Portraiture Reborn

George Grosz as “Hanswurst”

Even thought Dada dissolved in Berlin and the Dada perpetrators went their separate ways, one of the former members, George Grosz (1893-1959) never lost his disgust for Germany and for the German people. His art and his autobiography indicate little joy or satisfaction in his post-war life. Grosz did not celebrate his good fortune at surviving the Great War intact and unharmed, instead, he railed against those who profited from going to war–the industrialists–and those who supported the drive to conflict–the clergy and the press–without considering the ramifications. Grosz turned his baleful eye towards to German people who had blindly stumbled into a disaster that destroyed their honor. A left-wing artists, he considered Germans ugly, fat and stupid, turning away from the very real social issues confronting the Weimar Republic and giving in to the decadent pleasures made possible by a relaxing of Wilhemine restrictions. The targets of George Grosz are the “ordinary Germans,” the average bourgeois man, who is more likely than not to be involved in some kind of nefarious business deal, and his female companions, usually the lowest of prostitutes. Both are carriers of corruption and are metaphors for the internal rot within the German heart.

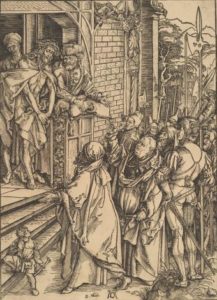

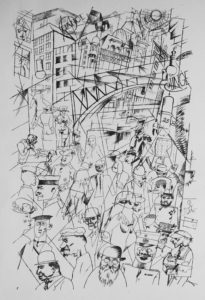

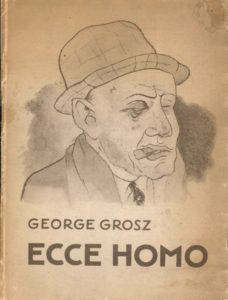

Nowhere does his horror for the sights and scenes he witnessed on the streets of Berlin rise to the fore than in George Grosz’s masterwork, Ecce Homo. This scathing series of eighty-four prints in color and in black and white was published by Malik-Verlag in 1923. The press founded by Grosz and John Heartfield became the target for more than one lawsuit over the merciless art of Grosz, who, along with Heartfield were the two most single-minded and remorseless critics of the pretensions of the Weimar Republic. Ecce Homo left no pillar of German society untouched; in the eyes of Grosz all were guilty and all were implicated in the ugly war and its aftermath. From its earliest days, the Weimar Republic had grappled with revolutions, a political coup, economic upheaval, dissident complaints on the left and right, and was, therefore, short tempered when it came to disturbing the peace. And George Grosz was a deliberate disturber and a serial disturber. The prints had short descriptions–two or three words–indicating that Grosz was speaking to an audience of fellow Germans, probably Berliners, who would recognize his “types” of immoral humanity, as the people they passed on the streets. The title, Ecce Homo, suggested a Biblical seriousness to the collection of prints, with a reference to the Suffering Christ, dragged before Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea, beaten and whipped and publically humiliated, crowned with a circle of mocking thorns. Thus, the question is raised–who is the Christ that is referred to? It is known that the phrase “ecce homo” means “Behold, the man!” both words and a gesture from Pilate, who appealed to the mob baying for a death. It is unclear, however, what Pilate meant. Was he mocking the would-be god who suffered like a mortal human or was he pleading with the crowd to show some pity and some mercy towards a harmless misguided country boy who had come to the big city with outsized ideas? Historically speaking, it is unlikely such a drama took place, for the Roman Empire routinely crucified any subject who, in any way, threatened its power. The Empire ruled through terror and terror is not effective unless it is complete and sweeps up all in its path, from major political opposition to minor Jewish men claiming to be a “son of God.”

Albrecht Dürer. Ecce Homo: The Presentation of Christ (1498)

The meaning of Ecce Homo in the work of George Grosz was more than likely related, not to the Bible, but to Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), whose autobiography was titled Ecce Homo. Neither Nietzsche nor Grosz takes the role of Pilate, and, under Nietzsche, for whom God is dead, the idea of “behold, the man” shifted from a man who is suffering to a man who disrupted the status quo. In section 25 of The Gay Science, Nietzsche wrote with his characteristic exaggerations and flourishes,

Have you not heard of that madman who lit a lantern in the bright morning hours, ran to the market place, and cried incessantly, “I seek God! I seek God!”… “Whither is God?” he cried. “I shall tell you. We have killed him – you and I. All of us are his murderers.”.. “ God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him.”

