Defining Art Deco

The Meaning of “Moderne”

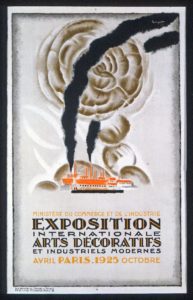

One should always beware of long titles, too many words usually conceal or reveal inner contradictions. Take, for example, the 1925 Paris International Exposition, the name of which is long and self-defeating: “Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes” or the International Exposition of Decorative and Industrial Arts, begging the question of whether the arts could be both decorative and international. Not until 1968 were all the adjectives swept away in favor of two signifying words “art deco” coined by the historian Bevis Hiller in his book Art Deco of the 20s and 30s. The fact that neither the exposition nor the impact of the numerous exhibitions was discussed at any length until 1968 indicates the uncertain relationship between the past, present, and future that existed on the Fairgrounds in 1925. Hiller was correct that a style he called “Art Deco” emerged and this style certainly indicated “modern,” but, in 1925, being modern was fraught with tensions. As Jared Goss explained in his book French Art Deco:

The narrative of French Art Deco was firmly established by the time of the 1925 Paris Exposition, formed in large part by the designers, museum professionals, and academics who had helped shape the style itself. In books and newspapers and magazine articles, they defined Art Deco’s characteristics and explained its philosophy, noting that it was distinct from manifestations of the movement in other countries by its embrace of its national past as the intellectual point of departure for creating something new. While designers elsewhere often rejected earlier aesthetics, materials, and manufacturing techniques. French designers sought innovation by embracing history. Specifically, the roots of French Art Deco are to be found in the ancien régime–the political and social system of France before the Revolution of 1789–and its time-honored traditions of apprenticeship and guild training. During the eighteenth century, France established itself in the forefront of the luxury trades, producing furniture, porcelain, glass, metalwork, and textiles (not to mention clothing, perfume, wines, and cuisine) of unsurpassed refinement and elegance. Indeed, Paris became what could be considered the style capital of the Western world.

Poster: “Exposition internationale des Arts Décoratifs et industriels modernes ” (1925)

This Exposition of 1925 was intended, by its founders, to restore or to reiterate the dominance of France in the applied arts and decorative design. Interestingly, this large event did not include the fine arts, France’s historical pride, but focused on showing how the nation still stood astride of the luxury trades. In stepping aside from the current avant-garde, especially Cubism, except as the handmaiden to applied art, Art Deco, like much of the visual culture in France between the wars, situated itself part of the larger cultural desire to stop time and to retour à l’ordre. The need to freeze any forward motion in the arts was coupled with an anxiety over the nation losing its dominance in the arts, especially the decorative arts, a concern that dated back to the pre-war era. The source of this worry was, of course, Germany, the perpetual enemy and rival to France. But by 1925, Germany was defeated, excluded, outlawed, and was not even invited to this Exposition until the last minute. The goal of the event was to assert the continued dominance of France in the decorative arts, which heretofore had been expressed only through fashion. In addition to establishing the authority of France in all things decorative, the characteristic of what precisely “French” stood for had been reduced to the classical or the timeless. Therefore, to be French in the art world, from fine arts to architecture, was to extend the historical styles into the twentieth century. Art Deco, as a modern style, was an applied version of late post-war conservative version of pre-war Cubism, which found a natural home in decoration. To the extent that Art Deco was modern, it was that this style was linked to all manner of objects which were, in turn, part of a growing consumer culture, an aspect of modernism that the French had virtually invented. The problems emerged with the term “industrial” or the machine age, which was linked to industrialization. On one hand, the idea of industrial design had to be reckoned with—Germany and the new Soviet Union were making strides in this new and modern area–but, on the other hand, France was reluctant to industrialize and would continue to resist that form of modernization well into the Vichy period of the Second World War.

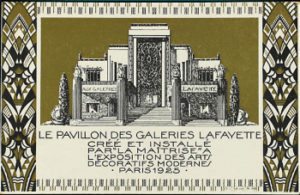

Pavilion of the Magasins des Galeries Lafayette, Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes, Paris 1925

Beau, Georges (1892-1958)

Dufrene, Maurice (1876-1955)

Hiriart, Joseph (1888-1946)

Tribout, Georges Henri (1884-1962)

In 1925, the Great War had been over for seven years and the European nations were slowly recovering from the ordeal. As English speaking and English writing people, we tend to hear more about the brief American Experience in this war and we are familiar with the British anti-war poetry and the legend of the well-born and the well-bred, the flower of English manhood dying on the battlefields of Flanders, alongside their colonial allies. But it was the French who suffered the most during the Great War. The battles were fought on French soil, on the border shared with the Belgians. German strategic plan for winning the war was to bleed France white, to fight the war until there were no French men left to block the way to Paris. The exsanguination tactic worked quite well—the French lost the most men of any nation—but Germany also bled itself in the effort, and, unsupported by allies, was forced to surrender. When one asks the question: why did the French surrender to the Germans in 1940, one has only to look at the statistics of loss to realize that the nation would have done anything to survive, gone to any lengths to save its new generation of young men, now so precious to its uncertain future. But in the 1920s in France, the future was unknown, Germany had been vanquished, and it was finally time to celebrate.

