THE CONSTRUCTION OF INFORMATION

The PhotoEssay in the Weimar Republic

In 1919 Austrian artist Raoul Haussmann (1886-1971) found an image in the Berlin Illustrated News (Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung), a seemingly innocuous photographic portrait of the defense minister (Reichswehrminister) of the newly formed Weimar Republic, Gustav Noske. The Noske photograph, a man in a suit seated in an ordinary chair, became the placeholder for Haussmann’s Dada interventions. The head was removed and replaced with an assemblage of machine parts and the torso, the shirt front, was cut away and replaced by an anatomical illustration of the human lungs, covered in brachial tubes circulating air. Noske, himself, was a particularly unsavory character, certainly deserved the dismemberment. On the surface, he was ordinary enough, a man who could vanish into a crowd, anonymous. The jowls of Noske were drooping, his wavy hairline receding, his uninteresting face distinguished by a small short mustache, like the one Hitler grew, and a pair of round spectacles. In other words, his was a face tailor-made for the Dada artist to photomontage into mechanical oblivion.

Gustav Noske (1868-1946)

But Noske was also an excellent target for Haussmann who, like his colleagues was left wing and sympathetic to the causes of socialism and communism. Noske was a member of the Social Democratic Party, the party in power, and he protected the newly formed Republic from an outbreak of rebellions in January of 1919. This month, barely two months after the Armistice was signed was one of unrest, food shortages, deflating currency, lack of food and fuel, and a lively two-day meeting of the Communist Party of Germany ended. But the match that lit the streets on fire was the refusal of the Berlin police chief to resign. His supporters sprang to his defense and the Spartacist Group, rose up to oust the recalcitrant leader of the police. Arising against the government like Spartacus led the slave revolt, battling the Roman Empire, the Spartacist movement, led by Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, was a workers’ party, dedicated to installing a Russian style revolution in Germany. Starting on January 5th, Bloody Week gravely threatening the future of the Republic and events spiraled out of control. The revolutionaries could not agree as to what to do next, and the government called for volunteer army veterans to defend it. The President of the Republic, Friedrich Ebert, ordered the revolt to be put down and Noske was able to organize a paramilitary right-wing organization called the Freikorps, more soldiers, to quell the unrest in the streets. It is important to note that the Army itself never surrendered, only the German government signed the relevant documents, and, as a result, the military was no friend to the government. In fact, there were mutinies at the sea ports, and sailors and soldiers were a free-ranging danger that also needed to be dealt with. However, the Freikorps was eager and willing to fight for whatever cause or reason that gave it the opportunity to display aggression, and it went about its business with efficient brutality.

Raoul Haussman. Self-Portrait of the Dadasoph (1920)

The leader of the Freikorps was none other than Gustav Noske. Noske installed searchlights and swept the streets of Berlin at night, searching out anyone violating his curfew. Armed with military equipment, field guns, howitzers, machine guns, hand grenades, and trench mortars, the Freikorps retook the buildings seized by the Spartacists and their worker allies, mowed down street demonstrators, ending the Week with the blood that gave the days of rage their definitive name. Noske gave his demobilized “soldiers” equipment for hand-to-hand fighting and positioned his regiments to turn machine guns the protesters on Linden Boulevard. For a left wing inclined artist, such as Haussmann, the defense minister was a particularly unpleasant character–willing to deploy thugs to quash a peoples’ rebellion. By January 13th, the Spartacists and their leaders are in hiding. But the Freikorps tracked down Liebknecht and Luxemburg and dragged them back to the authorities. Somehow they were both murdered. The body of Liebknecht was “delivered” to the morgue with bullet holes in is forehead, and, five months later, the body of Luxemburg surfaced from the Landwehr Canal, where it had been dumped. On the 24th, a public funeral was held for the leaders and the nearly forty other members of the Group. The government moved to Weimar, out of reach of any further uprisings. This horrible ending to a doomed uprising would not be forgotten, either by militant nationalists, like the Freikorps, which would soon be replaced by the Nazis, or the vanquished, the German Communists. The days of Noske were numbered. After another uprising a year later in March of 1920, the Kapp Putsch, the defense minister was removed from power.