Nietzsche and his nihilism inspired the Dada artists in Zurich and in Berlin to accept a wartime loss of faith and hope. But Nietzsche himself regarded the realization that God was dead, except in the minds of traditionalists, could be liberating. The individual had no purpose, no reason for being: he or she simply exists without teleology or direction. No longer living for a “greater good,” the person is both innocent and liberated, beholding to no values and owning no morals, except those that one chooses to accept or to create. In other words, the philosopher embraced life, a life freed from belief systems that had once constructed and constrained it. Nietzsche rejected all that was morbid or obsessed with death and suffering and embraced the spirit of joy or Dionysus, the emotional and the alternative to reason. According to Ray Furness in his introduction to Nietzsche’s three works, Twilight of the Idols with the Antichrist and Ecce Homo, Ecce Homo was written in three weeks in 1888. In effect, the philosopher is saying “look at me” “behold” and claims to be the fool whose carnivalesque literary antics disrupt the foundations of German culture and philosophical reason. Nietzsche is some kind of holy fool, who refuses to be a saint or someone who thoughtless goes along with the received wisdom and adds to the blinding of society to its true nature. He is an outsider, a jester, and the fool, suggesting that these performers and certain child-like figures are the truth tellers of society. There is an inversion in Nietzsche that harkens back to Ecce Homo, suggesting that the powerless have the power of revelation and that the powerful can never reveal and are, therefore, powerless.

When George Grosz decided to do a series of prints, he was not only taking advantage of modern mass media and the possibilities of wide distribution he was also following the tradition of printmaking that was quintessentially German. Borrowing from Durer and Schongauer and even from his immediate predecessors, the Expressionists from Dresden, Grosz found the medium of printmaking to be an answer to the religious images of the Renaissance artists and the hopeful hedonism of the young Die Brücke artists. In an interesting presentation for the Tate Museum in 2010, Christine Battersby wrote “The Sublime Object ‘Behold the Buffon:’ Dada, Nietzsche’s Ecce Homo and the Sublime.” The “buffoon” she referred to is a character from German theater, not the high or artistic theater but the Teutonic equivalent of vaudeville. This character was named “Hanswurst,” a low peasant character, a Medieval buffoon, named after a sausage. In her article, “Fools Festooned with Foods,” Henriette Kassay-Schuster wrote that Hanswurst was the counterpart to Pickelhering come from the carnival culture. The Sausage, freely eaten before Lent must give way to the Herring during the season of waiting and fasting. Thus sausage and herring were “typical carnival foods” and were on the “side of excess and pleasure.” Hanswurst possessed a “Bakhtinian grotesque body” and embodiment of the “temptations of the flesh.” “Hanswurst manifests in the emergent seventeenth-century professional German theater as a specific German adaptation of Italian performance traditions, channeled through the theater style of the professional commedia dell’arte ensembles.” As Kassay-Schuster pointed out in the 2016 book, Food and Theatre on the World Stage, “Hanswurst” is a combination of a first name and a cheap and common food, and that “obscenities (both verbal and physical), acrobatics, physical comedy, and musical interludes” were the key ingredients that made improvisational comedy of this character so popular in presenting “man as animal.”

By the eighteenth century, “Hanswurst” “gained a very specific profile..As he is largely known today, in his brightly colored peasant clothing consisting of the trademark baggy yellow trousers, red suspenders, red jacket, and pointy green hat, offset by a white ruff, a broad leather belt, and the signature wooden sword.” It was the Austrian performers who pioneered the character and passed the buffoon on to the German culture, which also had a fifteenth-century folk tradition of the “Hanswurst” caricature that made the Austrian theatrical creation familiar and easy to assimilate. One hundred years later, Nietzsche wrote in Ecce Homo: “I have a terrible fear that one day I will be pronounced holy. I do not want to be a holy man; sooner even a buffoon (Hanswurst).–Perhaps I am a buffoon.” In his book, No Hamlets: German Shakespeare from Friedrich Nietzsche to Carl Schmitt, Andreas Höfele suggested that the buffoon is a role, played by both Hamlet and Nietzsche as a sort of disguise, concealing their ultimate goals. Hanswurst and suffering are combined with cynicism. Höfele noted that Nietzsche wrote that Ecce Homo was a kind of “cynicism that will make history.”

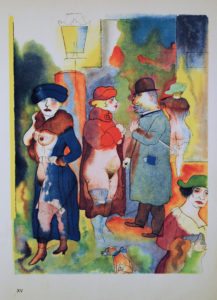

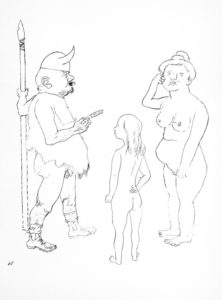

George Grosz. “In Memory of Richard Wagner.” Ecce Homo (1923)