Joséphine Baker est une artiste emblématique des années folles, qui correspondent aux années 1920

But in the 1920s in France, the future was unknown, Germany had been vanquished, and it was finally time to celebrate. The années folles was the jazz age in Paris, the years of the new woman in France, the time of the Lost Generation, nomadic and unsettled, presided over by Gertrude Stein the expatriate American poet. Behind the fun was caution, for, despite its exuberance, the mood was conservative, regardless of the presence of modernity, the gaze was firmly fixed to the past. It is out of the odd paradox of post-war modernism and the retrospective mindset among the French that the glittering and commercial spectacle of the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris emerged in all its glitter and glory. Taking advantage of good weather, the Exhibition opened in April and closed in October, attracting thousands of visitors, most of whom were delighted with the expansion of commodities crafted in the name of all that was modern. However, there was the presence of the radically modern, represented by the Pavillon de l’Esprit Nouveau by Le Corbusier, tucked away behind the Grand Palais in obscurity, and the Soviet Pavillon by Konstantin Melnikov; and the modern that was precisely the opposite of radical. The other modern, which was later termed “moderne” an appellation of light mockery, or Modern Light, was exuberantly decorative and ostentatiously ornamental. That said it was the “Moderne” that dazzled and thrilled the crowds; it was the Moderne that cemented the French reputation for being the queen of the decorative arts, the arbiter of luxury goods, the seer of all things fashionable.

The 1925 Exhibition in Paris cemented Cubism as a style for applied art and was notable for its rejection of industrial design and modern architecture, despite its long and unwieldy name. Years passed, another War intervened, post-World War II aesthetic judgments rejected the decorative and rejoiced in the abstract. It was not until the 1960s, a decade beloved for its Youthquake styles, neon colors, curvilinear psychedelic designs and a new appreciation for the decorative, that this exhibition was revisited and renamed: ART DECO. By the 1960s and the definitive volume by Bevis Hiller, modern architecture had long since been winnowed out from its original surroundings and now reigned supreme as the International Style, while the prevailing style of the 1020s had slid into oblivion and disapproval. Since the sixties, Art Deco has been named and understood as an important style, which was not to be disparaged but was to be appreciated on its own terms which were part of its time, those few fragile years between the Wars. Like Germany, France has a housing shortage and, like Germany, the nation needed to modernize its infrastructure; but unlike Germany, Holland and even Russia, France decided to reject the future for an exploration of a contradiction in terms, a historicized modernism.

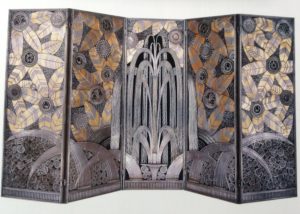

Exhibition Catalog with cover by Robert Bonfils

This modernity, like Baudelaire’s modernity of the 1860s, was expressed safely, through fashion and style. This modernity was drained of any threat and was safe and positive. Lacking any philosophical or theoretical underpinnings, Art Deco was, nevertheless expansive and inclusive and open-minded, accepting ancient Egypt and American culture, cashing in on the discovery of the tomb of King Tut’s Tomb in 1922 and turning the engineering triumph of an ocean liner into a decorative poster. Closer to home, Art Deco sampled the Wiener Werkstätte designers, especially Josef Hoffmann and Kolomon Moser, gave a nod to Russian Constructivism, and repurposed Cubism to its own ends , An accessible accumulative style of quotations and appropriation, Art Deco is perhaps best understood through the artists who represented it, not necessarily the fine artists—that would be the Cubists or the post-Cubists—but via the works of the decorative and applied artisans, the graphic artists, and the interior designers. As for the architects, the best examples of Art Déco architecture were in New York, but in Paris, some remarkable temporary buildings at the Fair, built for the French exhibits introduced the French stance on decorative and ornamental art to the rest of the world. The Fair was a frank and unapologetic trade fair for French merchandise, especially luxury goods and consumer goods of great style and the undeniable Gallic flair for the chic. Art Deco, in its eclectic way, signified “modern” and in doing so also signaled that old styles were now outmoded. This signal educated the potential buyer as to what to purchase next. The most succinct description of current trends was made by the painter, Charles Dufresne, who explained the difference twenty-five years had made to French design: “L’art de 1900 fut l’art du domaine de la fantaisie, celui de 1925 est du domaine de la raison.” Indeed, the Fair marked the low point and eclipse for Art Nouveau and the advertisement of Art Deco, the new synthetic style of applied art, was marked, not by nature but by the machine.

General View of Exhibition Pavilions

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.