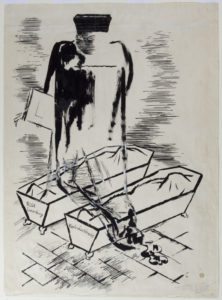

George Grosz. In Memory of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht (1919)

In the midst of street protests, the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung or BIZ, as it was known, continued to publish, just as it had since 1892. The publication was the first to inform its readers of current events, not through words, but through pictures, creating the photo-essay. The photo-essay became the standard means of conveying the news to the general public which might want an easier and more legible way to keep up with events, without plowing through rows of gray print, marching up and down tall newspaper pages. The layout was unique for the time, combining photographs and a text which explained the images, foregrounding the picture and its entertainment value over an in-depth study of current events. The editor during the 1920s, Kurt Korff, stated that “Life has become more hectic and the individual has become less prepared to peruse a newspaper in leisurely reflection. Accordingly, it has become necessary to find a keener and more succinct form of pictorial representation that has an effect on readers even if they just skim through the pages. The public has become more and more used to taking in world events through pictures rather than words.”

Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung layout

BIZ remained apolitical, a wise course during the Weimar Republic, but its appearance of normal times in the midst of political and quasi-military demonstrations laid it open to critique. The power of these periodicals–and by the 1920s most of the large German cities had an illustrated news publication during the Weimar Republic–was enormous. The illustrated news outlets were accessible and omnipresent and read by everyone in Germany. This media proved to be a bonanza for German photographers who suddenly had an outlet for work as photojournalists. In the late twenties, Erich Salomon concealed his Ermanox and photographed diplomats conferring and trials deliberating. Felix Man showed a typical day in the life of an up and coming dictator, Benito Mussolini. In his book, The Photography of Crisis: The Photo Essays of Weimar Germany, Daniel H. Magilow noted that the combination of photos and text was not necessarily new in the 1920s but these publications “used photographs in new ways–in novel essayistic forms that did more than just illustrate the text. As sites of political debate changed, so too did the forms in which those struggles unfolded.” The photo essay was, Magilow asserted, characterized by “the sequencing or arrangements of photographs to tell stories, make arguments, communicate ideas, elicit narratives, evoke allegories, and persuade listeners to accept new ways of seeing and thinking had accompanied the medium since its origins in the early nineteenth century.” The photo-essay took a novelistic approach, and, in doing so, assumed a power over the story and over the images, turning the photographs from unique images to “film stills” in the service of the words. Like a mini-novel or short story, the photo essays followed a traditional structure of beginning, middle, and end, or beginning, crisis, and resolution. Life does not wrap itself up in such a neat and convenient fashion and the dramatic format, driven by the need to entertain the reader and to retain her attention could shape the “news” in profound ways.

Raoul Haussmann. Dada Siegt (1920)

This new power for the mass media meant that, for the Dada artists who used photomontage, the illustrated news magazines were ripe targets. The carefully non-political stance during the Weimar Republic maintained by the publications would have been difficult, perhaps shifting the slant, or the kind of stories published, towards the conventional or status quo outcome, while skipping over the unsavory aspects of a Republic under siege by crosswinds. That said, the Dada artists and the illustrated news magazines shared something in common: they both lived in the present, or a mental and cultural phenomenon called “presentism” by Maria Stavrinaki in her book, Dada Presentism: An Essay on Art and History. She quoted Raoul Haussmann saying, “The Dada person recognizes no past which might tie him down. He is held up by the living present, by his existence.” Being published daily, the news magazine, such as BIZ, had to make the most of the present, today. The people of Germany were also forced to live in the present: the past was one one of shame and defeat, the present was unpleasant and uncertain, and the future seemed grim. There was nothing to look back to and little reason to ahead into the future. There was only the present. The Dada artists, reveling in the moment, lacking any interest in making “universal” art or art that would appeal to the ages, pounced upon the pages of BIZ with their scissors and razor blades. Tearing into the neatly arranged layouts, disrupting the flow of the story, removing characters from the novel, excising certain words and phrases, the Dada artists, especially the leading photomontage engineers, Hannah Höch and Raoul Haussmann, dismembered the plot lines as succinctly as a surgeon would carve into a body.

