used to underscore the shape of the roof or to accent windows and doors and call attention to the angles. The significance of de Feure’s presentation was its unalloyed regionalism. It is often assumed that the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes was strictly modern, but, despite its name, the sub-text of the event was its emphasis on the French provinces, upon the regions with their unique cultures. The building of brick from the Western Front not only echoed the local architecture of the region, decidedly historical and not modern but also emphasized the towns’ long affiliation with industrial arts and crafts. De Feure alluded to the many factories through the stacked entrance terminating in a chimney shape.

Georges de Feure. Pavillon of Roubaix and Tourcoing

Adjacent to this Pavillion was a long garden, complete with a cooling fountain. The fairgoers could rest on small wooden folding chairs under the dubious shade of sculptured trees. These concrete trees were the most prominent manifestation of Cubism at the Fair, where the administration was extremely conservative and tended to exercise censorship. Mallet-Stevens, a good friend of the painter Fernand Léger, installed one of his post-Cubist works in his Tourist Pavillon and was asked to remove the offending object from the wall. The architect refused and the painting stayed in the Pavillon. It is possible the grove of trees was a defiant answer to the would-be censors, but Mallet-Stevens frequently used the shattered forms of Analytical Cubism in his architecture. One need look no further than the protruding blades of the Tourist Pavillon or the layered coat rack at the Villa Noailles or his fractured lighting fixtures to see the prior use of intersecting shards. The height of each Arbre Cubiste in the garden was about twice human size, a scale made clear when Sonia Terk-Delaunay posed her models wearing the Cubist-inspired clothes she designed beneath the Trees around the fountain. As if it were a decade ago, cartoonists once again had their way with Cubism, signifying that the movement was still not understood or accepted. The attribution for the Trees has been muddied over time, sliding in favor or the Martel brothers, but, when one examines Mallet-Stevens, his architecture, his interior design and his product design, it becomes clear that the Trees were his invention. That said, the silly scandal of the Cubist trees led to an important commission in 1929 from Paul Cavrois, an industrialist from Roubaix.

Villa Cavrois showing use of yellow bricks

Cavrois owned an old textile firm, the Cavrois-Mahieu company, located in Roubaix, “the city of a thousand chimneys.” His five factories employed some seven hundred people and created high-end fabrics destined for the Parisian market. Cavrois, who had seven children, needed a large house for his family and decided against an abode in the traditional regional style. Perhaps he met Mallet-Stevens in Paris in 1925 and quite possibly may have watched the construction of six of his houses on a narrow dead end street in the sixteenth arrondissement, now called rue Robert Mallet-Stevens, completed in 1927. For whatever reason, the factory owner selected this well-known and proven architect of wealthy clients for the commission. The architect’s brief from Cavrois was “Abode for a large family. A home for a family living in 1934: air, light, work, sports, hygiene, comfort, economy.” The very large villa was built in the residential suburb of Beaumont and is covered completely in long yellow bricks—an alkaline color, imported from Belgium. These bricks, used without restraint over the entire surface, constituted a decorative motif, an external texture. Mallet-Stevens had a penchant for seizing upon building materials and turning the act of building and construction into décor. This willingness to respond to the environment was his trademark that made each of his architectural works site specific and also separated him Mallet-Stevens from the pure modernists. A comparison of the bricks used in the buildings in Roubaix and Tourcoing and those applied to the Villa Cavrois shows that the yellow bricks of the Villa are so long and narrow that they make a fabric or a facture, a surface rather than a pattern that embraced the entire house. The unrelieved stripes of yellow on the outside are echoed by stripped woods, ranging from light to dark tones inside. Planks of wood were used to border the walls and simple slabs constructed the made-to-order furniture.

Interior Design by Mallet-Stevens and the Martel Brothers

Like his colleagues, Mallet-Stevens refused to use any ornamentation but then he didn’t need to. He allowed the dance of light and shadows and the materials themselves to be the stars in their own right, allowing on art on the walls. The villa was one of the highlights of his career and became a metaphor for the decline of the reputation of the architect. Overshadowed by Le Corbusier, who knew how to publicize himself, Robert Mallet-Stevens died in obscurity and poverty in 1945, ordering his archives to be destroyed. The Villa Cavrois suffered equally. Occupied by the Germans in 1940, the home was purchased by a hostile and unsympathetic developer in the 1980s. The unscrupulous businessman stripped the home of its furniture, its exotic woods and even ripped out the plumbing–all sold–in a craven act of vandalism.

By the mid-1990s, the home was devastated seemingly beyond repair but famous architects intervened in a long campaign to save the home. In 2001, France purchased the home and began a 23 million euro restoration that took years. Much of the house had to be recreated completely from photographs, the only records of the building’s former attributes, and slowly some of the authentic materials have been found and bits and pieces of the unique furniture have been located and put back in place. As with the Bauhaus faculty houses for Klee and Kandinsky, the restorers re-discovered the original deep De Stijl colors used on the walls. The parquet flooring, 90% recovered and restored, was relaid by the very same Belgium firm that installed the floor in 1932. Meanwhile, in 2005, the reputation of Robert Mallet-Stevens was also restored with a long overdue restoration at the Centre Pompidou. The Centre des monuments nationaux reopened the home after fifteen years, its distinctive brickwork carefully reglazed. After a decade of careful building, a forgotten and insulted work of architecture that had become a ruin was transformed into a masterpiece again. Open today for pilgrims who now appreciate this remarkable architect of Art Deco, this home exemplifies what Mallet-Stevens once said, “Genuine luxury is living in a well-heated, well-ventilated, gay, and light-filled setting, requiring the least number of useless gestures and the smallest number of servants.”

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.