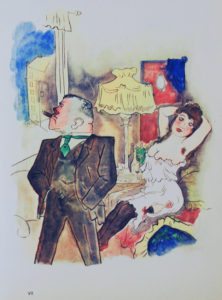

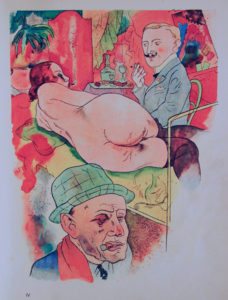

As Battersby noted, “Hanswurst was a licensed fool who spoke ironically and openly about contemporary affairs.” George Grosz, she stated, “positions himself as a Hanswurst and a counter to the wounded Christ.” In the series of prints, Grosz referred directly to Nietzsche twice, in the Plate “Dämmerung” (Twilight) and to their shared hatred of Wagnerian nationalism and German militarism in the Plate “In Memory of Richard Wagner.” Battersby called “Grosz’s portfolio” “a vicious satire on Germany society, German militarism, and the hypocrisy (especially the sexually driven duplicity) that was acted out on the city streets of Berlin during these years.” She quoted Grosz himself as saying, “All moral codes were abandoned.” Towards the end of her article, which is reprinted as a condensation on the website of the Tate Museum, Battersby remarked that Grosz did not share the affirmation of life that enlivened Nietzsche and his exuberant prose. Instead when he viewed the people of the streets and their public lives, Grosz asked, “What do I see?…only unkempt, fat, deformed, incredibly ugly men and (above all) women, degenerate creatures (although a fat, red, plump, lazy man is here considered to be a ‘stately gentleman’), with bad juices (from beer) and hips that are too fat and short…”

George Grosz. “Dämmerung” (Twilight) Ecce Homo (1923)

Grosz was making art at a very different time in German life–after a humiliating defeat. But the state of German society was far worse than a mere military defeat. Also defeated, as I pointed out in earlier posts, was German Kultur, their sense of identity, of being special, of having a mission born of ethnic superiority. Kultur was discredited and lay in ruins and ashes, like the battlefields where it died. Left without moral and ethnic guides, the Germans acted out, abandoning, as Grosz observed, their Kultur. The 1972 film, Cabaret, based upon Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin Stories (Goodbye to Berlin and Mr. Norris Changes Trains) (1945), the main character, Sally Bowles, an American expatriate adrift in Berlin, sang, “Life is a cabaret, my friend, life is a cabaret.” The director and choreographer, Bob Fosse, studied George Grosz and Otto Dix for their iconic images, raided their art and inserted their portraits and their colors into the scenes in the “Kit Kat Klub,” surely a play on KKK. The cabaret is the theatrical version of the carnival, a season in the year when society is given permission to relax and give free rein to their deviant impulses. Those days are a period of inversion: the high are brought low through satire and the low are elevated as the fools and the jesters who are given official and customary permission to speak out about the injustices in society and to point out the faults of the rulers. One of the great scenes in Cabaret is a spontaneous gesture from Joel Gray, the Oscar-winning “Master of Ceremonies,” who was referring a female mud-wrestling contest at the cabaret. The actor dipped into the mud and fittingly swiped his upper lip with mud, mocking Hitler’s mustache, a gesture allowed, briefly, at the lawless domain of the cabaret, the carnival. It is no accident that Adolf Hitler swept through Berlin with a fascistic and authoritarian broom, wiping away all of the establishments where the carnival was in full swing.

But in 1923, Ecce Homo is an illustrated guide to what was an inverted social system, where the war profiteer and the prostitute, the immoral survivors climbed triumphantly from the wreckage. Grosz depicted himself on the cover, suggestively turning his fedora into the hat of the holy fool or the buffoon “Hanswurst’s “pointy green hat.” In a color print featuring Grosz as the disgusted observer, the green is made clear. From his vantage point as the Dada artist who recoiled from his fellow Germans, George Grosz paradoxically produced the definitive group portrait of the Weimar Republic. As he himself wrote of the Republic, “All this had to end with an awful crash. It was a completely negative world, with gaily colored froth on top that many people mistook for the true, the happy Germany before the eruption of the new barbarism. Foreigners who visited us at that time were easily fooled by the apparent light-hearted, whirring fun on the surface, by the nightlife and the so-called freedom and flowering of the arts. But that was really nothing more than froth. Right under that short-lived, lively surface of the shimmering swamp were fratricide and general discord, and regiments were being formed for the final reckoning. Germany seemed to be splitting into two parts that hated each other, as in the saga of the Nibelungs. And we knew all that; or at least we had forebodings.”

The Weimar Republic dragged Grosz into court, accusing him of defaming the German military and of distributing pornography. Although certain plates were destroyed, Grosz and Malik Verlag were eventually acquitted. By 1932, an ascendant Hitler and the Nazis had already taken notice of the acerbic qualities of the artist and, being an excellent observer of his fellow human beings, George Grosz took his family and they all left for America, where he would be teaching at the Art Students’ League in New York City. Grosz would not return to his native Germany until 1959, where he died five weeks later.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.