Hannah Höch. Cut with the Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany (1920)

Dada collages or photomontages are usually assumed to be meaningless or random, but, if as Stavrinaki stated, they are evidence of “presentism” then each melange has a meaning or multiple meanings. True, unlike its arch enemy, the photo-essay, the photomontage has no center or unity or organization, but its copious surplus does not indicate that absence of meaning. Those scholars, who have painstakingly investigated the images used and the words cut out, have uncovered meanings, plural. Hannah Höch, in a neat twist, actually worked for the Ullstein Press, a publishing empire that owned BIZ, and collected photographs from her employer, using them for her photomontages. In The Visual Arts in Germany 1890-1937: Utopia and Despair, Shearer West wrote that “Cut with the Kitchen Knife is replete with references to both Wilhelmine Society and Weimar culture, and it includes hundreds of photographs carefully juxtaposed for ironic or satirical effect. To make her satire most effective, Höch included mechanical illustrations, architecture, words cut out from newspapers, animals and photographs of over 50 individuals, many of them recognizable. The odd title of the work outlines its agenda. Höch chose the image of a “kitchen knife” as a way of giving herself, as a woman, the power to expose the male-dominated society of Weimar Germany. She metaphorically used a domestic implement to cut open the ‘beer belly culture’ of Weimar. Beer, both a German drink and an integral part of male society, was chosen as a way of emphasizing the bloated and heavy quality of German militarism; the word ‘culture’ (Kultur) is used in its fullest sense to indicate the society’s whole artistic, political, and educational profile.” West gave a partial list of what was a cast of thousands, divided into “Dada” and “anti-Dada” sections that included Ebert, Hindenberg, Noske, Wilhelm II, Crown Prince William of Prussia, and Haussmann, Grosz, Baader Herzfelde, and herself, also bringing in Marx and Lenin.

Vast, on its own terms, this impressive photomontage dwarfed those of her male counterparts, but its debut in 1920 at the Dada Messe in Berlin was its last appearance for decades. Höch, in her own time, was not considered significant to the movement (she was a woman) and had so little importance in the mind of Richard Huelsenbeck (1892-1974) that he failed to include her in his book on Dada. He declared Dada in Berlin to be “dead” in 1920, and Höch drifted away from the non-movement. Cut with the Kitchen Knife, over-sized and fragile, was kept in her studio, while she showed more up to date photo-collages, in other words, their content was timely and contemporary to the exhibition in question. For her, Cut with the Kitchen Knife was not of the “present.” In Objects as History in Twentieth-century German Art: Beckmann to Beuys, Peter Chametzky wrote of all the exhibitions in which she participated. She sent the photomontage, Cut with the Kitchen Knife, to none of them. As Chametzky said, “Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada’s close association with Berlin Dada may have made Höch see it as dated.” By 1961, Chametzky reported, after the photomontage was purchased by the Berlin National Gallery, “she feared people would not spend enough time looking at it or know enough about Berlin in 1919-20 and Berlin Dada’s mission to appreciate its complex references and technique.” It seems clear that the Dada montages were making deliberate political statements about the now, and that their destructive techniques–cutting, disrupting, destroying continuity and flow–were deliberate counter-measures, designed to undercut their sources, the illustrated mass media. As revolutionaries, the Berlin Dada attacked the present, tearing its smug stories into pieces and re-presenting the carefully chosen images and selected words in chaotic anti-compositions without centers. If we accept Richard Huelsenbeck’s claim in his 1920 book, The History of Dadaism, that the movement ended with his book, then Dada in Berlin was part of one of the worst years in the history of Weimar Republic. The photomontages were, in their own way, a form of “news,” always new, always pertinent, but never laid out in easy linear narratives. Parasitic upon the enemy host, illustrated news, the Berlin photomontages robbed photo essays of their claims to truth and exposed the existing turmoil of the real world by a strategy of invade and disarrange.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.